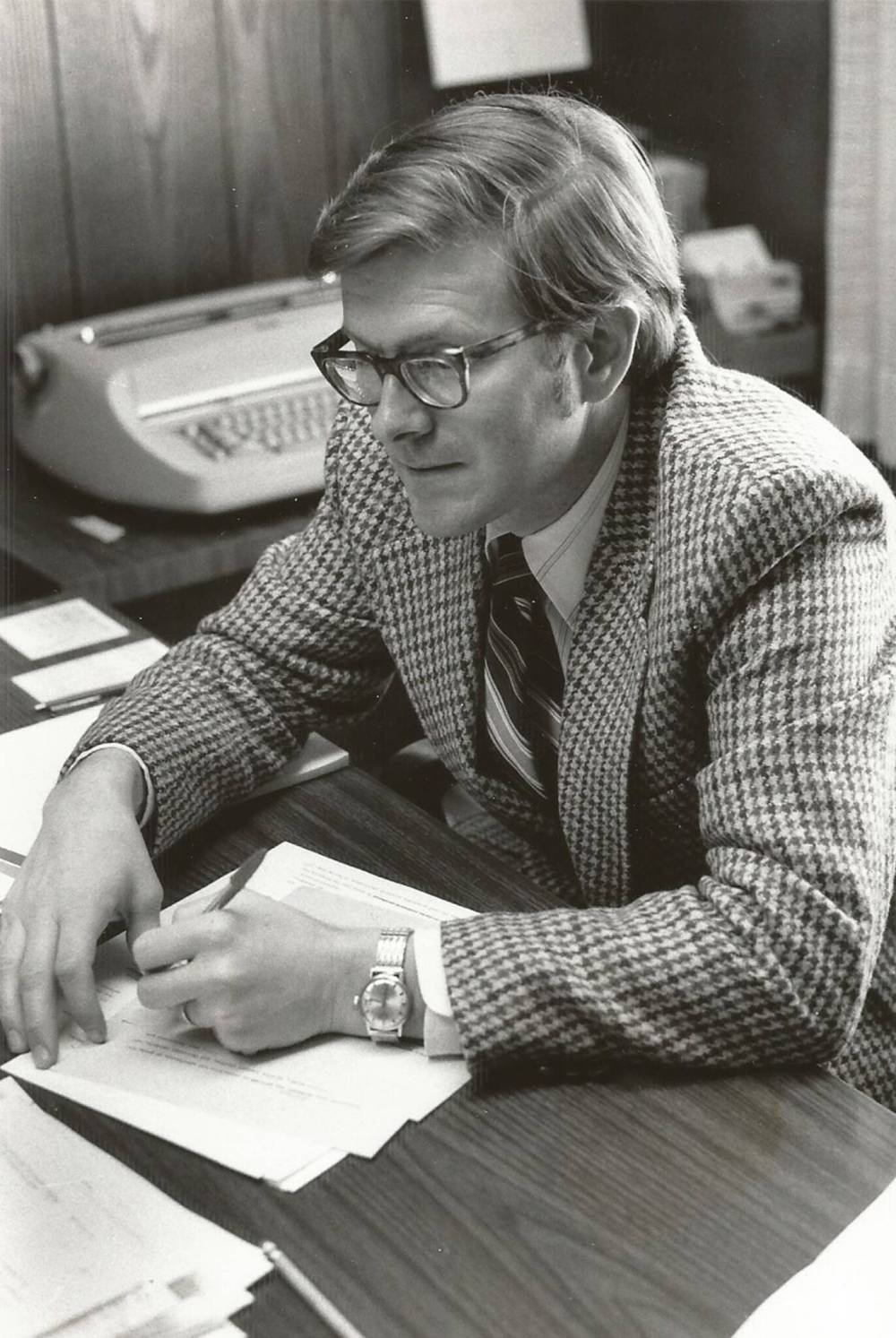

An important figure in the Mennonite community, the nationally known and widely respected writer, editor and publisher Harold Jantz was fascinated with every opportunity to learn. Curiosity fuelled his work.

