Clifford Jack Widdicombe was one of the most grounded people you were ever likely to meet.

Known as Jack, Widdicombe was born May 2, 1921, on his family’s farm near the town of Foxwarren and spent the majority of his life there. He took over the family farm soon after the Second World War and, in 1947, married his high school sweetheart, Florence Peterson, with whom he raised three children, Melva, Daryl and Penny.

He became well-known in the community thanks in large part to his willingness to help others. He operated the local snowplow for several winters, coached and refereed minor hockey for many seasons and served on the board of the Manitoba Pool Elevators.

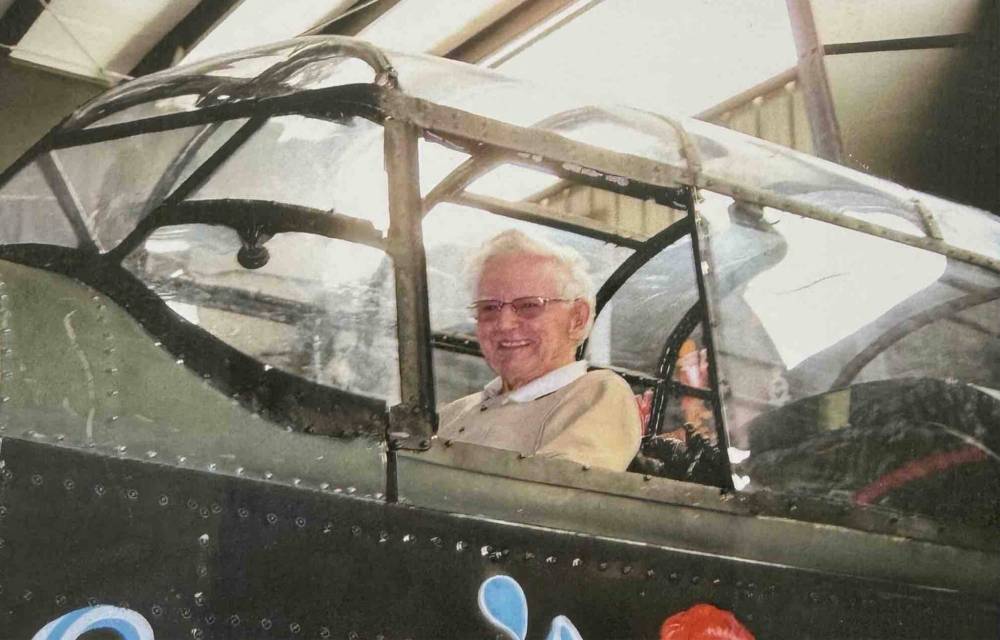

Brandon Sun files

With pilot Peter Moodie (right) in 2018, Second World War veteran Jack Widdicombe last flew a Tiger Moth biplane at age 97, making a couple of passes over his old family farm near Foxwarren.

As grounded as he was, Widdicombe also soared to great heights — literally.

In 1940, he joined the Canadian Officers Program while studying agriculture at the University of Manitoba and two years later enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force. In July of 1943, he sailed to England aboard the troop ship Louis Pasteur. Soon after, the young pilot was assigned to the 419 “Moose” squadron of the RCAF and flew Lancaster bombers over Germany until peace was declared in 1945.

He died in June following a bout with cancer. He was 103.

Penny Menzies says her dad rarely spoke with her and her siblings about his wartime experiences, but those events had a profound influence on him. He viewed the world from a global perspective for the rest of his days.

It didn’t come as much of a surprise when Widdicombe decided to join up. One of 11 children, three of his older brothers had already done so and he felt a patriotic duty to do likewise, Menzies says.

SUPPLIED

Jack Widdicombe – for Passages feature – combining – 1958 Winnipeg Free Press 2024

A 19-year-old Widdicombe originally signed up for the infantry. However, after a few days of basic training, he determined that, at 5-7, he would be at a distinct disadvantage in any ground battle and submitted a request to switch over to the Air Force. The request wasn’t well received.

“The Army guys didn’t have a very positive attitude about that,” Menzies says, laughing.

“(But) the Air Force recruitment office was just across the field from where he was training and he walked over and signed up and said, ‘I don’t want to be in the Army.’ The Air Force was glad to have him. They said the best way to hide from the Army was to join the Air Force. Short, skinny guys were good for (flying) Lancasters.”

In total, Widdicombe took part in 23 missions during the war; only once did his plane incur serious damage. One of those missions was the bombing of Dresden, Germany, that took place between Feb. 13 and 15, 1945. Some 800 bombers took part in the raid that nearly destroyed the city and is viewed as one of the most pivotal and controversial battles of the war.

