The second great war of the 20th century started slowly on the Western Front, where it was derisively known as the “Phoney War.”

But the situation was dire by spring 1940. France had surrendered to German forces and British troops had been chased off the continent at Dunkirk, France.

Canada, which joined the war effort days after Germany’s Sept. 1, 1939, invasion of Poland, made a commitment to supply more troops to aid its exhausted allies. In May 1940, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was authorized.

One of the regiments in the new division was the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, a legendary fighting unit dubbed the Little Black Devils with roots tracing back to 1885’s North-West Resistance and the Battle of Fish Creek.

The Rifles’ Second World War story started in July 1940 when recruiting began. About 70 per cent of enlistees were teens, many of whom were underage, or men in their early 20s. Many were the sons of First World War veterans; so, they were, in fact, the 20th century’s first generation of Baby Boomers.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

Soldiers debrief after a day patrol in Normandy on June 12. The Rifles continued to face hostilities in the days after D-Day.

Canadian war artist Alex Colville commented on that harsh reality. “I was born in 1920. This was the year in which most of the Canadians killed in the Second World War were born,” he wrote.

The Second World War, as we are sadly reminded of when visiting Canadian battlefield cemeteries, was a young man’s war.

The recruits began their training at Camp Shilo in western Manitoba and, three months later, were transferred to the 3rd Division’s miserable Debert Camp in Nova Scotia. In September 1941, the 36 officers and 860 other ranks of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles were deployed to England.

In August 1943, after two years marching around the south coast of England and, as soldiers do, getting into trouble, the regiment was transferred to the Combined Operations Training Centre at Inveraray, Scotland. The 3rd Division began training to be Canada’s spearhead of the long anticipated invasion of occupied France.

As the Royal Winnipeg Rifles’ War Diary entry of June 5, 1944, stated: “The sea was rough, and the landings look difficult, but the operation was on!”

War Stories

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles had an active association in Winnipeg and British Columbia after the Second World War. It continued to produce the Devils’ Blast, a publication the regiment had started during the war. It featured former soldiers’ stories from the Second World War as well as the First World War.

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles had an active association in Winnipeg and British Columbia after the Second World War. It continued to produce the Devils’ Blast, a publication the regiment had started during the war. It featured former soldiers’ stories from the Second World War as well as the First World War.

Those stories, along with letters and memoirs, are archived at the Royal Winnipeg Rifles Museum, located at the Minto Armoury.

Rifleman Jim Parks, 99, who enlisted at 15 years of age, is the Royal Winnipeg Rifles’ last surviving D-Day veteran. Several others quoted in the story enjoyed long lives upon their return from service.

Jack Hamilton: died in 2017

Jake Miller: 2000

Rod Beattie: 1983

Jack McLean: 2010

Phil Gower: 1956

Jim Bage: 2013

Tony Hubert: 2007

Ed King: 2001

Sotheby (Sub) Ketchen: 1984

Lockhart (Lockie) Fulton: 2005

Rupert Fultz: 1988

The next day, 800-plus men and officers of the Rifles were the first British Commonwealth soldiers to land on the Normandy beach code-named Juno. The destruction of Nazi evil in Western Europe had begun.

As their landing craft neared the shore of Juno Beach, the ramps went down. They were ready to go and every man learned that pure dumb luck determined whether they lived or died in those first moments of battle.

Every memoir of the Little Black Devils D-Day soldiers, found in the archives of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles Museum, tells similar tales of carnage, chaos and courage.

“I was the second man in our section,” Brandon’s Jack Hamilton wrote in his emotional memoir, “and the lad in front of me, Rifleman Philip Genaille, took a burst of machine gun fire in his stomach, while I wasn’t touched by that burst.”

Hamilton was almost immediately hit by shrapnel when he stepped on the sand and knocked unconscious. After regaining consciousness, he dressed his wound and made it off the beach. He wrote that he saw dead Canadians lying in a field of poppies.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

Members of the Winnipeg Rifles relax in the days prior to the D-Day invasion.

It reminded him of John McCrae’s First World War poem he learned in school: “‘In Flanders Fields, the poppies blow / Between the crosses row on row.’ That certainly struck me, seeing the Canadians lying dead amongst the red poppies blowing in the wind.”

