When fresh-faced students flock to the University of Winnipeg campus in a few weeks for their first taste of post-secondary education, for the first time in nearly half a century they will not have the opportunity during their undergraduate degrees to learn about what’s happening in their own heads from Hinton Bradbury, a gifted professor of psychology who joined the faculty in 1974.

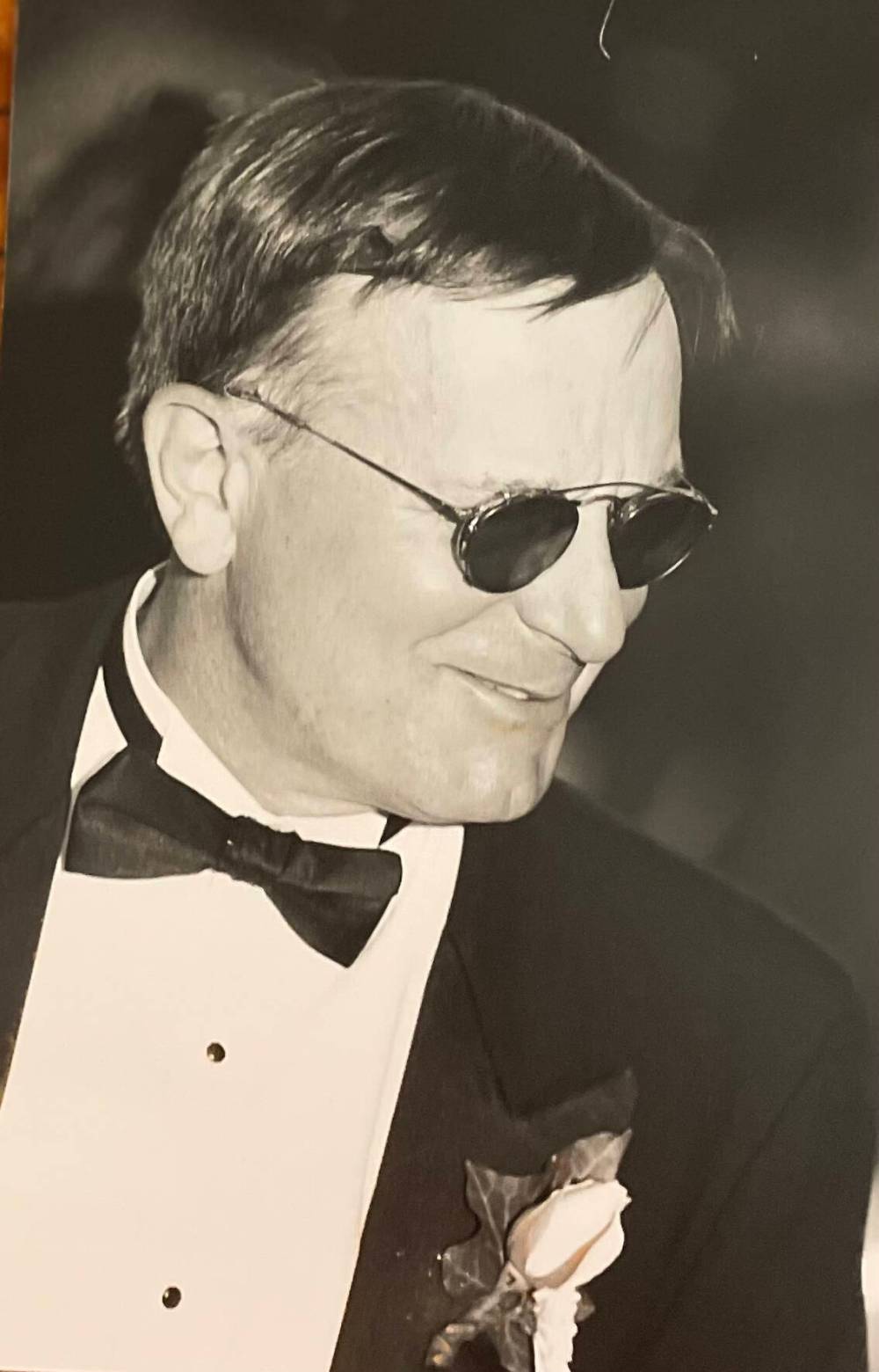

Bradbury, who died in June at the age of 82 after a brief illness, was a devoted Freudian scholar and developmental psychologist renowned for his capacity for toughness and kindness, clean-cut erudition and folksy charm, and a staunch attitude of professionalism complemented by a readily deployed wit.

