KHARKIV, Ukraine — Luka huddled in the foxhole as the growl of Russian tanks crept closer, their steel tracks chewing at the grassy fields of eastern Ukraine. For over two hours, the 33-year-old Croatian and his fellow fighters with Ukraine’s International Legion had been hunted by the drones that prowled the skies around Ternova, a tiny village just five kilometres from the Russian border. Now they were pinned, with no escape.

Tank shells ripped through the lip of the trench. Shrapnel pierced Luka’s right arm and then his leg. He fumbled to tighten two tourniquets, but couldn’t get a strong twist. Beside him, Michael O’Neill, a 47-year-old Australian they called Taz, lay dead. Luka radioed for help but the rest of his company, he thought, was still far away.

SUPPLIED

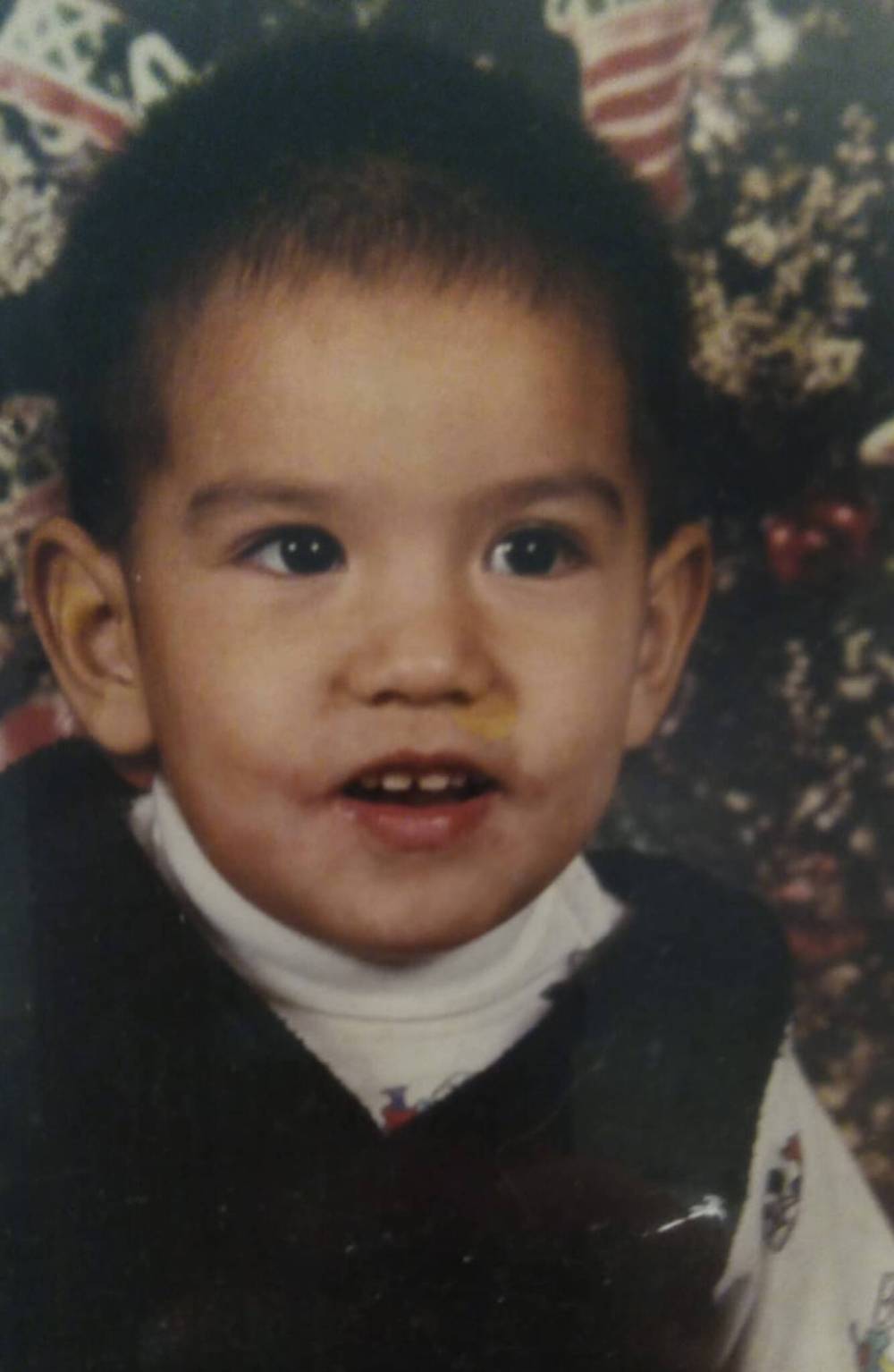

Austin Lathlin-Bercier was the first Manitoban known to be killed in combat in Ukraine. He was 25 years old.

Suddenly, a pair of boots landed in the foxhole beside Luka. The wounded man looked up to see the calm brown eyes and slight, wiry frame of a young soldier from Canada, who went by the call sign Native. He wrenched Luka’s tourniquets to stop the bleeding, then grabbed the Croatian by the straps of his body armour and began to haul him out of the trench.

“F—, you’re heavy,” Austin Lathlin-Bercier grunted.

If there was one face Luka most wanted to see in that moment, it was Austin’s. The two had met in early March 2022, just days after the full-scale Russian invasion, at a base flooded by would-be foreign fighters in Yavoriv, near Ukraine’s western edge. Shortly after arriving, Luka was in line at the cafeteria when a guy in front of him sneezed.

“God bless you,” Luka said.

Austin’s reply was sardonic. “I don’t need the blessings of your god,” he quipped.

Despite that odd first meeting, in the days that followed Luka and Austin became bunkmates and then friends. They’d come from very different worlds: at 23, Austin was younger than the Croatian, and had grown up in the wilds of Manitoba’s north. Yet in the ways that mattered amid the chaos of war, they had much in common. They had the same sense of humour, dry and a bit dark; and while neither had ever been in combat, both felt an intense draw to help defend Ukraine and its people.

SUPPLIED

Luka and Austin Lathlin-Bercier shared a deep bond after the Manitoban saved the Croatian soldier’s life.