His faith was at the core of all he did, as was his belief in a good and peaceful world.

For decades, Jantz edited Mennonite and Christian publications. He was the founding publisher and editor of the national evangelical newspaper ChristianWeek, and contributed articles to other publications, including numerous letters and op-eds to the Free Press. Jantz also organized a national Faith and the Media conference in Ottawa in 1996, bringing together several hundred media personnel and faith representatives.

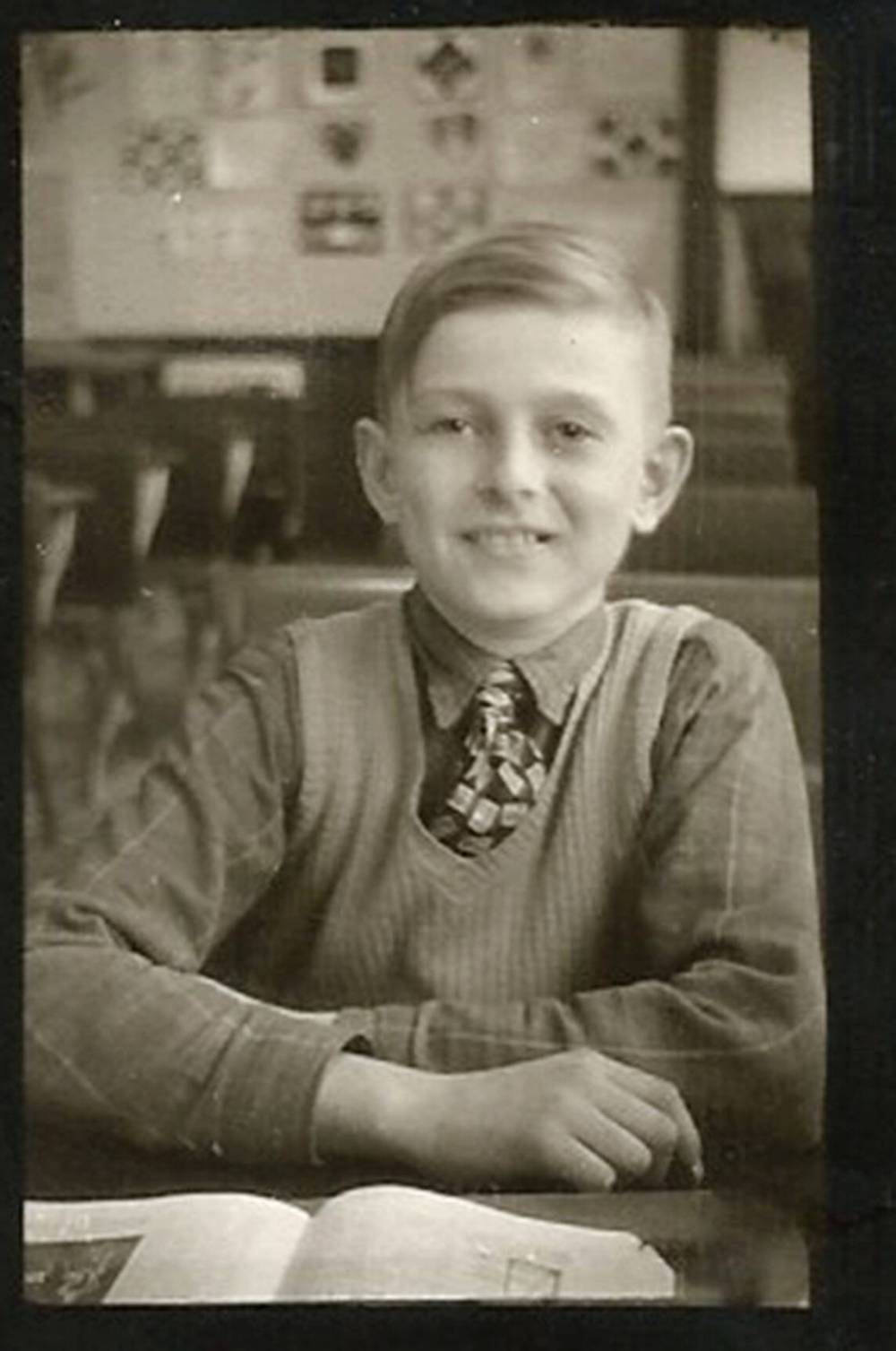

SUPPLIED

Harold as a young boy.

