GLADSTONE — “Democracy is… coming through a crack in the wall, on a visionary flood of alcohol,” sings Leonard Cohen.

My favourite Cohen tune plays on AM radio while I drive two hours from Winnipeg to visit a curious bar, Royal Canadian Legion 110, tucked in this town alongside the Yellowhead Highway. The veterans’ organization is a vital hub of civic life for the community of 900, acting as something in between a community centre, charity for veterans and other causes, and safe space to get buzzed and gamble.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS

Part of the appeal of local legions is the kitsch of the Union Jacks and quaint military lore, not to mention the $5 lagers.

I’m meeting Ernie Tester, president of the legion’s Manitoba Northwestern Ontario Command — which counts 17,000 members and covers 126 branches — at his hometown legion, situated on the town’s east-west main drag. I notice it’s given pride of place on Gladstone’s painted highway sign highlighting attractions to visitors.

For all the talk today of struggling and closing performing arts groups, venues, churches, media outlets and sports teams, I’m struck by the resilience of Canada’s seemingly antiquated veterans’ halls and clubs. The Army Navy Air Force Veterans in Canada (ANAF) has 74 branches across Canada, while the Royal Canadian Legion has a whopping 1,350, losing only a handful during the pandemic.

In urban centres, these scattered spaces are shrouded in rustic charm for the many non-vets who drop in for the cheap beer, bingo, Canadiana and shuffleboard. In small towns, they’re much more than a nostalgic curiosity, often playing an important role like Legion 110. Many legions in rural Manitoba also act as voting stations, creating scenes I imagine would have tickled Cohen. At a moment of rising political polarization, often expressed in tensions between rural and urban residents, I’m extra curious about these veterans’ organizations’ cultures.

These heady themes become a little hazier as I knock back a couple of Molson Canadians with Tester and his comrades at Legion 110 on a cool Saturday night in June. Tester graciously buys. Reverence for Canadian military history is, unsurprisingly, thick at this rural Manitoban branch of the veterans’ organization — almost awkwardly so for me, as someone who never outgrew my youthful anti-war idealism. Yousuf Karsh’s frowning Winston Churchill portrait stares me down as I try to answer someone’s question about my family connections to the armed forces. “Both my granddads fought in the Second World War,” I promise.

CONRAD SWEATMAN / FREE PRESS

Gladstone legion president Sylvia Hayward conducts

the meat draw, a staple at many veterans’ clubs.

Soon the mood feels light. During the meat draw, I meet Legion 110 president Sylvia Hayward, who is very sweet and very short. I snap some pictures of the gathering, and the Brit running the meat draw cracks a joke about me vetting models for the Sunshine Girl. When he remembers I’m with the “other guys,” he tells me that when he first arrived to Gladstone, his wife would inadvertently steal copies of the paper I represent. She believed the “free” in Free Press meant just what it said.

We have a quick bite at the Paris Café, a 100-year-old Chinese restaurant. After that, Tester and former legion president Nick Beavington give me a tour of the area. We cross the Whitemud River, passing the public pool with its sign acknowledging the legion’s largesse (a donation of $50,000), and exit town. We drive by a Hutterite colony, with its giant farmhouses and shiny new tractors servicing a collectivist way of life. Further down the road, we see Amish “horse-and-buggy people” tearing off their suspenders to splash in a pond. These scenes make Gladstone seem positively cosmopolitan by contrast. Tester tells me that when Amish families cart through Gladstone, they pull over for ‘pickups’ when a horse does its business on the town’s streets.

Gladstone proper, however, is not an Anabaptist stronghold. Its Anglican church closed recently, while the arrival of Filipino families in the past decade has grown Gladstone’s population of Catholics. Tester believes the legion to be among the best places for the town’s heterogeneous population to hobnob and mesh. “We’ve got a lot of Filipinos coming into our branch and Indigenous peoples,” he tells me. “We need different cultures involved in our legion.”