Just before dawn on March 13, 2022, they faced their first terrifying test. As most of the volunteers slept, a massive cruise-missile barrage struck the base, killing dozens. Explosions rocked the barracks, as Luka and Austin fled outside to a helicopter pad. There, as Luka stood and took stock of the situation, he glanced over to see Austin casually filming the strikes on his phone.

It was his first experience of a trait he and other soldiers would come to trust with their lives: nothing ever seemed to rattle Austin.

“I respected this man because he made it out of the barracks with his shoes and his jacket,” Luka says with a laugh, chatting over a Zoom call late last year. “He was so calm, more than me… after the cruise-missile attack, I had confidence that he would continue the mission.”

In the wake of that attack, most of the volunteers left, shaken by the brutal reality of fighting a war in a country without air superiority. At the base, men stood in long lines to turn in their weapons. One platoon leader went to each of his soldiers asking in turn for a decision: would they stay and go to war? Were they ready to make their commitment?

When the officer reached Austin, the young man hesitated for a moment, then shrugged.

“F— it,” he said. “I’ll stay.”

That was the beginning of what would become the International Legion’s Bravo 2 Company, a tight-knit group of volunteers from across the world. From then on, they lived, worked and fought together, trudging across battle-scarred fields in Ukraine’s battered margins. They slept in barns, root cellars and abandoned houses. Like Austin and Luka, most had no combat experience, though they would soon face down artillery, tanks and ever-present cheap drones armed with grenades.

SUPPLIED

Austin (right) with two of his brothers-in-arms in Ukraine’s International Legion.

And on nights when there was nothing to do but hunker down and wait, they’d talk about their lives, their families and where they’d grown up. It was then that Austin told them about his home of Opaskywayak Cree Nation, located about 630 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg, on the banks of the Saskatchewan River. He was proud of his heritage and where he’d come from: On the left arm of his fatigues, he wore a patch of a skull bearing a First Nations war bonnet and a banner that read “Native Pride.”