Although fearing for their own lives, the riflemen did not hesitate to help their wounded friends. Jake Miller was wounded by a German sniper and then a bomb blast but, upon hearing Lt. Rod Beattie cry for help, Miller crawled back into the surf and tried to pull him to safety, but didn’t have the strength.

Sgt. Bill Welch came to his help and picked up Beattie, who was paralyzed from a bullet to the spine, and carried him to safety.

Rifleman Jim Parks, who enlisted at 15 and now at 99 years of age is the Royal Winnipeg Rifles’ last surviving D-Day veteran, also helped pull the wounded out of the water. After yanking his friend Bill Martin to safety behind a pillbox, Parks recalled, “Martin said he felt cold, and I held him and comforted him for a while until he passed away.” Parks had a chance to meet Martin’s parents after the war and told them how Bill had died.

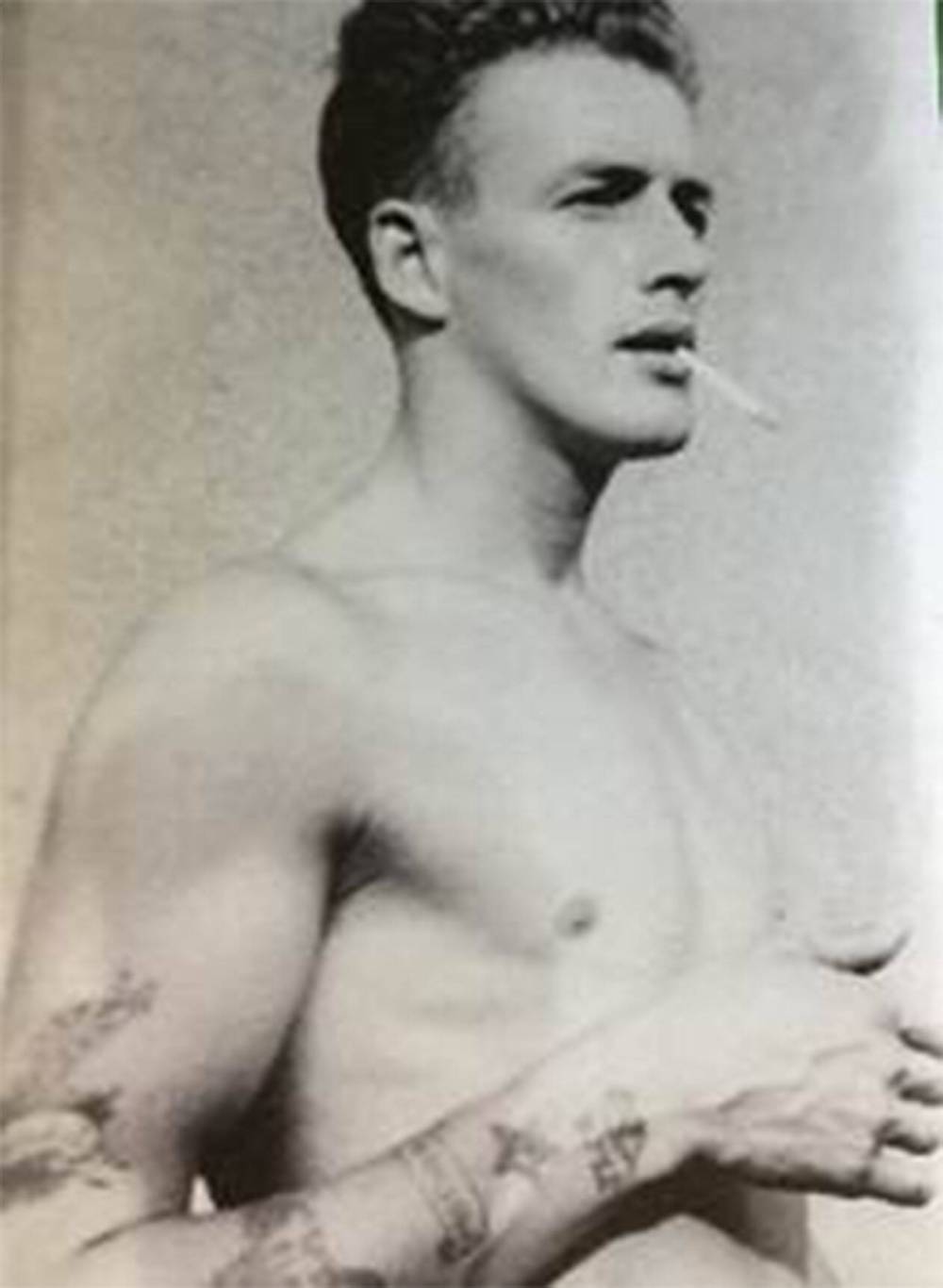

SUPPLIED

RWR Rifleman Jim Parks, c. 1943.

