The countdown to kindergarten is accompanied by a series of surprise presents — not unlike an Advent calendar — in the Silvers’ home in The Maples.

Tannis Silver wrapped up seven bundles of school supplies and labelled each one with a number in a bid to drum up excitement in the days leading up to her four-year-old’s first-ever day of class.

Ben’s week of surprises? Sparkly glue sticks, hamburger-shaped erasers and a fuzzy, rainbow-coloured notebook, among other kid-friendly stationery.

“He’s not entirely sure how to feel about it,” said Silver, noting her “mom’s intuition” points to both the newness of school and the limited social interactions her youngest — who was born just months before COVID-19 was detected in Manitoba — had as an infant.

“We haven’t done a ton of activities with him the way I did with the older two. We didn’t go to toddler gym or baby mamas’ groups when he was very young because, of course, all those things were shut down for the pandemic, and then when they started up again we were still nervous about going out, and in the habit of staying home.”

Silver recalled the horizon of kindergarten was a positive motivator for her other, now-Grades 3 and 5 children to learn to wash their hands independently and complete other basic tasks. For her third, it’s a source of apprehension.

Ready or not, Ben is about to become one of 15,000 fresh-faced youngsters entering the public school system across the province.

More children are showing up to kindergarten without being fully potty trained, knowing how to share with others and meeting early development milestones.

That’s according to the first study of school readiness in Manitoba in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kindergarten teachers collect data on the province’s youngest learners during the latter half of the school year via the Early Development Instrument, an internationally renowned reporting tool created by the Offord Centre for Child Studies at McMaster University in Hamilton.