Some of his fellow soldiers, many from Europe with little knowledge about modern Indigenous life in North America, were curious. (“I didn’t know Canada still had tribes,” Luka says. “It was pretty cool.”) Austin would answer their questions with a frank honesty, telling them about his community, about the generational trauma that flowed from colonization and his dreams that more Indigenous youth would go on to higher education.

Before long, the unflappable spirit that first showed during the Yavoriv attack made Austin the “anchor” of Bravo 2, says Craig, a Brit who’d also met Austin during those first days of March. (Many foreign fighters in Ukraine prefer their last names not be used, for safety.) His comrades never saw him angry or heard him shout. He had the same calm demeanour in every situation, they all say, whether he was relaxing at their base on a day off, or flattened on the ground as grenades burst around them.

“Nothing ever fazed him.”–Craig, a fellow member of Brave 2

So Native, as they often called him, became the guy they most wanted to have beside them when things got rough. He always saw clearly. On one mission, when a fellow soldier began trembling from shell shock, it was Austin who first spoke up to say the man needed help; on another occasion, when a tank blast nearly smashed through the ceiling of the root cellar in which they were hiding, Austin didn’t flinch, but just calmly put on his helmet.

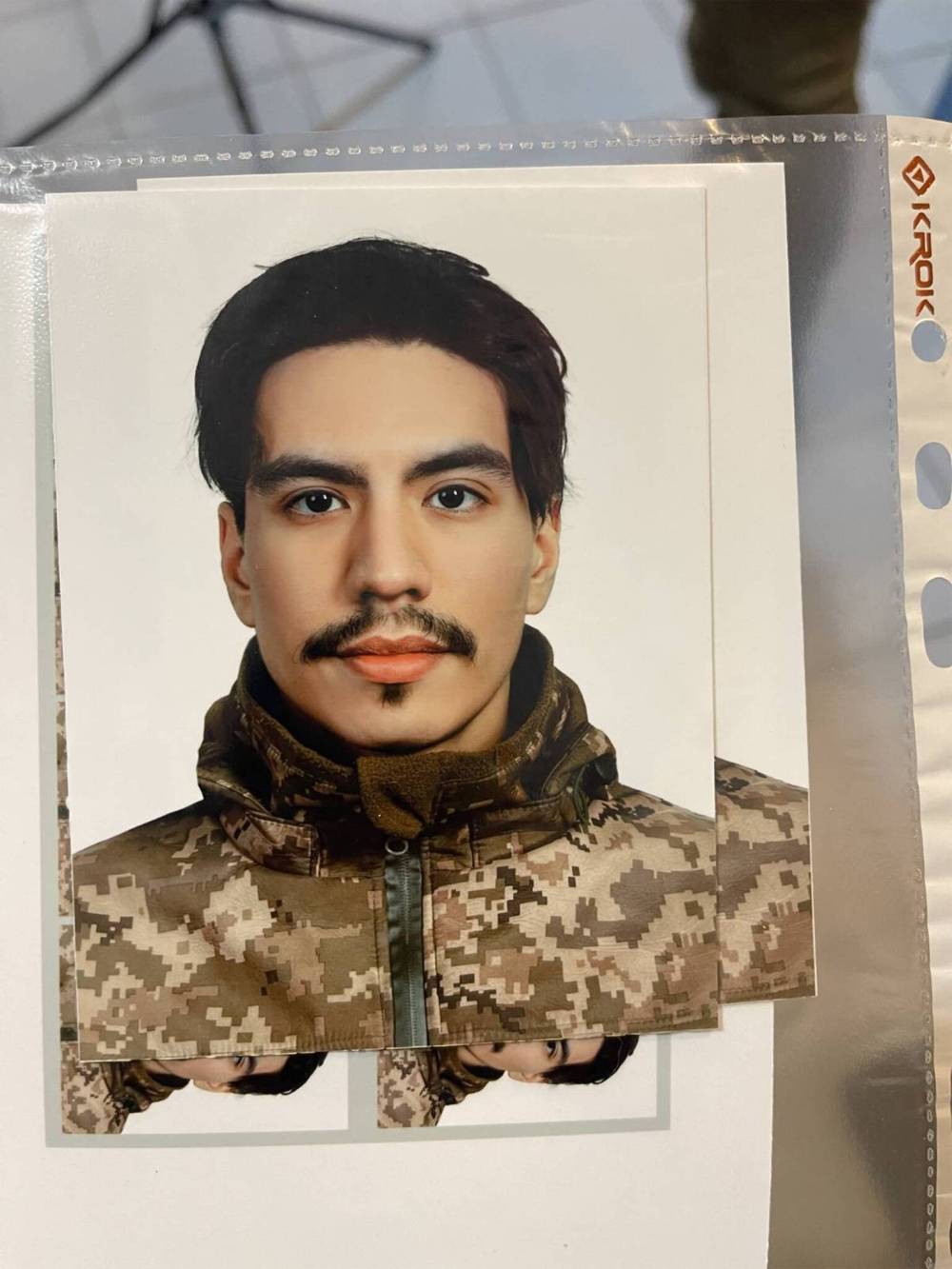

SUPPLIED

Austin Lathlin-Bercier was proud of his heritage. He wore a patch of a skull bearing a First Nations war bonnet and a banner that read “Native Pride.”

“Austin would just stand back like, ‘OK, it is what it is,’” Craig says. “There is no argument from him, ever. It was just, ‘this is what we’re going to do, it’s shit but we’re going to go do it.’

“Nothing ever fazed him. We could be being artillery-ed and he’s just chill, like ‘yeah man, it happens,’ and then we’d get up and do the job.”

So on that deadly mission in late May 2022, as Luka was bleeding out in a trench, it didn’t surprise him Austin got there first, risking it all to save a friend. As the tanks kept firing, Austin and two other soldiers picked Luka up and began hauling him 100 metres through the fields, toward where a medic was waiting.