Canadian Press correspondent Ross Munro, author of the 1945 book Gauntlet to Overlord, described the day as follows: “Bloody fighting raged all along the beach… after a long struggle, which was bitter and savage… the Winnipegs broke through the open country behind the beach.”

It was a hard day for the Little Black Devils, but nevertheless a proud one.

“The Battalion during this day, D-6 June ’44, not one man flinched from his task, no matter how tough it was — not one officer failed to display courage and energy and a degree of gallantry,” the Rifles’ war diarist wrote. “It is thought that the Little Black Devils, by this success, has managed to maintain the tradition set by former members. Casualties for the day exceeded 130.”

According to the Canadian Virtual War Museum website, 35 Little Black Devils were killed or died of wounds received on June 6, 1944.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

Infantrymen of The Royal Winnipeg Rifles in Landing Craft Assault (LCAs) en route to land at Courseulles-sur-Mer, France, 6 June 1944.

One might have hoped the D-Day soldiers would have been taken out of the line. But this was not to be. One could say the Little Black Devils’ D-Day lasted 30 days. The unwashed, tired, hungry soldiers of the depleted regiment were continuously in battle and watched their friends be wounded and die.

June 7 was quiet but on June 8, D-Day plus three days, the inevitable German counterattack came. By the end of the third day, 131 of the Little Black Devils who landed on D-Day were dead, hundreds more wounded and many captured.

“I’m not sure but I think only one or two besides myself survived the war. Most of my friends were dead by D-Day +3,” Jack McLean wrote in his memoir.

In a fierce battle at Putot-en-Bessin, the Little Black Devils, along with the Royal Regina Rifles and Canadian Scottish Regiment of 7th Brigade of the 3rd Canadian Division, prevented a German breakthrough to the beachhead.

However, three Little Black Devil companies were overwhelmed and came close to being wiped out. Many were captured.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA

Troops from the Royal Winnipeg Rifles and Regina Rifles watch as tanks of the 1st Hussars land near Courseulles-sur-Mer, France, on D-Day in 1944.

“It burns me up to think I spent four years training to get at the other guy and was taken prisoner after less than three days,” wrote Capt. Phil Gower, who was later awarded the Military Cross for his bravery and leadership on D-Day.

“For the longest time,” Jim Bage wrote, “I could not shake the feeling that I was a coward for having been taken prisoner of war.”

The captured were sent to prisoner-of-war camps in Germany. A lucky few escaped.

Some joined the Free French forces, such as Rifleman Tony Hubert.

“To them the only good Boche (a French derisive term for Germans) was a dead Boche. We didn’t take many prisoners,” he wrote. “ I don’t like talking about it. I’m not proud in particular. I’d like to forget it.”

SUPPLIED

Roger Firman c. 1941

Worse was in store for Maj. Frederick Hodge’s company. Fifty-six of his captured men and officers were murdered by Nazis of the 12th SS Panzer Division, also known as “Hitlerjugend.”

D-Day soldier Cpl. Roger Firman, 21, was one of the 56 murdered. Just days earlier, on May 23, he had married his British sweetheart, Jean Cooke, who lived on the Isle of Wight with her widowed mother. In late June, Jean received official notification that her husband was missing.

SUPPLIED

Jean (Cooke) Firman, 1946, Transcona.

While on leave, Firman’s platoon sergeant visited Jean and said he believed Firman may be a prisoner. Nearly a year later, on April 28, 1945, Jean said in a letter to Firman’s mom that she hadn’t given up hope.

“Won’t it be wonderful if our Roger came back,” she wrote. “I still believe he will mum, so don’t give up hoping and praying.”

Jean waited, hoping for the best, until officially notified by the Canadian government of Firman’s death. She was one of approximately 450 women who became war widows of Canadian soldiers.

In 1946, Jean visited his family in Transcona but ultimately chose to return to England to look after her mother. She remarried in 1948 and, in her last letter to Firman’s mother, Jean said she had a baby girl.