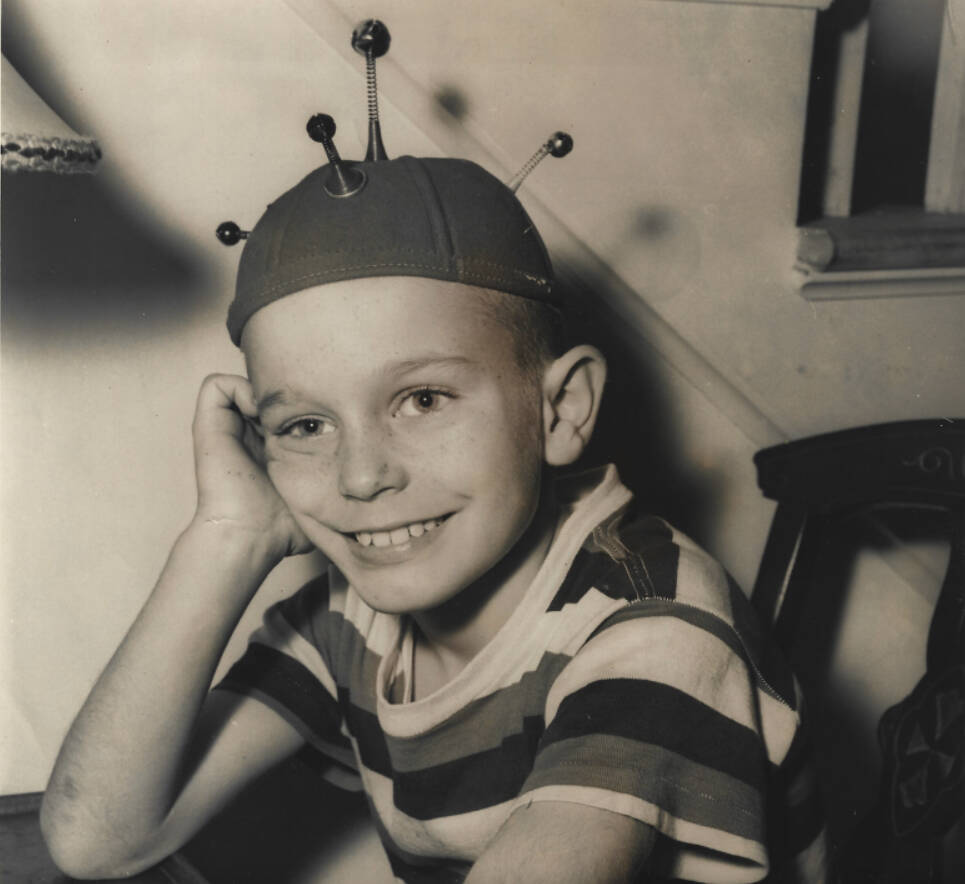

Born on Aug. 15, 1941, in the mid-sized Georgia town of Quitman, Bradbury was the only child of journalist Betty Garnet and photographer Osceola Hinton Bradbury. The family spent its first years in Quitman, where young Bradbury was doted on and frequently featured in his father’s images, posing next to muzzled bears and lifeless snakes shot in the Georgia wilderness.

After his parents’ separation, Bradbury and his mother moved to Miami, where his mother married Tony Garnet, the head of the photography department at the Miami Herald, where she became editor of the paper’s weekly magazine.

In 1960, Garnet joined the Miami News, and the couple soon hosted a swanky party to celebrate the paper’s 1959 Pulitzer citation for national reporting by Howard Van Smith. Bradbury, who worked throughout high school as a Herald press boy, would later recount to his daughter that the medallion ended up in the swimming pool.

