One in three licensed child-care facility in Manitoba is operating on a temporary “provisional” licence, meaning hundreds are failing to meet minimum health, safety and operating standards, a Free Press investigation has found.

BUILDING BLOCKS, CRUMBLING FOUNDATION

A six-part series examining Manitoba’s crisis in child care

Part 1: Fear and frustration

Part 2: Licensed to fail

Next: Cracks in the system

YOUR THOUGHTS:

We want to hear about your experiences with Manitoba’s child-care system. Responses can be emailed here.

Meanwhile, the scope and severity of inspection infractions are hidden behind a wall of regulatory ambiguity, leaving Manitoba parents in the dark about potential risks at their child’s care facility. The issue is buried in bureauracy to the point the province said it would take more than 8,000 hours — or the equivalent of four employees working an entire year — to compile three years’ worth of child-care centre inspection reports.

“Eight-thousand hours? That’s because they have neglected their obligation to parents for so long,” said Arthur Schafer, founding director of the Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics at the University of Manitoba. “Transparency and openness about this data is really important.”

Schafer added it is “extraordinary” that one-third of Manitoba’s child-care centres don’t have a full licence — and parents deserve to know why.

The lack of basic information, which is readily available in other provinces, makes it nearly impossible to grasp the significance of so many centres operating provisionally, experts say, though it’s clear, in some cases, longstanding systemic issues are keeping facilities trapped in infraction cycles. Part 2 of a Free Press investigation into Manitoba’s child-care system examines licensing requirements and oversight.

In March, the Free Press analyzed the limited publicly available licensing information for Manitoba’s 1,110 licensed child-care centres, nurseries and home-based daycares. The analysis found 383 facilities — slightly more than one-third — had “provisional” licences, meaning an inspector found there was at least one area in which the centre or home did not meet the province’s required minimum standards, or the centre is new and requires further assessment. Provisional licences are temporary, issued until the centre comes into full compliance with regulations.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS

University of Manitoba professor Arthur Schafer, founding director of the Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics, says there is more oversight in the food industry than child care.

A shortage of qualified staff, which is a longstanding problem in the child-care sector, was a common infraction.

Other notable infractions included missing criminal and child abuse registry checks for staff, unspecified health and safety hazards, and poor recordkeeping. And in nine cases, centres were flagged for being non-compliant with child-abuse reporting.

The details about each infraction are minimal, with regulatory jargon that is difficult to decipher noting the relevant section of the Community Child Care Standard Act.

Staffing issues, for instance, were flagged on provisional licences as follows: “Regulation 62/86 Sections(s): 7(4) Proportion of Trained Staff.” No additional information is provided.

The available information also makes no reference to past inspections or any previous outstanding issues.

Schafer questions why there is more rigorous oversight of the food industry, where infractions — such as the presence of rodents at restaurants — are publicized on the province’s Health Protection Report website and lead to immediate closures until remedied.

“Why is it more important to protect food safety by publicizing it than to protect child safety?” Schafer asked. “It’s kind of shocking.”

Tracking infractions

Licensing orders issued by the province of Manitoba since Jan. 1, 2023.

Licensing orders issued by the province of Manitoba since Jan. 1, 2023:

ST. JAMES EARLY LEARNING PROGRAM, WINNIPEG, JAN. 9, 2024

Issue: A child was left unsupervised for two minutes in a room. Children were using the washroom without direct supervision. Other “serious” licensing infractions noted during an inspection include: an out of date record of employees, an unstable shelf not secured to the wall and the door to an electrical room was unlocked.

BRIGHT BEGINNINGS EDUCARE INC. (MONTEREY SITE), HEADINGLEY, DEC. 22, 2023

Issue: A 26-month-old was left unsupervised in the facility’s fenced outdoor playground for 18 minutes.

PLAY N LEARN CHILDCARE, WINNIPEG, OCT. 26, 2023

Issue: The group child-care home was caring for more children than its licence permits.

FUZZY BEARS INC., BRANDON, OCT. 24, 2023

Issue: A four-year-old was left alone at a community park for at least 20 minutes. A resident found the child under a slide and brought them to a local community centre.

CENTRE D’ENFANTS SAINT CLAUDE CHILDREN’S CENTRE INC., ST. CLAUDE, JUNE 16, 2023

Issue: A three-year-old left a fenced facility playground and was found three to five minutes later, 70 metres from the playground. In another incident, a twoyear-old left the fenced preschool area and entered the adjacent fenced infant area. The child was unsupervised for five to 10 minutes. Upon inspection, safety concerns were documented regarding the height of the fence, spaces in the fence, with temporary fencing and a gap under a gate.