By the time they reached the medic, Luka was fading. Reeling from blood loss, slipping out of consciousness as morphine flooded his veins, the Croatian turned to his friend and entrusted him with one last request.

“Can you call my sister when I die?”

Austin brushed it off. “You won’t die.”

“Don’t f— with me,” Luka gasped. “You will call my sister when I die. Swear to God.”

This time, the laid-back young man from Opaskwayak Cree Nation agreed.

“Yes, I swear to God,” Austin said. But in the end, he didn’t have to make that call.

In a way, Lucy Lathlin thinks, it was like her son always knew where his path was leading. There was a time, long before the full-scale war in Ukraine, when Austin came back from a sweat-lodge ceremony and told his mother he’d received a vision. It was “something really scary,” he’d said, adding he couldn’t tell her more about it.

“I just wanted to let you know that something is going to happen, mom,” he said, but by his voice she could tell the teenager was not afraid, so she didn’t push the matter further.

Besides, Lucy trusted Austin to find his path through difficult times. It was a faith she’d learned from being his parent. He was her first child, the eldest of her and her husband Adam Bercier’s seven kids. When he was born, she cradled his tiny body to her chest and filled it with a wish, praying that he would grow up to have opportunities she and her husband never had.

“I wished that he would break the cycle, and travel the world, and meet people, and just be a good person,” she says, speaking on a video call from her home in Manitoba earlier this year.

SUPPLIED

From the time Austin Lathlin-Bercier was a toddler, he’d been fascinated by all things military.

As a boy, Austin’s boundless curiosity promised to fulfil that wish. He loved nature and delving into the forests around Opaskwayak. “He was always exploring, and he had just the cutest little expression when he wanted to know what was happening,” Lucy says. He liked to collect bugs in jars and called them his friends; later, he found an adolescent knack for building computers from spare parts.