A cocktail of southern charm swirling with cosmopolitan intellectualism, Bradbury was a precocious student at Coral Gables Senior High, where he swam competitively and played clarinet in the marching band. Upon graduation, he enrolled as an English major at the University of Miami, where he began two lifelong love affairs — with the romantic poet John Keats and with the university’s vaunted Hurricanes football team.

It might surprise his psychology students to learn that Bradbury’s first academic posting was as an English instructor in his mid-20s at Miami-Dade Junior College, a position he held while completing his master’s thesis on Keats at the university. At Miami-Dade, he met his first wife, Gail Jordan.

But Bradbury soon refocused his efforts to psychology, taking additional courses in order to apply for acceptance to a doctoral program. His approach to selecting his next place of study is so silly and straightforward that it almost seems logical.

“He hadn’t seen snow before, so he wanted to go where he could,” says his wife, Diana Bradbury, whom he married in 1991. Thanks to the hierarchy of alphabetical order, he selected the University of Alberta, and in 1965, Bradbury and Jordan moved to Edmonton, where they kept horses, bred St. Bernards and had three daughters, Kirsten, Jessica and Clara.

In 1974, Bradbury was hired by the University of Winnipeg as assistant professor and as chair of the department of psychology. At the U of W, the sharp-dressed Bradbury’s aim was to establish a reputation for excellence in both teaching and research.

“He said the most important decision any department can make is hiring,” says social psychology professor Beverley Fehr, who was Bradbury’s student before he hired her as a colleague in 1986.

Bradbury’s research focused on the principle of transitivity in children’s novelty preferences. As a lecturer, his most popular courses included Advanced Freudian Personality Theory, Freudian Analysis of Film and an intensive small-group seminar on the Viennese father of psychoanalysis that “gained an almost mythic reputation for being both exceptionally difficult and life-changing” according to his daughters.

“The first time I met Hinton was in 1976 when I was enrolled in his introductory psychology course,” recalls Fehr. “I was from a very small town and was intimidated to go to university, and then I met this professor who was so unbelievably articulate, so incredibly intelligent, so very funny and so very kind.”

Fehr served on the hiring committee with Bradbury for years, and says it was rare for any candidate to turn down a position after Bradbury gave them his pitch. When new faculty members arrived, Bradbury would throw one of his legendary house parties, preparing “first-class” ribs with recipes gleaned from his and Diana’s frequent trips to New Orleans and showing up to their doorsteps with cheesecakes from Baked Expectations once they’d settled in.

Bradbury met Diana in the 1980s when she was an aerobics instructor at the YMHA on Hargrave Street.

To Diana, who recently retired from a 30-year career as a middle-years teacher, Bradbury was the hot guy playing racquetball. Their first verbal exchange came when she and a friend entered the court area to start a game of their own.

“His only words to me were, ‘You girls need to wear eye guards.’’’ Years later, they started to date, with Bradbury cutting tiny hearts out and leaving them on Diana’s windshield as a crafty form of courtship. Their first drink was shared at Mother Tucker’s, not far from the athletic club.

A winning racquetball player into his 70s, Bradbury also volunteered on Wednesdays and Saturdays to teach the game to kids and teenagers, who responded well to his educational style.

“He was a great teacher, and a very youthful guy. Much like one of the kids in a lot of ways,” remembers Ari Posner, a Toronto-based composer who trained with Bradbury in the early 1980s.

“The most classic piece of advice he gave us was that there was no mercy when you’re playing,” says Posner. “He would come up with these imaginary situations: what if your opponent’s girlfriend or grandmother is in the crowd and you’re up 12-1? Do you take it easy on him? No.”

On his own time, and sometimes his own dime, he would organize trips to Grand Forks, N.D., for the group to participate in youth tournaments.

“We used to joke around that we were a psychological experiment to him,” Posner says.

But anybody who knew Bradbury came to understand that he simply had an insatiable desire to teach.