RIVER ROAD CHILD CARE CENTRE, WINNIPEG, JUNE 2, 2023

Issue: A two-year-old was left unsupervised during a fire alarm at the centre for two to three minutes. Staff woke children up from their naps when the alarm rang but did not notice a child was missing until they went outside. They found the child asleep in a sunroom. Children were left alone in two other incidents: a threeyear-old was left alone for one to two minutes in a hallway and a three-year-old child was left alone for five to 10 minutes in a washroom.

KOOKUM’S PLACE PRESCHOOL CENTRE, WINNIPEG, MARCH 6, 2023

Issue: A 27-month-old was left unsupervised in a classroom for two minutes.

KOOKUM’S PLACE INFANT CENTRE, WINNIPEG, MARCH 30, 2023

Issue: A 23-month old was left alone outside in fenced playground for six minutes.

In rare cases, Manitoba posts more information about child-care issues deemed “serious” through a licensing order, which the province publishes online. Licensing orders detail specific issues that make a facility hazardous to the health, safety or well-being of children, including if children have been left alone outside, for example.

Since the beginning of 2017, 14 licensing orders have been issued, including seven in 2023.

Susan Prentice is a professor of sociology specializing in child-care policy at the University of Manitoba. She said while it’s problematic that one third of child-care centres are operating with temporary licences, it’s more important to look at why the system allows them to persist.

“Squint with one eye and of course, it’s terrible,” Prentice said. “These are pretty minimum standards and they should be met.”

She said high rates of provisional licences have long been the status quo. She points to a 2013 Manitoba auditor general’s report that found one in four centres had provisional licences.

“This was because of a staffing crisis, which we know has been going on for decades,” she said. “We’ve clearly, as a province, continued to live with the practices that produce these results.”

BROOK JONES / FREE PRESS

University of Manitoba sociology professor Susan Prentice says parents need information to be able to make choices about their children’s care based on the quality of child care being delivered, as well as whether or not the facility meets basic public health and safety standards.

Jodie Kehl, executive director of the Manitoba Child Care Association, said because licences are issued on an individual basis and details are vague, it is difficult to know the true extent of broader problems.

However, Kehl said, the longstanding shortage of trained staff in Manitoba — ratios of which are established by government regulations — is well-documented, and there may be administrative reasons for missing child abuse record checks, such as a backlog at the provincial level.

Regardless, Kehl said Manitobans should expect more from the child-care system.

“Would you open a hospital if you didn’t have enough doctors or nurses?” she asked.

Kehl stressed Manitoba’s child-care sector is heavily regulated and facilities are expected to comply with the extensive list of requirements outlined in the Community Child Care Standards Act regulations.

“You can put up the four walls and call it child-care spaces, but unless you have nurturing, trained professionals, it’s just hiring warm bodies.”–Kisa MacIsaac

But some child-care facilities are never going to meet the act’s bare minimum, such as having at least one room with natural light, Kehl said.

“I’m in the basement of a church and there’s no windows, there’s not enough natural light,” she said. “It’s kind of out of your control.”

While the provisional licences are intended to be temporary — lasting three months — Kehl said she knows of at least one facility that’s been operating on a provisional licence for 10 years.

Kisa MacIsaac said the rate of centres on provisional licenses for not having enough trained staff is troubling. She has seen first-hand what happens when a centre is only meeting minimum standards.

“You can put up the four walls and call it child-care spaces, but unless you have nurturing, trained professionals, it’s just hiring warm bodies,” she said. “That’s not high-quality, early learning and child care. It’s just keeping kids alive until their parents get back from work.”

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS

Some Manitoba child-care centres are operating under provisional licences, meaning they do not meet the province’s required minimum standards.

The Free Press’s analysis shows varying rates of compliance, depending on the type of facility.

Manitoba’s licensed centres include: home-based child care, where care is provided out of a home with capacity limitations; nursery schools, where child care is offered for a limited amount of time each day or week, with age restrictions; and child-care centres, where care is provided for longer hours and to more children.

One in four home-based centres, one in three daycare centres and more than one in three nurseries had provisional licences.