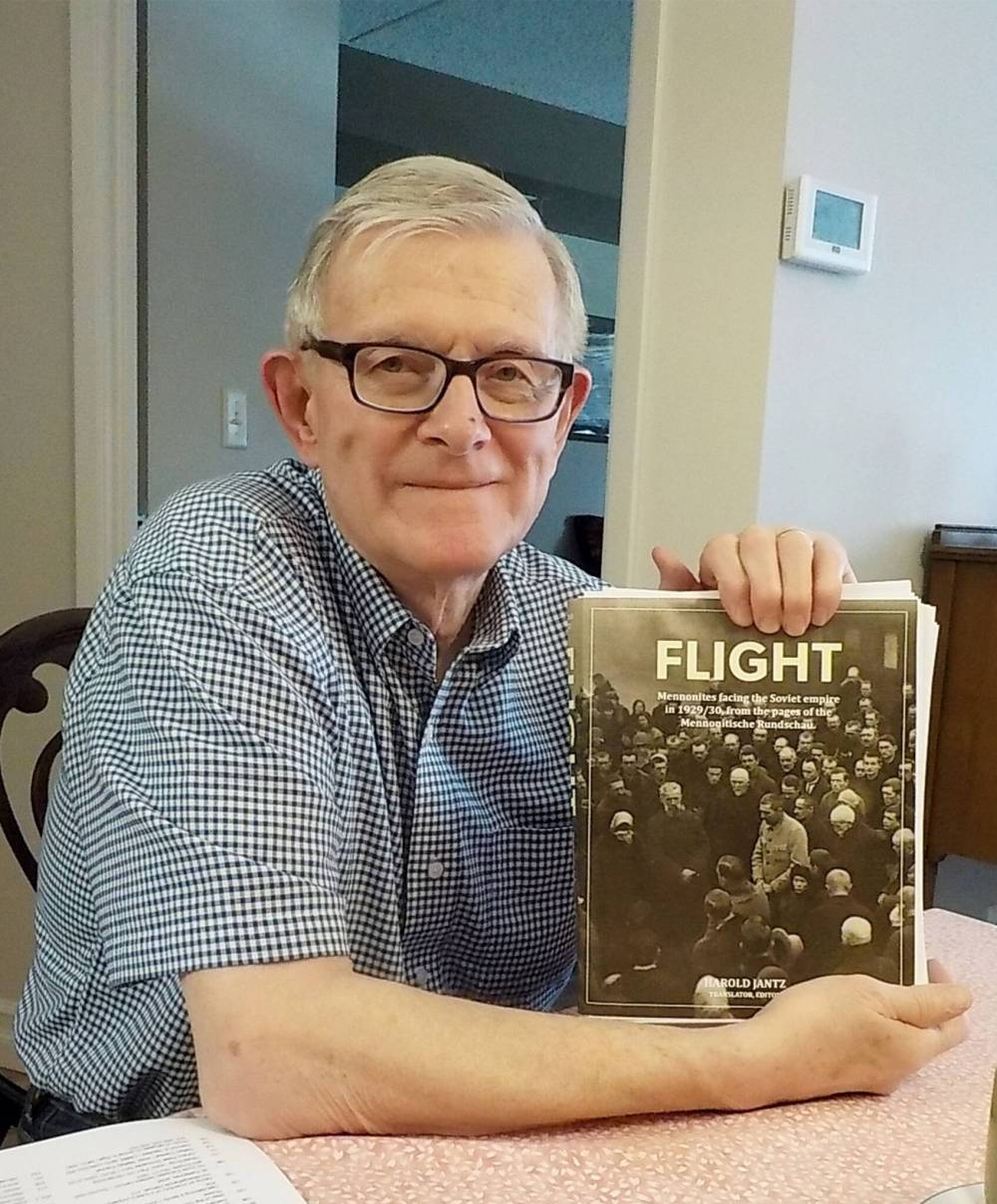

While chronicling his parents’ life history, Jantz eventually compiled Flight: Mennonites Facing the Soviet Empire in 1929/30, from the pages of the Mennonitische Rundschau. The 375-page translation into English of letters from ordinary Russian Mennonites to their relatives in Canada was a labour of love.

Grateful for his life from beginning to end, Harold Jantz was 87 when he died on Feb. 7.