Yet despite his many talents, Austin struggled as a teen. He often felt alone, Lucy recalls, and ached to find a purpose. He thought about dropping out of school. Sometimes she’d find him crying, saying he felt worthless. She’d hold him then, just like she did on the day he was born, and tell him how much his family loved him, and how she knew he’d find his way someday.

When Austin was 17, the direction he was searching for finally came, when a recruiter from the Canadian Armed Forces’ Bold Eagle program for Indigenous youth visited his school. The paid summer program combines cultural teaching from elders with military training and gives youth a direct path into the Canadian military after they’re finished.

Right away, Austin was intrigued. From the time he was a toddler, he’d been fascinated by military things: as a boy, his parents always bought him soldier toys for Christmas. In his teens, he revelled in war movies, such as Saving Private Ryan. So after learning about Bold Eagle, he asked his mother to sign him up; soon, he was off to British Columbia to join the program.

SUPPLIED

As a boy, Austin Lathlin-Bercier loved nature and delving into the forests around Opaskwayak Cree Nation.

His first weeks in Bold Eagle were tough, being so far from home. But his parents urged him to stick with it a bit longer, and before long Austin was thriving. He learned how to handle military weapons, and soon became proficient; he met with elders and went to Indigenous ceremonies, finding a new love for his culture. For the first time in his life, he was also earning money, which seemed to put a new “pep in his step,” his mother recalls.

“When he came back, he was totally different,” Lucy says. “He had a self-assurance about himself again. He walked with a purpose. It was really beautiful to see when he came home and he was always smiling more. He just seemed so confident, so sure of himself, and so comfortable with people.”

From that moment on, Austin seemed in control of his life. Back home in Opaskwayak, he started going to sweat lodges, and took a summer job working as a mentor for community youth. He hungered to become a soldier — he even convinced his mother to drive him to the United States to enlist there, if Canada’s forces wouldn’t take him — but poor eyesight put a halt to his application.

“He was looking to join the infantry, and didn’t want to sign up for anything else,” Lucy says. “The recruiter kept asking, ‘you know, there are so many different positions.’ And he said, ‘no, I want to be infantry.’”

Instead, Austin set about to make the best of his life. He joined an Indigenous youth leadership program in Peru, where he volunteered teaching English to kids and learning about the culture and traditional agricultural practices of local Indigenous people. When he came home, he took a job as a technician with Nisakapawino Forestry Management outside The Pas, where he soon earned the nickname “The Austinator” for his work ethic.

SUPPLIED

The opportunity to attend the Canadian Armed Forces’ Bold Eagle program for Indigenous youth put into focus what Austin (centre front, wearing glasses) wanted to pursue.

With the money from that job, he saved up for laser eye surgery. In the winter of 2021, he got his vision fixed and applied again to the Canadian Armed Forces. They asked him to go to a two-year training program; Austin declined. He wanted to go straight to the infantry.

So again he went back to work, this time with a forestry program in Portugal. Austin was excited to see Europe and his parents were over the moon: just like they’d dreamed, their eldest child was travelling the world and doing the things they never got to do.

“That’s what his dad says: ‘he lived a lifetime longer than me,’” Lucy says. “Even though it was scary to travel and do things, we always knew that if he was ever stuck, he could call me or his dad. We’ve always done whatever we could to help him.”

“As soon as he joined he felt like it was a family right away. It didn’t matter where they came from.”–Lucy Lathlin

Then everything changed. A few weeks after Austin got to Portugal, Russia invaded Ukraine. Lucy wasn’t following the war closely — “I have enough stressors in my life, and I get too emotional,” she says — so she was only mildly confused when Austin called to ask for the paperwork confirming his time in the Bold Eagle program. She asked why.

“Oh, no reason,” Austin replied.

A few days later, Austin called his father.

“Dad, I’m in Ukraine, and I’m joining the International Legion,” he said. “Can you tell mom?”

You have to tell her yourself, Adam replied, and handed the phone to Lucy.