CONRAD SWEATMAN / FREE PRESS

Former Gladstone legion president Nick Beavington stands outside the gathering place vital to civic life in the small community.

I’m reminded of my most memorable Thanksgiving dinner last fall, which unfolded at Churchill’s Legion 227. A big number of the Arctic town’s diverse population showed up for the event, with free turkey and homemade pie for all. Naturally, as a tourist my perception was shortsighted. But coming from a city as socially partitioned as Winnipeg, I was impressed with how freely those gathered mingle with one another. Randomly, I sat with the U.S. Consul to Winnipeg, there to meet Churchill’s mayor. The next day the mayor, who with his wife runs the Seaport Hotel where I stayed, sat beside me as his wife shuttled us to the airport.

The morally flawed G.K. Chesterton, a fan of the Royal British Legion, remarked more than a hundred years ago that small-town people know more of humanity’s “fierce variety and uncompromising divergences,” because in “a large community, we can choose our companions. In a small community, our companions are chosen for us.” This is a contrarian vision of diversity, broadly seen as a metropolitan virtue. Relatedly, in the neighbourhood pub — in contrast to the high-minded London social club — Chesterton saw an arena where common people in all their motley variety could come together in “clamorous accord… a fellowship of beer and board.”

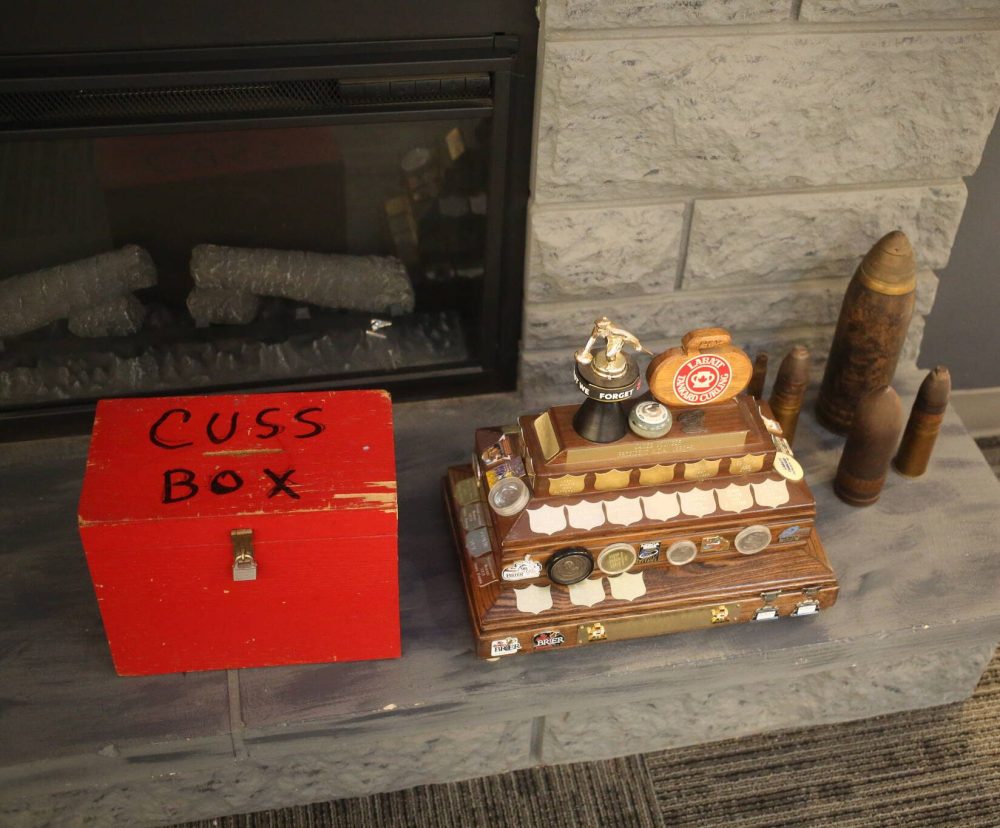

CONRAD SWEATMAN / FREE PRESS

Hats off and watch your language, please.