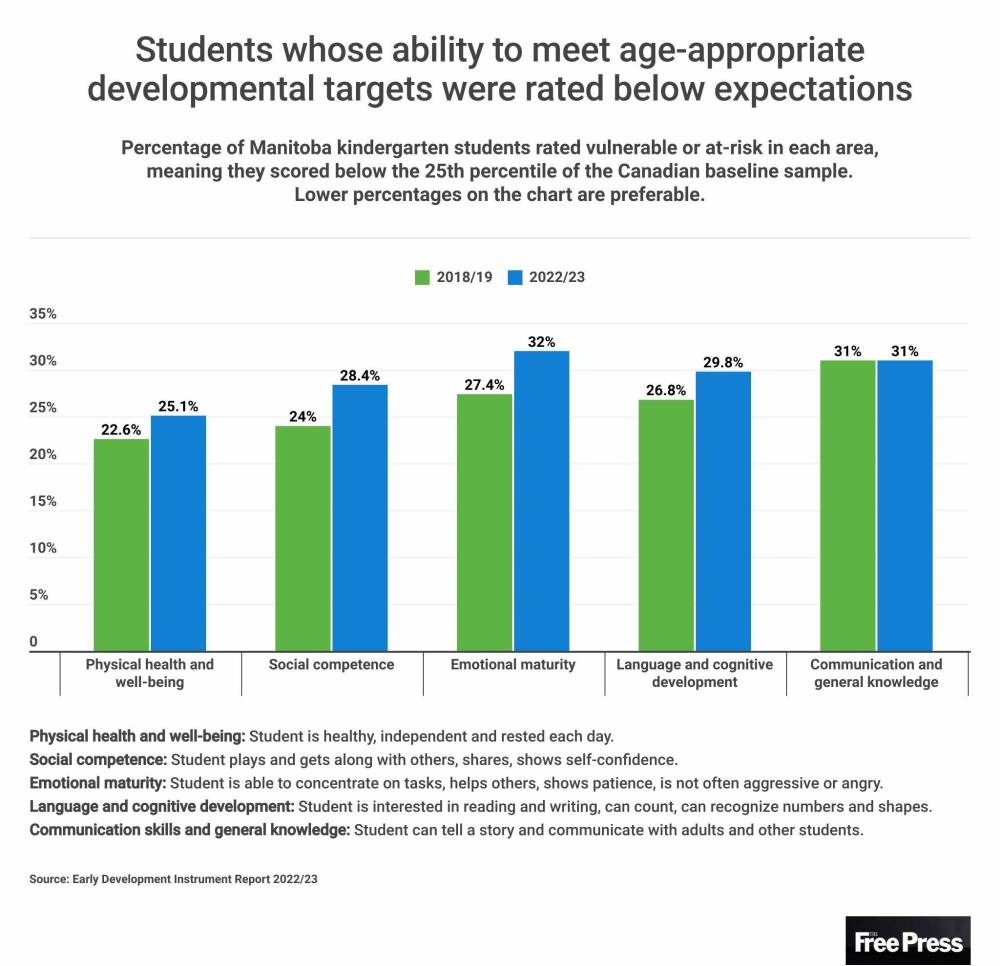

The tool assesses five-year-olds in five categories: physical health; social competence; emotional maturity; language and cognitive development; and communication skills and general knowledge.

The percentage of local students deemed “vulnerable” — children who score below the 10th percentile of the national baseline sample — grew in all five categories between 2018-2019 and 2022-2023.

“A slightly higher percentage of children in this cohort than earlier cohorts is not quite developmentally where they should be for their age,” said Magdalena Janus, a professor and researcher at the Offord Centre and co-developer of the EDI.

Janus noted some aspects of children’s behaviour, including aggressive outbursts, are impacted by “social learning,” meaning they come to understand what is and is not appropriate by interacting with peers.

The most significant slide happened in students’ abilities to concentrate on tasks, help others, show patience and regulate their emotions and aggression. The drop in boys’ readiness is marginally greater than the one between the pre-pandemic and mid-pandemic cohorts of girls.

“I am allowing more stuffies to come to school — security stuffies — I never say no to that, within reason. We have rules, but there are some kids that I would say need (the comfort of a plush animal). It’s just part of our classroom now,” said Kenny Benson or “Mr. B,” a veteran kindergarten teacher at St. George School in St. Vital.

Benson’s general observations about pandemic toddlers and preschoolers is that they’re more hesitant to leave their parents’ sides in the mornings, their attention spans are shorter and sharing is a particularly difficult task for them.

His response has included patience, switching up lessons more frequently and taking multiple balls outside for students to play with to reduce tantrums.

There’s a greater need to repeat basic tasks, such as practising how to line up or flip through a book and scan its contents from left to right, Benson said, adding that takes time, so he’s grateful he can spend all day, every day with his students for 10 months.

Growing student needs in early years, as well as demand for child-care spaces and a desire for equality across the Louis Riel School Division, contributed to the board of trustees’ decision to make full-day kindergarten universal this year. The Evergreen School Division is doing the same at its facilities in and around Gimli.

Until recently, Manitoba collected EDI data every other year. The province is now submitting results to the Offord Centre every three years, so Janus said it will take a while before her team can make sense of any real trends.

“We don’t know whether it’s a blip, whether it’s something that just occurred for these young children because they had less opportunity to interact socially,” Janus said. “Young children are very resilient — I don’t want to dismiss (that).”

While cautioning against panic, the researcher said the latest data should prompt schools to keep a “very watchful eye” on local development indicators and make programming adjustments accordingly.

“The EDI vulnerabilities are highly predictive of later academic success,” she added.

“If we have slightly higher percentages of children who are vulnerable in language and cognitive development in kindergarten, it’s quite likely that there will be slightly higher percentages of these children struggling with aspects of reading and mathematics in Grade 3 or 4, but that doesn’t mean that has to happen.”

An online survey of 100 kindergarten teachers conducted by the Ontario Institute for the Study of Education found that students are struggling with writing names, learning letter sounds and reading as they enter K-12 in a post-pandemic world.

Self-regulation, collaboration and social problem-solving are among early years educators’ top concerns, according to the findings published in the International Journal of Early Years Education in June.

As participants confront the realities of socio-economic development and academic gaps, they reported feeling compelled to choose between facilitating play and direct instruction.

Sheri-Lynn Skwarchuk, a trained school psychologist, said both areas can be worked on at once with an “all-hands-on-deck” approach that involves early childhood educators, teachers, parents and other adults in kids’ lives.