She listened in shock as Austin explained his decision. He’d seen the refugees from Ukraine spilling into Portugal, he told her. He’d seen the exhausted faces of the women and children and read reports of civilians being killed. He couldn’t just sit there and watch. And what if the war spread to engulf the whole world? So he wanted to fight for his brothers and sisters too.

Lucy took a deep breath, held back the fear in her heart, and told him she was proud of him.

“I said, ‘every day I’m sending you my love and my hugs and my prayers, and sending you my prayers for all your brothers,’” she recalls. “As soon as he joined he felt like it was a family right away. It didn’t matter where they came from.”

For the next two days, Lucy wandered around the house in an anxious daze, feeling as if she couldn’t quite catch her breath. Then she called the rest of their big family, told them the news, and they began raising money to make sure Austin had the gear he needed to fight.

The fear still gripped her. It all seemed surreal. Yet deep down, she wasn’t surprised.

“That’s just the way he was,” she says. “He was always trying to step forward. It’s something he got from his dad. His dad always said, ‘when you’re scared of something, do it anyway. Be the first one. Nobody wants to go first, well I’m the person that will go first, just to break the ice.’ And that’s what Austin did a lot of the time.”

In the months after the close call in the Kharkiv region, Luka’s injuries healed and he returned to the front. He got a medal from the Ukrainian military. Austin, who had saved his life, did not, which the guys teased him about sometimes. Austin hated that, they laugh.

“He didn’t stand out and shout about himself,” Craig says. “He never had an ego about it.”

And Luka, who felt a debt he both wanted to repay — “Croatians are like, ‘I don’t want to owe you money, I don’t want to owe you a favour,’” he says — and dreaded ever having to, made a point of joining any mission Austin went on, just in case.

On May 24, 2023, one year to the day since Austin saved his life, Luka called his friend.

“The first thing (Austin) said when he picked up was, ‘I was about to call you also today,’” Luka says. “I was like, ‘why? You saved my ass, you’re not owing me any calls.’”

At that time, Austin was not with the legion. He’d left Ukraine in the fall of 2022, travelling back to Canada to rest. (Unlike Ukrainian soldiers, foreign fighters were able to break their contracts with the military and leave at any time, though Ukraine recently passed a law requiring them to serve at least six months before they quit.) His family held a feast to welcome him back, where an Opaskwayak band councillor gave a speech about how proud they were of his service, and pledged an even bigger feast the next time he came home.

SUPPLIED

Austin Lathlin-Bercier worked as a technician with Nisakapawino Forestry Management where he impressed with his strong work ethic. He longed for the opportunity to join an infantry unit.

Yet Austin’s heart was still with his brothers-in-arms, and in late summer 2023, after a sojourn travelling around Europe, he returned to Ukraine. By then, Bravo 2’s combat role had changed. For the first months of the war, they’d largely been tasked with reconnaissance; now, they had become a full-fledged trench assault unit. They’d also moved to a new front, out of the Kharkiv region and closer to the brutal battles around ruined Bakhmut.

This change suited Austin, who preferred, several of his fellow soldiers said, the adrenaline of dynamic firefights to the long days of waiting and holding positions that marked much of their previous service.

But by late 2023, Austin, like many soldiers, was frustrated with the institutional and battlefield chaos churning around him. Ukraine’s summer counteroffensive had fizzled out; many battles to stop Russian advances were costly and brutal. Austin thought about leaving, he told some of his comrades; he talked fondly about the idea of going home for Christmas.

Yet he didn’t go. Maybe he knew the guys needed him — and maybe he needed them, too.

“The reason for all of us (to stay) becomes not so much Ukraine, or the unit, but the people you want to fight with,” Craig says. “The legion can be terrible at times. We all stay because of each other. We have fun together. It’s hard to explain to a lot of civilians.”

Some soldiers grow closer to this new family than the old; some soldiers find it hard to talk to folks back home about what they’ve experienced. But Austin spoke to his mom almost every day. Several of his brothers-in-arms remember how he always made time to text or call her.

On some of those calls, Austin said something that struck Lucy as a bit strange.