According to the Canadian Virtual War Memorial, 96 Little Black Devils were killed on June 8, with a casualty count of 226.

The fight carried on. Between June 9 and July 3, 14 more D-Day riflemen were dead and dozens more wounded. On July 4, the greatly reduced regiment was ordered to capture the airport at the town of Carpiquet on the outskirts of the strategic city of Caen.

SUPPLIED

Rifleman David Gold, of Pine Falls, was among the 56 soldiers slaughtered by the Nazis after capture.

There was no cover and they were soon trapped in a wheat field, fired on by machine guns, heavy artillery and mortars. Non-commissioned officer Ed King, an Indigenous soldier, ordered the troops to “get down and stay the Hell down and keep your head down. You’re no good to us dead! Dig and dig fast!”

But, as the Rifles’ War Diary reflected, many of the soldiers did die before they could dig in.

Lt. Sotheby (Sub) Ketchen’s letter to his father, which was published in the Winnipeg Tribune, detailed the futility of the moment. “We were pinned down to the ground for four or five hours. I really thought the jig was up. It was sure suicide around there.”

The War Diary’s toll was 132 casualties with 56 more Little Black Devils killed. In 30 days without rest, the Rifles had suffered 226 dead, hundreds more wounded and captured.

“There were very few of the RWRs of D-Day left,” Ketchen’s letter continued. “(But) the RWRs have met and licked the best in the German army time and time again during the last few days.”

Out of the 800-plus Rifles who landed on D-Day, only six of the original officers and fewer than a dozen other ranks were with the regiment when they were dismissed by Lt.-Col. Lockhart (Lockie) Fulton in Winnipeg in January 1946.

Remembering

‘The Little Black Devils’

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles Regiment and the Royal Winnipeg Rifles Association commemorate D-Day every year at its memorial at Vimy Park. A wreath is laid, a bugler sounds the Last Post and the most poignant part, according to retired Lt.-Col. John Robins, is when the names of those murdered at Putot-en-Bessin are read aloud by regimental members.

The Royal Winnipeg Rifles Regiment and the Royal Winnipeg Rifles Association commemorate D-Day every year at its memorial at Vimy Park. A wreath is laid, a bugler sounds the Last Post and the most poignant part, according to retired Lt.-Col. John Robins, is when the names of those murdered at Putot-en-Bessin are read aloud by regimental members.

To honour the Canadians who liberated his Normandy homeland, French historian Frederick Jeanne wrote Hold the Oak Line: Illustrated History of the 7th Canadian Brigade.

Along with Jeanne, French screenwriter Antoine Piard wrote a script based on Jeanne’s interviews with Royal Winnipeg Rifles veterans. Their film, The Little Black Devils — From Juno to Putot, which features re-enactors from Normandy’s Maple Leaf Association, will have its première in France on June 6, the 80th anniversary of D-Day.

In an email to Royal Winnipeg Rifles historian Ian Stewart earlier this year, Piard wrote:

‘For Frederick Jeanne and the Maple Leaf Association members, paying tribute to the men of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles is more than important. Unfortunately, the Canadian Army is part of the forgotten troops of the D-Day landings, contrary to the U.S. troops. It’s even more important because they volunteered to liberate us.

Even today, we can’t imagine all those young men leaving their families in Canada to go to Europe to fight.’

When asked how he got through the war without ever being wounded, Lockhart, who was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his leadership and bravery exhibited at D-Day and at Putot-en-Bessin, quipped that luckily all the Germans who had tried to kill him were bad shots.

Over the course of 11 months in action, 3,700 men had served in the Royal Winnipeg Rifles. The regiment suffered 2,339 casualties with 526 dead. It was a staggering rate of attrition. No Canadian regiment suffered more.

In an elegy to his comrades, and, indeed, to all fallen Canadian soldiers, sailors and airmen of the Second World War, D-Day veteran Rupert Fultz, who ended the war as a major, wrote:

When it did come time to die, and some fellows died in Normandy and some in Belgium and some in Holland and some even got to Germany before it was their turn to die.

But it wasn’t like dying amongst strangers, because we had friends by that time — friends from all over Canada whom we knew as well as we knew our own Mothers and Fathers.

Ian Stewart is the author of Voices of War: Royal Winnipeg Rifles Canada 1944-1945 (2020), Royal Winnipeg Rifles Museum.