What’s missing

Free Press analysis of licensing data shows:

● 144 centres lacking the required proportion of trained staff, specifically: “Two-thirds of all staff who care for children in a full-time child care centre and are included in the staff-to-child ratio, shall meet the requirements of an E.C.E. II or III”;

Free Press analysis of licensing data shows:

● 144 centres lacking the required proportion of trained staff, specifically: “Two-thirds of all staff who care for children in a full-time child care centre and are included in the staff-to-child ratio, shall meet the requirements of an E.C.E. II or III”;

● 55 centres lacking trained staff per group, specifically: “7(7) At least one staff person per group of children in a full-time or school age child care centre shall meet the requirements of an E.C.E. II or III”;

● 67 centres missing public health inspection checklist or lacking compliance with checklist;

● 46 centres missing fire inspection report or lacking compliance with fire inspection report;

● 42 centres missing first aid and CPR training or recertification;

● 10 centres missing a child abuse registry check, including for residents who live in the home offering child care;

● 9 centres missing a criminal record check, including for residents who live in the home offering child care;

● 9 centres not compliant with health regulations and guidelines for food storage, handling and serving;

● 9 centres not compliant with child abuse reporting, specifically: “Every licence holder shall immediately report … any case of suspected child abuse relating to a child attending the licence holder’s child care centre (or family home) to the Director of Child and Family Services or a designated child caring agency as required by the Child and Family Services Act or any similar legislation.”

*Analysis based on Manitoba Education and Early Childhood’s child care licensing data, as of March 2024.

This data is limited to when the analysis took place — in March. Provisional licence numbers can change throughout the year, depending on when inspections occur.

In addition to the option of issuing a provisional licence, the province can suspend or cancel a licence. The province said it has not cancelled a licence in the last 10 years and has suspended only one.

It’s unclear the extent to which the Manitoba government tracks provisional licences, a problem exacerbated by a reliance on paper-based records up until last year. When asked how many are issued annually, a provincial spokesperson said the number varies.

Asked to confirm the province doesn’t know the exact number, the spokesperson said: “No one said the province ‘doesn’t track’ the number of provisional licences — we said the number varies… The number could literally be different every day.”

Still, no annual number was provided.

The spokesperson added: “Please don’t assume things are all digital. The information could be in each co-ordinator’s file, and to check they would have to each go through their files and tally the centres under their supervision. What we’re saying is the number may be hard to compile, not that we don’t have oversight or tracking of each centre.”

It’s unclear what information is still not digital. The province posts provisional licence information for each centre online and says its inspection reports — which detail infractions that lead to provisional licences — have been electronic since 2023. As for the number of co-ordinators, there are 29 licensing and compliance co-ordinators, four supervisors and one manager.

The Free Press sought further clarity and filed a freedom of information request for inspection records for the last three years. The province rejected the request outright, saying it would take more than 8,000 hours to compile. The Free Press is appealing the decision.

“That just seems kind of preposterous,” said Kevin Walby, a University of Winnipeg criminologist who runs the school’s Centre for Access to Information and Justice.

“It tells us a little about the state of record-keeping in the provincial government … it just speaks to the disarray.”

It is also unclear how many inspections, including those for annual re-licensing, unannounced visits and others, even took place over the three-year period from 2021 through 2023. The province paused re-licensing inspections at the end of March 2020 based on pandemic public-health orders. They resumed in May 2022.

The province’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act rejection letter stated the Free Press could contact each of the 1,110 centres individually and request the inspection records, but “it would be up to the facility to decide if they would provide you with their records or not.”

“Ethically, the government needs to step in when consumers can’t make informed decisions on their own.”–Neil McArthur

Neil McArthur, a philosophy professor at the University of Manitoba and current director of its Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics, said the province’s response suggests individuals — specifically, the parents of young children — are responsible for seeking out answers.

“Ethically, the government needs to step in when consumers can’t make informed decisions on their own,” McArthur said.

He slammed the province for its poor record-keeping and its reliance, until recently, on paper-based inspection reports.

“That is, in itself, insane,” he said. “We’re talking about the year 2022 and we’re talking about one of the most important records in some sense that the provincial government has.”

Outside of Manitoba, detailed inspection information is readily available.