“It’s not anybody’s fault, and you can’t go faster,” said Skwarchuk, an education professor and director of developmental studies at the University of Winnipeg.

“Development is not linear. It’s up and down and it just depends on quality exposure and interaction.”

Skwarchuk created ToyBox Manitoba, an online platform with free literacy, numeracy and wellness activities targeted at children age eight and younger, as an entry point to support development.

The pandemic fallout has only reinforced her determination to share tips with parents on how to prepare students for school and socialization, which she said can be as simple as asking youngsters about their interests and encouraging their creativity.

It’s one of the final days of August and the smell of fresh paint, one of many summer-break upgrades at Brooklands School, lingers on the first floor as school staff ready themselves for the return of students.

Physical upgrades, including sprucing up a kindergarten classroom’s walls and deep-cleaning cubbies, are but one element of prep for the Class of 2037.

Teachers have been reaching out to families since the spring via orientations, summer enrichment programming and newsletters with age-appropriate learning activities. Teacher-student-parent conferences are scheduled for this week.

Principal Samantha Amaral said there’s been a growing trend of parents and guardians, especially those who are new to the school community in northwest Winnipeg, disclosing their personal anxieties.

Virus-related worries appear to have snowballed to encompass everything related to a student’s life inside and outside the school’s front doors.

“It’s just an all-over fear. Some people saw loved ones not make it through COVID, so now they just hold on a little bit tighter,” Amaral said, noting the school has been rebuilding trust with families since restrictions eased and once again allowed for “Cookies and Coffee” on Tuesday afternoons and other social events.

One concern that came up multiple times during Brooklands’ kindergarten information night on May 14 was potty training. It’s a challenge that has been on the rise in the building and St. James-Assiniboia School Division, generally.

“There are lots of accidents. The parents that are sending them in Pull-Ups (training pants) sometimes say, ‘We’ve tried, but this is just in case,’ or ‘We’ve tried and it’s not working,’ or they’ll send them in underwear and with a change of clothes because they know it’s going to happen,” Amaral said.

She said the issue is now affecting roughly a quarter of all kindergartners.

Division-level EDI data indicates more students are arriving to classes tired, late, hungry, under- and over-dressed, with co-ordination challenges and sucking on their thumbs. The student population showing hyperactive and inattentive behaviour is also growing.

Amaral said there’s been a notable learning curve around patience and instant gratification for new students, many of whom spent significant periods in front of screens amid stay-at-home directives between 2020 and 2022.

Students may be increasingly reliant on typing, but handwriting is a fundamental skill that Mercége Martins — who said she has been fielding more inquiries from parents interested in nursery and kindergarten prep in recent years — emphasizes in her tutoring.

“Children need to learn basic pencil skills, concentrating, sitting still, listening — all of these study skills to succeed,” said Martins, a certified teacher who owns a Kumon learning centre franchise in River Heights.

Kindergarten teachers across SJASD are spending more time using manipulative tools such as tweezers and squirt bottles to build arm strength so students can hold writing utensils properly, said Deidre Sagert, an early years support teacher in the Winnipeg division.

Manitoba Education’s kindergarten curriculum touts hands-on exploration and play-based learning about colours, the life cycle or trees and patterns. Students learn about everything from traffic safety to how to count to 30.

Sagert noted that socio-emotional goals are not spelled out as clearly as traditional academic markers, so she and her classroom-based colleagues are becoming more interdisciplinary to address everything from heightened impatience to “big emotions.”

That might look like reading a classroom book about sharing or friendship and then asking students to write a response, she said.

While Sagert said more kindergartners are presenting with limited fine-motor skills and mistakenly using “me” instead of “I” in sentences, she — along with other teachers — is hesitant to categorize the trend as a dip in “school readiness.”

“We’re ready for your children, regardless of how they come to us,” she said.

“We’re happy that they’ve walked through our doors. We’re going to welcome them and we’re going to take them where they are at, and our job is to move them forward.”

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Early Development Instrument report

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., Maggie was an intern at the Free Press twice while earning her degree at Ryerson’s School of Journalism (now Toronto Metropolitan University) before joining the newsroom as a reporter in 2019. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.