Advocates are warning Manitoba’s most vulnerable children are being failed by a system meant to protect them – failures they say have been laid bare by recent deaths in the province.

The last time Natalie Anderson said she saw Xavia Butler alive was when she was nine-months old.

“Her eyes used to smile when she was with me. She knew what love was. She was very loved,” Anderson told CTV News in an interview last week.

Anderson said she raised Xavia from birth for the first nine months of her life through an informal kinship agreement with the baby’s biological mother.

“She was a beautiful, innocent, amazing child. She was very smart,” Anderson said.

Natalie Anderson with Xavia in an undated photo. Uploaded Nov. 1, 2024. (Natalie Anderson/Facebook)

Natalie Anderson with Xavia in an undated photo. Uploaded Nov. 1, 2024. (Natalie Anderson/Facebook)

Butler’s remains were discovered in a barn near Gypsumville this summer. Manitoba RCMP are investigating her death as a homicide, but told CTV News there was no CFS involvement in her case at the time of her death. They would not comment further.

Xavia’s death is one of several recent child deaths in the province raising alarms.

“In Manitoba, it’s every child matters unless you’re in Manitoba foster care,” said Brittany Bannerman, a foster parent with the Manitoba Foster Parent Association.

Bannerman has been calling for change in the child and family services (CFS) system – a system with nearly 9,000 children in care as of last year, 91 per cent of whom are Indigenous.

“We are watching kids that are facing trauma, that are the most vulnerable children and some of the most vulnerable people in our province be failed over and over again,” she said.

Those failures laid bare by recent deaths, she said, like that of six-year-old Johnson Redhead, a boy with complex needs who died after wandering away from his school in Shamattawa.

Or the death of 17-year-old Myah-Lee Gratton, who was killed despite her mother telling CTV News she had warned a child welfare agency the home she was in was unsafe.

“Until we deal with systemically the changes all around, it’s not going to get better,” Bannerman said.

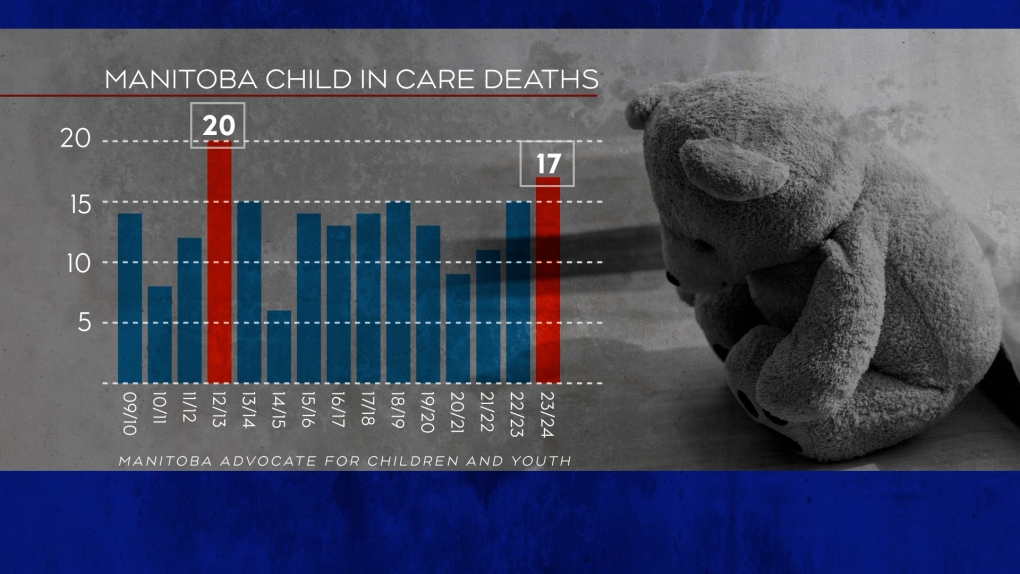

Manitoba sees highest number of deaths in care since 2012: advocate

This all comes as Manitoba saw the highest number of deaths of children in care in more than a decade. Manitoba’s Advocate for Children and Youth (MACY) said in 2023/24, it was notified of 17 deaths of children in CFS care.

(Graphic source: CTV News Winnipeg)

(Graphic source: CTV News Winnipeg)

MACY would not share the manner of death in these cases, citing confidentiality.

“The death of any child is devastating, and it speaks to the lack of support and resources in the system,” Advocate Sherry Gott told CTV News.

In its annual report, MACY notes that when caregivers don’t have access to the support they need, children’s safety can be compromised. Gott said heavy caseloads for social workers are adding to the problem.

“Government needs to step up and provide those resources for those children and those families.”

Case workers overwhelmed, some dealing with 50 cases: union

CFS caseloads are overwhelming social workers, Kyle Ross, president of the Manitoba Government and General Employees’ Union, told CTV News.

“They’re way overworked, and they’re fearful something awful could happen,” he said.