Although he never talked about the battle, Menzies says it was obvious it still troubled him many years later.

SUPPLIED

A 19-year-old Widdicombe (right) originally signed up for the infantry but switched to the Air Force, keeping in touch with crewmates until 2015, when only he remained.

“There was a big fuss one time about the Dresden airstrike. They were making a big thing about the British bombers being blamed for all the civilian deaths. He was pretty tied up in knots about that,” she says.

“My mother had to explain to us to ‘stay out of dad’s road for a while, he’s not in a very good mood.’ That’s all I heard about it, but I do know that it obviously bothered him.”

Widdicombe flew back to Canada in 1945 and was stationed in Newfoundland. He expected to be redeployed to the conflict in the Pacific but that plan was abandoned after the Japanese surrendered in August of that year.

While he was glad to be done with the fighting, Widdicombe never entirely forgot the war or the people he fought with.

Menzies says there were times her dad seemed to feel a sense of survivor’s remorse, something she attributes in part to the fact that a couple of fellow pilots who swapped leaves with her dad never came back from missions he was originally scheduled to fly.

SUPPLIED

Jack Widdicombe and wife Florence show off his many golfing medals. He celebrated his 100th birthday by playing 18 holes.

Widdicombe stayed in touch with his crewmates following the war and the group used to meet regularly until 2015, when only he remained. That was hardly a surprise considering all they endured together, his daughter says.

“I think that the situations they were in, their lives were dependent on each other. I think when you’re in those kind of life-or-death situations with people, you form a pretty major bond,” says Menzies.

Widdicombe returned to Foxwarren soon after flying back to Canada. One of the first things he did upon his return was to reacquire the family farm — which had gone into receivership while he was overseas — thanks to a loan provided through the Veterans’ Land Act.

At about the same time, he proposed to Florence and they were married a short time later. They originally met as kids when Jack would drive a horse and grain cart from the family farm to an elevator in Chillon that was managed by Florence’s dad. The couple would have celebrated their 77th anniversary on Sept. 23 of this year.

Menzies says her parents were a case of opposites attracting.

SUPPLIED

Jack Widdicombe – for Passages feature Winnipeg Free Press 2024

“My dad was a much more taciturn kind of person and my mom was a very outgoing, social-butterfly type,” she says. “But I think the reason they got along so well was they were both … very, very intelligent. They could share intelligently with each other about ideas or anything. They were kind of the yin and yang of each other.”

One of Widdicombe’s driving passions throughout his life was sports. As a young man, he played hockey in the winter and baseball during the summer.

Interestingly, it wasn’t until age 65, when he retired from farming, that Widdicombe took up golfing. He turned out to be a quick learner. He medalled at multiple Manitoba and Canadian Senior Games and in 2011 earned silver at the International Summer Games in Houston at the age of 90.

He celebrated his 100th birthday by playing 18 holes and continued to golf until his physical health started to decline two years later.

John McNarry got to meet Widdicombe several times over the years thanks to his dad, Leon, who served with him during the Second World War. McNarry was always struck by how pleasant Widdicombe was despite what he must have endured during the war.

SUPPLIED

Jack Widdicombe – for Passages feature – at Lancaster Museum Winnipeg Free Press 2024

“I can’t think what it must have been like to be involved in the fighting,” says McNarry, president of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum in Brandon. “I’ve been in most of those old aircraft, but in peacetime. I can’t imagine having to do the jobs they did.”

One of McNarry’s most enduring memories of his dad’s friend was formed in 2018, when he and fellow museum volunteer Peter Moodie were flying a vintage Tiger Moth plane as part of an airshow being hosted by the Russell Flying Club.

They asked Widdicombe if he would like to go with one of them for a flight in the two-seater, one of the first aircraft he learned to fly. A few days later, Widdicombe was climbing into the plane’s tiny cockpit with Moodie.

Once they were in the air, Moodie asked him if he wanted to take over the controls. He flew the duo over his old family farm near Foxwarren for a couple of passes before piloting the plane back to Russell, where Moodie took over to land it. Widdicombe was 97 at the time but still sharp as a tack, McNarry says.

“He enjoyed that flight thoroughly; I know he did. What impressed me is he could still handle the airplane so well at his age,” he says.

SUPPLIED

Jack Widdicombe – for Passages feature – with wife Penny on her 90th birthday – 2013 Winnipeg Free Press 2024

Menzies says while it was tough to say goodbye to her dad, his was a life well lived.

“It’s sad that he’s gone, but he had 103 years of very, very busy, fulfilling and interesting years, and we’re grateful for that.”