While Chesterton may be trolling a little here, in these lines I recognize something of my experiences of Canada’s legions. Still, I remind myself that in their rich 100-year history, there are moments when certain legions have acted like a small town also in the parochial sense, leery of outsiders. Few will be surprised to learn some branches could be partial to the repressive anti-communist and anti-Japanese sentiments that infected so much of Canadian society in the decades surrounding the Second World War.

More than a little has changed since then, including the organization opening membership to non-vets in 1998. This transition has paved the way for a legion culture that better reflects Canada’s social fabric, but hasn’t been entirely smooth. Some will recall how the organization found itself in hot water a few years ago, after a security guard at a legion in Tignish, P.E.I., told a Sikh patron to take off his turban. The local’s president quickly apologized — publicly clarifying that religious headwear is exempt from the legion’s well-known no-hat rule — and the affair seemed to blow over within a few weeks. The president’s response signalled the legion’s style of nationalism is making room for Canadian multiculturalism. But is this a contradiction in terms?

SUPPLIED

Today’s legions and ANAF halls, such as Club 60 in Osborne Village, attract a broad cross section of clientele.

A more divisive figure in urban Royal Canadian Legions, comically, is that contemporary dandy known as the “hipster.” The charmingly kitsch medallion carpets, the $5 lagers, the Union Jacks and quaint military lore — it’s easy to see the appeal for alt-kids with a taste for irony and cheap booze. The increase in countercultural types among clubs’ regulars has met with mixed reactions from old-stock legionnaires, judging from this trend’s media coverage. It’s not hard to see how a perceived influx of peaceniks with newfangled haircuts and pronouns could make some of the old-timers grumpy, even while others surely welcome their new shuffleboard opponents.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS

Military mementoes are as much a part of the fabric of legion halls as cheap beer.

Whether it’s the “hipster incursion” or for other reasons, there’s a lingering concern the organization has grown disconnected from its traditional membership, veterans. Even Tester — who embraces an eclectic vision for what the legion is and could be — is sensitive to this. “We have to support young veterans, work with young veterans, communicate with young veterans and welcome them,” he told Global News in 2023. “A lot of the veterans I talked to, and some of them are friends of mine, personal friends of mine, they don’t feel welcome here, (in) a legion,” Dominic Jones, president of Legion West Kildonan Branch 30, told Global in the same story. Nujma Bond, a national spokesperson for the legions, strikes a more conciliatory note. “An ongoing focus is also making sure all legion members and guests feel welcome, no matter their military or personal backgrounds,” she says in an email to me, but adds, “at the root of all we do is serving our veterans, their families and communities.” This support goes well beyond a welcome table at their many bars across Canada, and includes financial assistance, programs for PTSD and homeless veterans, and much more.

Club 60, where I’m something of a regular, in Winnipeg’s trendy Osborne Village has some of the same sticky dynamics I’ve been describing. While belonging to ANAF, a veterans’ organization separate from the legion but with a similar purpose and culture, Club 60 is known by everyone in my peer group as “the Osborne legion” — a confusion that might annoy its members. I regularly drop into Club 60 with my friend, an artist and Indigenous woman. She gets a kick out of the hats-off etiquette and lingers on the Second World War lore decorating the walls. Her pal reminds me of the large number of Indigenous people, like Tommy Prince, who fought overseas from 1939-45. These vets returned to a Canada that ignored their sacrifices and denied them the benefits to which they were entitled. My artist friend talks admiringly nevertheless about those, Indigenous and otherwise, who risked their lives to fight a genocidal, imperialist regime like the Third Reich.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS

Second World War lore decorates the walls at the ANAF in Osborne Village.