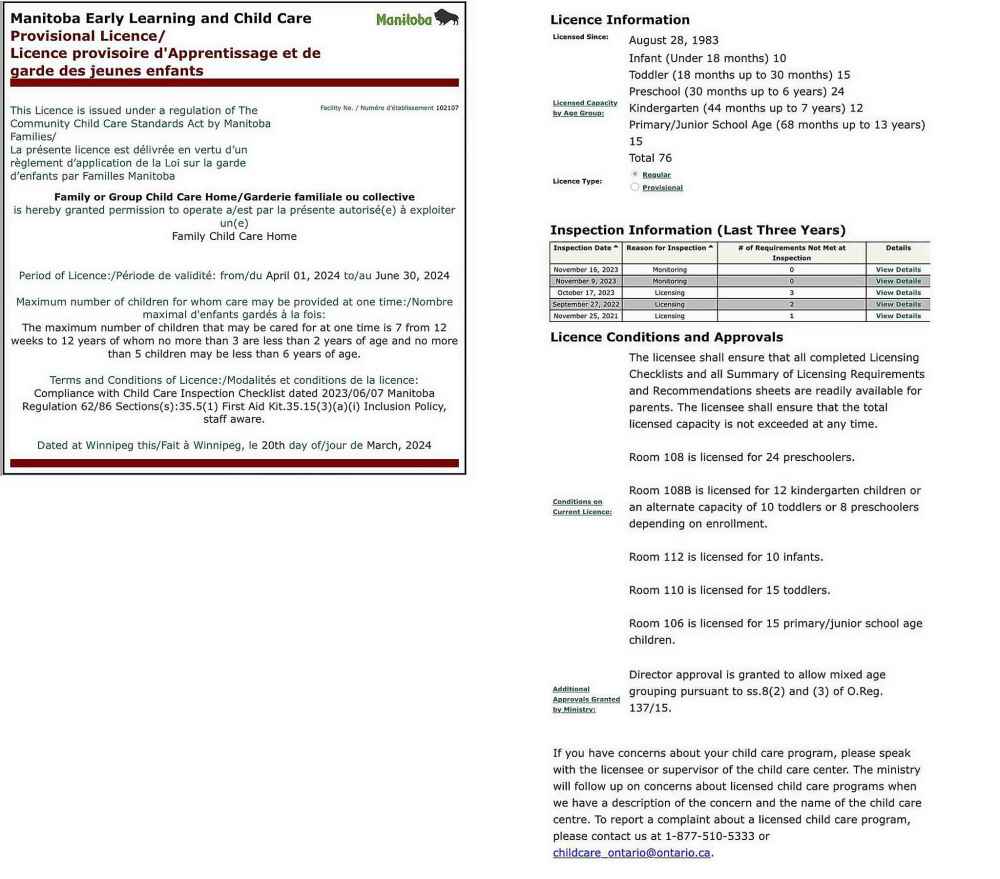

In Ontario, the public can access records for child-care facilities dating back three years. The records include: when inspections took place; why (for instance, for licensing or monitoring); the number of requirements not met; the “risk level” for each missing condition, such as critical — meaning there may be a “direct threat to a child which could result in/has resulted in serious harm to their health, safety and well-being” — high, moderate or low; a list of conditions on the licence; and other inspection findings.

In British Columbia, granular details such as “mould found on carpet” are publicly documented.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, the province posts a list of “violation orders” issued within the last 90 days.

The fact other provinces share more information suggests Manitoba is falling behind on best practices, McArthur said, adding the lack of rigorous record-keeping means the province is unable to identify trends or other important data.

These issues are not new.

A 2013 report from the Office of the Auditor General of Manitoba highlighted concerns around the lack of licensing clarity and transparency.

“Standards violations were listed on licences in an abbreviated form under a heading labeled ‘terms and conditions,’ which did not clearly communicate that standards were not being met,” the report stated. “For example, parents might interpret ‘proportion of trained staff’ on a licence to mean that the facility must maintain a certain proportion of trained staff. But it actually means that the facility is operating without the required proportion of trained (educational childhood educators).”

The auditor general’s report called on the province to improve publicly reported information by “ensuring facility licences clearly communicate all legislated standards not being met” and by reporting the province-wide level of facility compliance with key standards.

In 2017, a follow-up report to the auditor general’s original recommendations stated, “the Department plans to improve how licences communicate facility non-compliance with standards once an upgrade of the IT system is done.”

It remains unclear what steps, if any, were taken to achieve this goal.

Neither the province’s spokesperson nor Education and Early Childhood Learning Minister Nello Altomare would say whether the province would commit to making more inspection information public.

The map below shows Manitoba child-care centres operating on full (green) or provisional (yellow) licences. Drag and zoom the map to navigate the province; click on any icon for details on its licence status. The map can also be viewed online here: wfp.to/childcaremap

In rare instances, the province releases more information about specific incidents at child-care centres via licensing orders.

