First Nations babies have become involved with Manitoba’s child-welfare system at a “shocking” rate over the past 20 years, says the lead author of a new study published Wednesday.

University of Manitoba researcher Kathleen Kenny, a post-doctoral fellow in community health sciences at the Rady School of Medicine, said the need for change is urgent.

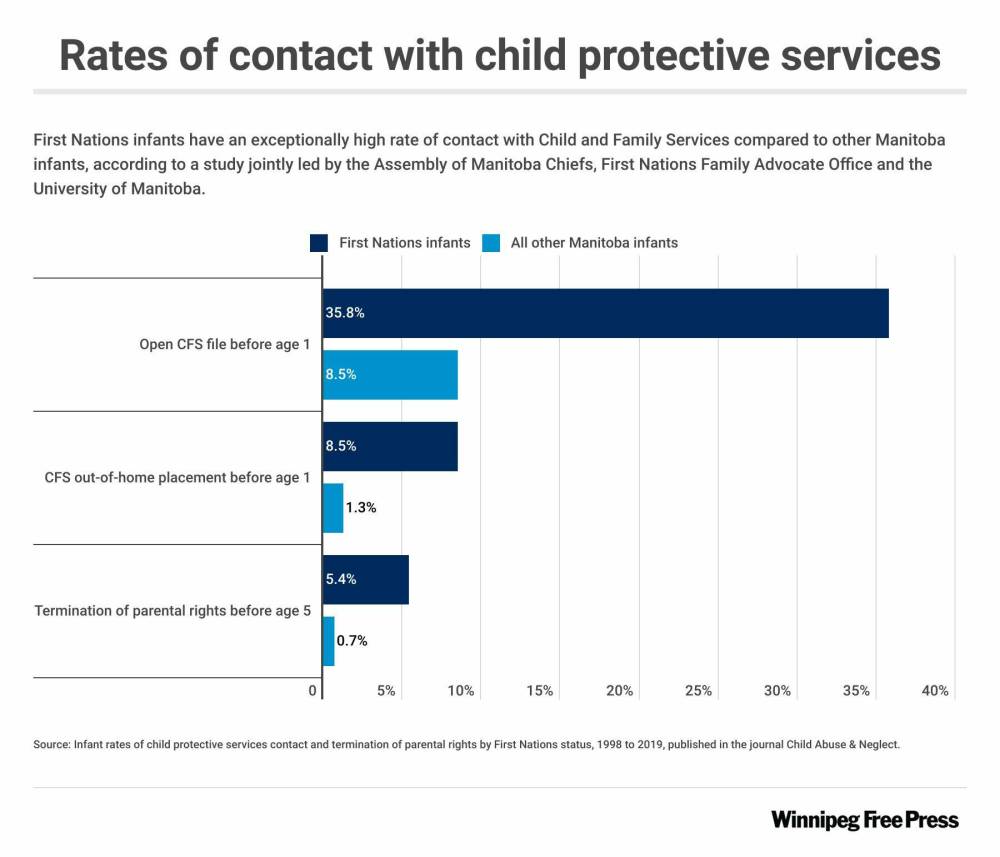

“The findings are shocking when you think one in three of all First Nations infants born in our study period had (Child and Family Services) involvement,” said Kenny.

The research was published in the journal Child Abuse & Neglect.

“Infancy is a common pathway into the system in Canada and we know that Indigenous and First Nation children are at higher risk for CFS involvement.”

Researchers analyzed anonymous government health and social service data for the 20-year period from 1998 to 2019, tracking more than 47,000 First Nations infants and more than 169,000 non-First Nations infants from birth to age five.

“What we found was a 22 per cent increase in CFS contact among First Nations infants and a two per cent increase among non-First Nations infants,” said Kenny.

Federal Bill C-92, relinquished child-welfare authority and funding to First Nations in 2019. So far in Manitoba, only Peguis First Nation has assumed control of its system.

“The underlying message from this work is the need for change is urgent and that First Nations-led solutions need to be prioritized and outside of colonial systems,” Kenny said.

The study highlights the scale of CFS involvement with First Nations and the need for them to care for their own children, said the chair of the Assembly of the Manitoba Chiefs women’s council that oversees the First Nations Family Advocate Office and helped lead the study.

“It brought out the data that show how many children have been taken in the past 20 years,” Chief Betsy Kennedy said.

“It’s had a real effect on these young people; they lose their self-identity and don’t know who they are… 18-year-olds aging out of care without family too often end up homeless and adrift… they don’t want to go back to their families. They don’t know them. They don’t know who they are or don’t want to learn their culture and language.”

Kennedy said she has heard from many mothers of those children who were apprehended as infants.

“It needs to be heard: we want to keep our children home and that they should stay with parents,” she said.

Babies continue to be apprehended at birth for a year or longer, which is harmful to both the infant and the family, Kennedy said.

“It’s devastating for parents and for the extended family and the grandparents. They often wonder, ‘What’s happening with my child?’ and, ‘How do we know this child is being properly taken care of?’”

The consequence of so much “system entanglement” for First Nations families can be to discourage them from seeking help and support out of fear that they’ll be further punished or face negative repercussions if they do reach out, Kenny said.

“If we consider a parent who has children in her care and is facing violence in the home or struggling to afford food — or, like many in the province or the city, is unable to find affordable, livable housing — it can feel very risky to reach out for help because the parents know that the system has an open file on their family.

“(That) makes the threat of having their child or children apprehended much more possible and devastating.”

Families Minister Nahanni Fontaine said the study highlights the “astronomical” rates of Indigenous children versus non-Indigenous children still being caught up in the child-welfare system and its systemic racism.

“These are colonial systems that are contributing to the over-representation of Indigenous children and families within child welfare,” Fontaine told the Free Press Wednesday.

“Instead of supporting the families in what they need, they take the children right away. My priority is transferring the jurisdiction of child welfare back to First Nation communities and First Nation leadership where it should have always been for generations. First Nations will be able to create a system in which they’re supporting the whole family and keeping the family together, and our people know what’s best in respect of the supports that our families need.”

carol.sanders@freepress.mb.ca

Carol Sanders

Legislature reporter

Carol Sanders is a reporter at the Free Press legislature bureau. The former general assignment reporter and copy editor joined the paper in 1997. Read more about Carol.

Every piece of reporting Carol produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.