Born in Laird, Sask., to parents who emigrated to Canada from Russia, Jantz enjoyed his early years on the family farm with his six siblings. When he was 10, the family moved to a fruit farm in Virgil, Ont.

He met Neoma Hinz during his studies in Winnipeg, where the couple settled and raised their three daughters. They were married for 62 years.

Eldest daughter Connie says that when she was growing up, it seemed her father knew everyone and everyone knew him.

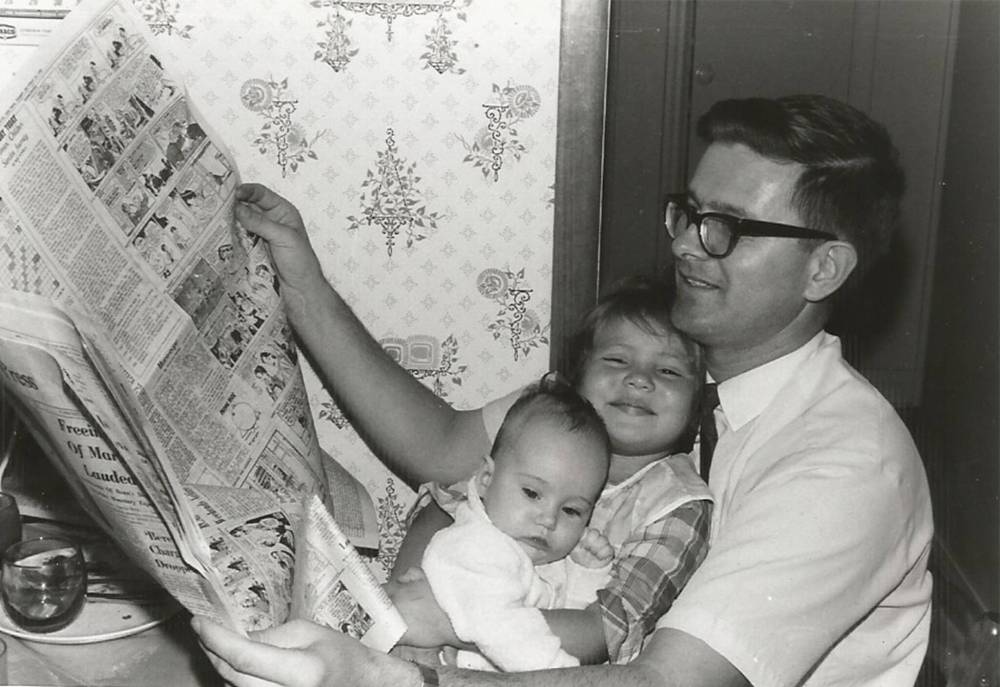

SUPPLIED

Harold and Neoma were married for 62 years.