Almost as powerful was his yearning for self-improvement and skill development. When he moved to Winnipeg, Bradbury bought a three-storey house on Walnut Street that had fallen into disrepair as a rooming house. He did all the handiwork himself, using salvaged materials wherever possible, and did the same with several other houses on the block.

Bradbury also took painstaking efforts to build his daughters a handcrafted dollhouse, complete with hand-chipped cedar shingles and Victorian detailing.

“His energy level was phenomenal,” says his daughter Jessica Coulbury, who says her father encouraged spirited conversation and critical thinking wherever he went.

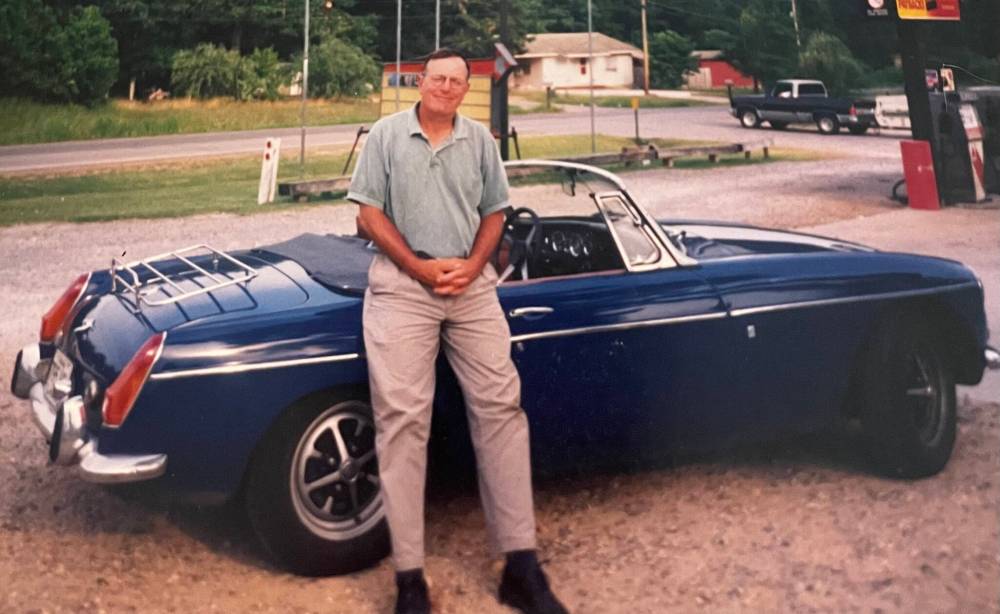

In his spare time, he played hearts and billiards, kept up with the Hurricanes, enjoyed a daily beer no earlier than 5 p.m. and devoured both the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, often choosing to read them from the comfort of his bathtub. He was a fan of British touring convertibles, driving a midnight blue 1974 MGB before trading up for a cream-white 1960 MGA.

Meanwhile, he helped found the Children’s Museum, taught classes for inmates at the Stony Mountain Institution and was for years an instructor for the provincial high school enrichment program, which gives teenagers a taste of university-level education.

Bradbury was affectionately known as Mr. Walnut Street, frequently throwing welcoming parties for new residents on their Wolseley block and making friends not only with the adults but their kids as well. Once, Diana didn’t know where he’d gone, it turned out he was the oldest participant at a children’s tea party.

“Once he built a deck for a woman down the street just because she needed one,” she adds.

He also continued to build dollhouses for neighbourhood children and for the children of friends. His first dollhouse, built in 1976, is now in his daughter Kirsten’s office, where she works as a clinical child psychologist.

Despite his children and grandchildren living in the United States, Bradbury was deeply involved in their lives, often driving with Diana to visit them because he preferred not to fly.

In the tradition of his mother, Bradbury could never resist the opportunity to host, and always set an impeccable table covered with favourite foods like gumbo, collard greens, raw oysters, ribs and lemon meringue pie. He’d host neighbours and colleagues, and each year would invite his Freud seminar group for an end-of-school bash at his house.

“He could be very serious, but he knew how to have a good time,” his daughters wrote of their father, who had six grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. “He was awesome.”

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman

Reporter

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.