Certain activists I know who frequent Club 60 are more militant in their anti-military stance. They may not even recognize Canada’s national legitimacy and likely roll their eyes at the yellowing photos of British Royals on the walls. But the local’s nationalist trappings mostly fade into the background. When political conversations arise as they do from time to time, I’ve seen only a couple of sour moments between people who seem to agree on little beyond the fact that fighting the Nazis was a just cause. The contests unfold around the pool table and by subtler means. Recently at Club 60, an 80-year-old man approached my friend group to shake our hands. Turns out he was less interested in meeting us than judging who had the firmest handshake. “This guy’s got a real strong one!” he announced about my tallest friend. “He’s handsome too!” We all laughed. And with that he got up to dance, because that’s one of the nifty things ANAFs and legions are for.

Reflecting on ANAF 60’s eclecticism, bar manager Anders Erickson says, “We try to be welcoming to everyone. People 18 to 80 come… It feels like not just a bar, but a community.”

I’m brought back to the questions that first got me thinking, and not just drinking, at these bars.

“We try to be welcoming to everyone. People 18 to 80 come… It feels like not just a bar, but a community.”–Anders Erickson

In Robert Putnam’s classic Bowling Alone, the sociologist sees bowling leagues’ fading popularity as emblematic of the decline in American (and by extension, North American) community and civic engagement. “Americans today are far less likely to participate in community meetings, join local organizations, attend church, vote, contribute to charities or fulfil other civic responsibilities than we were just a few decades ago,” he wrote in 2001. “We are less likely to know our neighbours, to invite friends home, to go on picnics or hang out in bars, to belong to trade unions and professional associations or simply to spend time chatting with acquaintances.” The resulting loss not only of bonding within social groups — but bridging across them — has taken a heavy toll on individual well-being and the health of democracy.

Common sense leads us to surmise that more and more Canadians are “bowling alone.” The pandemic’s temporary replacement of face-to-face interaction by Zoom meetings, online pseudo-communities and hours more of Netflix, PlayStation and Internet memes has turned out to be enduring. People just aren’t returning in the same numbers to the performing arts, religious sanctuaries, sports games and many other sites of social gathering underpinning public life. Genuine community is being overshadowed by online networks, which are both lonelier and more cruelly tribal. Judging by the rise in Canada of political polarization, all this shouldn’t be shrugged off as the price of “innovation” or necessary change: it seems symptomatic of a weakening civic culture. We should be worried about the future of our democracy.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS

Shane McKenzie (from left), Brittany Roginson and Aaron Nolin enjoy a drink at ANAF’s Club 60.

I wonder whether the organic culture of Canada’s legions and ANAFs — negative images perhaps of the declining bowling league — might have something to teach some of us about the possibility of civic revival. These organizations have proven comparatively resilient while so many other gathering spaces struggle “post-pandemic,” and surprisingly effective at attracting a clientele that cuts across cultural and class lines. This isn’t to pretend that more rounds of beer and pool matches in a shared space can make fast friends of the different demographics who patronize these bars, between rural and urban, blue-collar and white-collar, vaccinated and non-vaccinated, conservative and progressive, those waving the Maple Leaf and other flags, and so on. No matter how philanthropic and community-minded, nearly all bars are also by their very nature in the business of catering to habitual drinking and gambling; fuel for loneliness and conflict as much as fraternity.

But if there is a promising future for democracy in Canada, I can’t imagine it will be a polished affair narrowly among Laurentian elites. It will be as scrappy as it is pluralistic, it will empower everyday people from all walks of life as participants and its manner of speech will often be colourful, politically incorrect, banter-like and restless. It will flood through the cracks.

Is it naive to hope we can find inspiration for democratic renewal in the contradictory cultures of some of our neighbourhood and small-town bars, in our strangely vital legions and ANAFs? Probably a little, but the beers are refreshingly cheap, they have most the old-school bar games our parents and grandparents played — and you might find yourself in “clamorous accord” with someone flying a different flag than you.

Conrad Sweatman is a Winnipeg writer.