“You know mom,” he said gently, on several occasions, “if something happens to me out here, they may not be able to get me home.”

Lucy, unsettled, tried to lighten the mood. “You have to come home,” she’d reply. “You still owe me money.”

Somewhere on his phone, Craig has a video of the last conversation he had with Austin. It was Nov. 11, 2023 — Remembrance Day in Canada — and they were headed out to an early-morning mission. Their goal was to seize a trench held by Russian forces.

The journey was tense. They slipped through minefields one by one, to avoid being a clustered target for the drones tracking their approach. (“You are always on camera out there,” Craig says. “Always.”) Somewhere ahead of Craig, over the undulating steppe land of Ukraine’s Donbas region, sharp bangs of exploding grenades split the air.

SUPPLIED

His friends knew Austin to have an unflappable spirit.

When Craig reached the rendezvous point, he found Austin waiting, cradling his weapon. The Canadian looked relaxed, but then again, he always did. Craig pulled out his phone to capture the moment; those blasts he heard, were they close?

“Yeah man, it was f—king close,” Austin said, with a grin.

They bumped fists and pressed on.

Austin was not supposed to be in the front on that mission. But unlike Ukrainian units, Bravo 2 operated on a purely volunteer basis: if guys didn’t want to go, they didn’t have to go. And that morning, a couple of guys who had been tapped for the team pulled out.

Their withdrawal put the mission in jeopardy: “four people can’t assault a position,” Craig says. So a team leader went around the base asking for volunteers; Austin was sitting with his roommate, an American who was his closest friend in Ukraine.

“Yeah, we’re coming,” Austin said, as casually as agreeing to go to lunch. Craig was relieved.

As they approached the Russian trench, the group took up their positions. Craig and his team were positioned low in a valley, preparing to rush the trench. Above them, Austin and his friend settled in to provide covering fire.

The firefight was long and intense. It seemed to be plateauing, Craig thought, and maybe they still had a chance to break through. Suddenly, the covering fire behind him fell quiet. He turned and shouted for more, but none came. With the battle now lost, the soldiers scrambled to pull back to a safer position; when they got there, one of them was missing.

“I just remember thinking, ‘Shit. Austin. It can’t be true. Austin doesn’t die.’”–Craig, fellow member of Brave 2

Austin Lathlin-Bercier had become the first Manitoban known to be killed in combat in Ukraine. He was 25 years old.

“At that point everything just stopped,” Craig says. “I just remember thinking, ‘Shit. Austin. It can’t be true. Austin doesn’t die.’”

And he looked at the valley from where they’d come, towards where Austin’s body lay a short distance from the Russian trench, and knew, in that moment, they wouldn’t be able to get him. At least, not for a very long time, and not until after a lot of hard fights.

News spread through the unit’s text group chats that someone had been killed on the mission. At the command post, Luka had just returned from picking up a crew of freshly arrived recruits, when he met an officer waiting at the door. He lit a cigarette and said what he was dreading.

“I f—king hope it’s not Native,” Luka said.

It’s Native, the officer confirmed.

In shock, Luka went inside the command post and demanded to see the video of the mission, taken from a drone watching high above. At least it was quick, he thought to himself, because Austin deserved that. When the video was done, he went outside, lay down in the dirt behind some bushes and for the next hour, he just cried.

Over the days that followed, Luka packed up Austin’s belongings and turned them over to the Canadian embassy in Kyiv. And he called Austin’s father, fulfilling a promise he’d made to his friend, remembering how he’d once made Austin promise to do the same.

As the unit struggled to comprehend the loss, a sense of unfinished business tainted their grief. Austin was the fourth soldier from Bravo 2 to be killed, but the first in the International Legion, they say, whose body they could not recover. It gnaws at them that he’s still out there, lying in the pockmarked no-man’s land now firmly under Russian control.