The province says such orders are issued in cases where there are “serious and/or ongoing infractions,” the facility is being operated “in a manner that is hazardous to the health safety or well-being of children” or it is not in compliance with regulatory standards.

Children being left alone was the most common reason for licensing orders in recent years.

In December 2023, a 26-month-old was left unsupervised for 18 minutes in a fenced outdoor playground at a Headingley facility.

In September 2023, a four-year-old was left alone at a Brandon community park for at least 20 minutes and was found by a resident.

Other children were left alone for a few minutes at a time, including one incident where a two-year-old was left alone napping for two to three minutes during a fire alarm.

The licensing orders include specific details of what happened, where and when, and which regulatory matters that the facilites were found to have violated. The orders outline the steps required to bring the facility into compliance. The province posts all licensing orders online, dating back to 2006.

At the end of the day, child-care experts are less concerned about the transparency issues and more worried about the quality — and availability — of child care.

Other resources

“It’s not quite like parents fully get to choose” where their children go, said Prentice, the U of M professor, referring to the long wait lists and the desperation parents may feel trying to secure child care. “Parents are making choices but not under conditions of their own choosing.”

Prentice noted that while parents want to know more about the facilities their children are attending, the licensing information only assesses if a centre is meeting the basic public health and safety standards. It doesn’t address quality of programming or supports offered.

“Licensing is not quality assessment,” she said.

Martha Friendly, executive director of the national Childcare Resource and Research Unit, based in Toronto, agrees. In addition to the province needing to be more transparent about the infractions, parents deserve to know more critically important information, such as who the staff are, their education and experience, she said.

“Licensing is a minimum,” Friendly said.

While licensing assessments still regularly take place, quality assessments have gone by the wayside.

Ten years ago, the Manitoba government used to assess and rate the quality of its child-care centres using standardized assessments called ECERS and ITERS, or the early childhood and infant/toddler environment rating scales. These assessments evaluated everything from the overall quality of programs to furnishings to outdoor space.

According to 2014 statistics previously obtained by the Free Press, Manitoba’s centres were earning an average score of 4.7 out of a possible seven. A score of five is considered good. The province, however, did not share the scores for individual facilities at the time.

The province made the rating system optional a year later. Officials promised Manitoba was shifting to a risk-based assessment approach, but did not elaborate further.

Is a new quality assessment in place today?

Ruth Bonneville / Free Press

Failing to meet minimum regulatory standards is concerning and points to longstanding issues the sector faces, says Manitoba Child Care Association’s Jodie Kehl.

“No,” said Kehl, executive director of the Manitoba Child Care Association.

Kehl said while the ECERS/ITERS system wasn’t perfect — it was criticized for demanding too much from thinly stretched child-care operators — it at least gave facilities an opportunity to reflect on how they could enhance quality.

Asked what, if any, system the province currently uses to evaluate quality, a spokesperson suggested standard inspections include quality assessment. The evaluation includes “staff interaction with children, play time and facility practices,” the spokesperson said.

However, the inspection reports that would detail the findings of these assessments are not made public.

The spokesperson added: “the current curriculum framework will be undergoing a review this year, and part of this will also include assessing tools for evaluating the quality of child care services.”

It’s unclear what this might involve.

“What are we doing to ensure that we are creating that quality system in our province?”–Jodie Kehl

Kehl said child-care centre operators want the best for their kids, but the entire sector is short-staffed, leaving facilities with too few resources to go above and beyond.

“Quality is obviously synonymous with the workforce,” she said. “What are we doing to ensure that we are creating that quality system in our province?”

Prentice said the province needs to shift how it thinks about child care — and how it invests in it — to improve quality.

“We haven’t thought of this as a social project, we haven’t tended to think of it as a government responsibility,” she said. “We’ve been content to largely leave it to the private market.”

She is cautiously optimistic that things could change.

“We’re in a historic moment where that old understanding is crumbling — but we don’t have a new understanding of how to do things better.”

— With files from Jeff Hamilton

katrina.clarke@freepress.mb.ca

Katrina Clarke

Investigative reporter

Katrina Clarke is an investigative reporter at the Winnipeg Free Press. Katrina holds a bachelor’s degree in politics from Queen’s University and a master’s degree in journalism from Western University. She has worked at newspapers across Canada, including the National Post and the Toronto Star. She joined the Free Press in 2022. Read more about Katrina.

Every piece of reporting Katrina produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.