More than a decade ago, the final inquiry report examining the death of Phoenix Sinclair called for a ratio of 20 cases per social worker. The MGEU, which represents around 1,500 CFS social workers throughout the province, said that isn’t always happening.

“I know in some areas, the case loads are as high as 50,” said Ross, pointing to a shortage of workers in the system. “We hear overwhelmingly that they’re overworked. Their caseloads are too high. That it’s hard to keep up.”

Those concerns are shared by Shelley Baker, an on-call dispatch worker with Winnipeg CFS and president of CUPE Local 2153, which represents Winnipeg CFS support workers.

Shelley Baker, an on-call dispatch worker with Winnipeg CFS and president of CUPE Local 2153, speaks with CTV News on Nov. 6, 2024. (Source: Danton Unger/CTV News Winnipeg)

Shelley Baker, an on-call dispatch worker with Winnipeg CFS and president of CUPE Local 2153, speaks with CTV News on Nov. 6, 2024. (Source: Danton Unger/CTV News Winnipeg)

“Our system struggles,” she said. “Individuals that come into care have been traumatized in many ways, and we can’t always meet those higher needs and supports that are required due to the low ratio of staffing.”

She said since 2020, the average number of staff dropped from around 600 to just over 300.

“The massive overtime causes eventually burnout of those staff that are in place, and a lot of them are looking for other work,” she said.

Ross said workers he’s spoken with fear if something doesn’t change, something will slip through the cracks.

‘$22 a day isn’t paying the bills’: Manitoba has among lowest rates for foster parents in Canada: association

It’s not just the social workers feeling the strain. Jamie Pfau, president of the Manitoba Foster Parent Association, said underfunding is leading to a lack of foster homes.

As of last year, there were 6,314 children in foster homes in Manitoba, with another 2,186 children in other placements such as places of safety or staying out-of-province.

The province doesn’t track the number of licensed foster homes in the child welfare system, telling CTV News each individual agency is in charge of licensing foster homes.

“We’re seeing a huge turnover of foster parents, not only for the lack of funding, but it becomes very overwhelmed,” she said.

Jamie Pfau is the president of the Manitoba Foster Parent Association. (Source: Danton Unger/CTV News Winnipeg)

Jamie Pfau is the president of the Manitoba Foster Parent Association. (Source: Danton Unger/CTV News Winnipeg)

She pointed to a 2019 Auditor’s General report that found Manitoba provides the second-lowest basic maintenance rate for children in care.

The rate, according to the report, ranges from $22.11 to $32.50 a day—noting the rate hasn’t changed since 2012.

“The cost of living is so much more expensive. And, yeah, we haven’t had a raise in over a decade just for the basic maintenance,” she said. “$22 a day isn’t paying the bills.”

The auditor general had recommended the province’s Department of Families promptly and regularly review the basic rate to make sure it covers the costs incurred by foster parents.

A follow-up report published last year said the department was working on this recommendation. However, when asked about this, Manitoba’s Families Minister Nahanni Fontaine wouldn’t say if the province has or would be reviewing or updating the basic maintenance rate.

“The department funds child welfare to the tune of $420 million, and those dollars are allocated to (the authorities), which then disseminate it to the CFS agencies,” Fontaine told CTV News, adding her department is working to ensure that foster parents get the supports that they need.

‘Child welfare is going to look very, very different’: families minister says changes on the way

Fontaine said her department is making changes to the way child welfare is done in Manitoba.

On Oct. 1, the province made amendments to the Child and Family Services Act to allow customary and kinship care agreements. Fontaine said this is the most important thing her department is doing.

Customary and kinship care agreements will allow children to stay with a family member rather than be apprehended into the CFS system, Fontaine said, while still providing the family member with supports for care and ensuring biological parents don’t lose their parental rights.

“What you’re seeing then is you’re seeing more children staying with their families or in their communities, which goes a long way,” she said, adding this will help reduce caseloads and the number of children in foster care.

Manitoba Families Minister Nahanni Fontaine speaks with CTV News Winnipeg from her office in the Manitoba Legislature on Nov. 7, 2024. (Source: Danton Unger/CTV News Winnipeg)

Manitoba Families Minister Nahanni Fontaine speaks with CTV News Winnipeg from her office in the Manitoba Legislature on Nov. 7, 2024. (Source: Danton Unger/CTV News Winnipeg)

On Thursday, the province also made changes to Manitoba’s Child and Family Services Act with Bill 38—an amendment recognizing and giving more authority to Indigenous jurisdictions.

This includes transitioning Indigenous children and families with Manitoba CFS services to Indigenous service provinces. This also allows Indigenous service providers to become judge-appointed guardians of an Indigenous child, apply for a child’s birth certificate, and investigate reports of a child needing protection.

“Child welfare is going to look very, very different in the next couple of years,” Fontaine said.

-with files from CTV’s Will Reimer