“It really hurts,” Craig says, meeting earlier this year in a Kharkiv café. “But I’ve spent a long time thinking about it. I think Austin was a professional, he was a really intelligent guy. If the roles were reversed, and if he could’ve told us there and then to do something or not to do something, I think he would have said ‘just don’t bother, because you’re going to get yourselves killed trying to get my body.’”

He pauses and takes a sip of raspberry tea.

“We’ll get him one day. As soon as we get there… we will bring him home.”

In the meantime, he likes to imagine his friend is still forging ahead with the mission.

“Austin’s still there, fighting,” Craig says. “His spirit will still be fighting the Russians right now, and he’s going to make it absolute hell for them to hold that position. He’s going to scare them at night, he’s going to walk around, he’s just going to terrorize them.”

What his brothers-in-arms want his friends, family and community back home to know is Austin knew what he was doing. He knew the risks and chose them. They talked about that all the time. And they want people to know that they loved him, a lot. To Luka, he was “the best of the best.” To Craig, he was “a real character.”

“But he was also a true warrior, a real fighting guy,” Craig adds. “And not just on the battlefield, but in life. If something was difficult, he wouldn’t just stop. He would keep fighting, physically and mentally. Whatever shit situation we were in, he wanted to make himself comfortable.”

SUPPLIED

Austin with a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. After focusing on reconnaissance early in the war, his company became a trench-assault unit.

At home in Manitoba, grief settled over the Lathin-Bercier family. The process of unravelling the paperwork around his death was agonizing. Six months after he was killed, they finally received his belongings from the Canadian Embassy; they arrived on Mother’s Day weekend, which to Lucy felt like a sign. They still are waiting for his death certificate. And they ache to get Austin home and lay him to rest on his Cree territory, with his family.

“I’m still hopeful one day,” Lucy says. “But for now I’m just taking this a step at a time.”

Yet there is also light. Because Lucy still feels Austin’s presence, all the time. One day, earlier this year, she was walking past a doctor’s office when she heard his voice whisper in her ear, telling her to “just go in.” So she made an appointment, where a doctor found breast cancer. They’d caught it early enough to remove it all; she is expected to fully recover.

“All because Austin whispered in my ear and I listened,” she says. “I know it was him.”

There is also some comfort for Lucy, in knowing her son. Because there’s a word that kept coming to mind, as I spoke to his mother and brothers-in-arms for this story. It felt like the wrong word, even obscene to use in a war, but nothing else quite fit either.

In all the stories comrades tell about Austin, he is relaxed, even joking; in the videos they took in the field, he’s always smiling. I ask Lucy about that, in one of our conversations. For all the horrors he witnessed in Ukraine, I suggest, it seemed as if Austin was happy.

Lucy’s eyes open wide in agreement; she nods emphatically.

“It is the right word,” she says. “It made him feel like he made a difference. Austin was always trying to help. When he went over there, it was like he had a purpose. He never knew what his purpose was.”

SUPPLIED

“Austin was always trying to help. When he went over there, it was like he had a purpose,” his mother Lucy said.

As the days passed, she began planning for a memorial for Austin, which they will hold on his birthday, Aug. 1. Some of his brothers-in-arms plan to be there, to show their love for him in person.

And she thought about what she and her husband wished for Austin on the day he was born. The way they dreamed for him to see the whole world, to make friends from all over, to have opportunities that don’t always come easy to a kid from a northern Manitoba First Nation.

“That’s what I wished for, and he made my dreams come true,” she says.

It’s then that she feels, for all the grief of Austin’s loss, a sort of peace in it all. After all, in a way it was as if he always knew what would happen. And if Lucy had known too, would she have tried to change it? When he first called from Ukraine to say he would be a soldier, would she have done it all differently, and demanded he come home?

“I’ve been thinking about that a lot,” she says. “But if I’d have changed my decision, and not supported it, what kind of life would he have led? I wouldn’t have changed it. I would have did everything the same. Because it made him happy. He was living his life, and that’s all I ever wanted. So I couldn’t hold anything back from him.”

Melissa Martin is the Free Press writer-at-large. She is currently on leave in Ukraine.

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large (currently on leave)

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.