“He had an innate ability to seemingly remember everyone, how they were connected, their respective roles, their family histories,” she said. “He wasn’t loud and he didn’t need to be the centre of attention, but he was always interested in other people and he was the last person to leave church. As kids, we fell asleep listening to the sound of him typing in his study, because for several years he basically published the Manitoba Herald by himself.”

Although her father held strong options that he wasn’t afraid to champion, he wasn’t rude, egotistical or petty, Connie said.

“Within our family we talked continuously about all manner of topics. As adults, we could disagree about things but still have good relationships.”

Connie recalls asking him about his younger years and being impressed with his ability to remember details.

“I talked to him about where he was born and where he grew up. He closed his eyes and went through the main street of that town and identified every building and everyone who had a business,” she said. “That was normal for him. There was an encyclopedia that went with him when he passed.”

SUPPLIED

Harold with his daughters, Linda and baby Ruth.

In 1978, Free Press faith reporter John Longhurst was a young university student looking for a summer job. He had no experience reporting and had never written a news article before, but Jantz gave him a chance and hired him anyway.

“Harold was my first mentor in journalism, and the Herald was the first place I worked as a writer and reporter,” said Longhurst. “For that, and to Harold, I am deeply grateful.

“I still remember how Harold patiently and pastorally walked me through my very first article. In the most kind and gentle way, he let me know that my very first attempt at writing a news report was absolutely, and unreservedly, terrible. Then he helped me make it better.”

Longhurst said his time at the Herald was a wonderful and creative learning environment; as a mentor, Jantz provided guidance, tips, and ideas to help make him a better reporter and writer.

“He gave me the freedom to explore various issues and topics, to travel and to meet and interview interesting and fascinating people. He nurtured my curiosity and helped me grow as a writer,” he said.

SUPPLIED

From left: Harold, his wife, Neoma, and his daughters Linda, Ruth and Connie.

“Other young, aspiring writers found their first journalism jobs with him there. Through it, we not only learned to love words; we also learned to respect and care for the people we were writing about, to always tell the truth, and to seek the best for the church. Those lessons have stayed with me over my entire career.”

For many years, Doug Koop worked closely with Jantz at ChristianWeek, which explored Christian faith and life in Canada.

“Harold had an enormous sense of personal responsibility and would readily dive into the details of whatever was before him,” said Koop. “He was responsible for the newspaper; he carried responsibilities in his congregation and on various conference committees. He adored his wife and daughters and at times lamented how his work interfered with family life.”

Despite his busy-ness, Jantz found time for a variety of passions, including bird-watching, travelling with his family (most notably an overland trip from Canada to Paraguay, a 22,000-kilometre trek in a Volkswagen van), collecting old Mennonite hymn books and exploring the history of Mennonites in Russia and Germany as they made their way to Canada.

“Harold loved talking about these pursuits, and would often preface his remarks by saying, ‘Now this is very interesting.’ Lots of things were ‘very interesting’ to Harold,” explained Koop.

SUPPLIED

The Jantz family travelled 22,000 kilometres by land to Paraguay in a Volkswagen van.

“When I last saw Harold, he acknowledged his increasing fatigue, observed that his walks were fewer and shorter, and that — week by week — he felt weaker. Yet each day arrived with a to-do list to address. And even as the physical hurdles mounted, he remained concerned about global and community issues. His vision of life’s duties was not dimmed by his own diminution. He remained engaged to the end.”

For those who knew him, Jantz will be remembered not only as a man of faith but as someone who lived it. His funeral featured stories about his compassion for the less fortunate, the times he’d give rides to people on the street who needed them and the day he got out of his car to ensure that a young man and his dog could get to a shelter that would allow pets.

“He was an optimistic, hopeful person. Even in the face of the world that has a lot of really horrific things taking place, he had a lot of hope … a lot of that has to do with his faith,” Connie said.

“My father was dedicated to his faith, which he embraced early in life and never wavered from. It was the lens through which he saw the world and his moral compass in relation to others. It allowed him to die with certitude and in peace.”