Most Friday and Saturday evenings in the dark months of winter, the distinctive whir of tire treads can be heard crossing the pavement and ice outside the Centennial Concert Hall, home of the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra.

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra bassist Daniel Perry folds and packs his performance shirt as he prepares to make his way to the Centennial Concert Hall for a performance.

As the downtown Exchange District buzzes with concertgoers shuffling on icy sidewalks and shielding themselves against the bracing Manitoba cold, Daniel Perry, a double bassist, arrives on his custom-built Osto fat bike. He wears only thin merino-wool base layers, snow pants and a light shell. Ice crystals form on the fabric buff he wears over his face to protect his skin.

Perry moved to Winnipeg from Indianapolis, Ind., in 2014. “I had a really shitty Canadian Tire bike I got off Kijiji when I first moved here,” Perry recalls. “I didn’t get very far before I gave up, and I didn’t ride again for a few months.”

Cycling in Winnipeg can be challenging. Winnipeg is traditionally a car city — not to mention the fact it is frequently dubbed the coldest city in Canada and is known for its icy winds. In Winnipeg, about 0.5 per cent of the population commutes by bike. This is on par with cities like Toronto and Ottawa but behind Montreal, where 1.2 per cent of the population cycles.

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

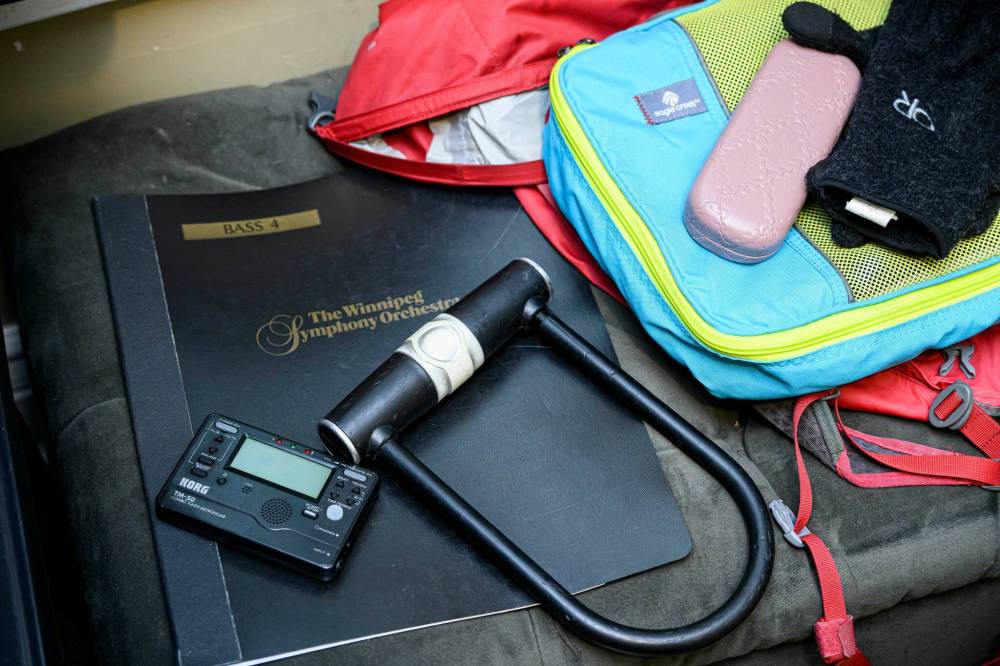

An instrument tuner, a bike lock and a book of sheet music await packing as Perry prepares to ride to work.

Winter cyclists face a myriad of challenges beyond cold toes: unplowed bike lanes make for treacherous riding, road salt corrodes bike chains and snow compacted by car tires makes for an especially slippery commute. Despite these challenges, cyclists in Winnipeg persist, though their numbers dwindle substantially in the winter months.

Chris Baker, the active-transportation co-ordinator for the City of Winnipeg, says the city’s bike network is still in its “teenage years.” It’s come a long way since its infancy, but there’s still a lot of work to do. “Winnipeg has only had a bike policy or a plan since 2015,” he adds. That same year, Perry decided to invest in a decent pair of wheels. For him, cycling in the winter was the antidote to seasonal blues and the anxiety of driving, as well as a way to keep in shape — both mentally and physically.

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

Perry layers up before departing on his ride to the Centennial Concert Hall on a chilly November evening.

In 2014, Perry had been excited to land a spot in the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. It was a prestigious gig: there are only 41 bass spots available across the seven orchestras in Canada that pay above $40,000 per year, and openings are rare. But when he arrived alone on Winnipeg’s distant doorstep, so far from family and friends, Perry felt displaced, anxious and adrift.

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

Perry turns on his bike’s tail light prior to starting his ride.

I know how Daniel felt. I, too, moved from the U.S. to join the WSO. When I arrived 15 years ago, I too struggled to adjust to Winnipeg being my new home.

Being part of the city’s professional symphony orchestra, as Perry puts it, felt like being in a “bubble that’s disconnected from the community.” With erratic work schedules and intense daily practice, newcomers to the symphony often settle into an insular, indoor existence, entrenched in the social circle and culture of the orchestra. In Perry’s small friend group, that culture involved many evenings each week of socializing and heavy drinking, not uncommon among symphony musicians.

After a year stuck indoors, suffering from asthma and allergies caused by dust and pet dander in friends’ homes, Perry committed to changing his habits. He vowed to stop drinking for a few months, start getting outdoors and begin exercising. Perry traded in his used Canadian Tire bicycle for a new road bike, better suited to longer rides and city streets.

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

Perry plans the route he’ll take for his evening ride.

He began pulling up the Google Maps bike feature and exploring Winnipeg. Suddenly, he found himself seeing things he’d never noticed while driving.

Before long, he was hooked on biking. Within a couple of years, he’d given up his car altogether and relied on his bike as his primary mode of transportation, including riding to work. As a fellow orchestra member, I always felt I could be forgiven for driving to work. My cello — my most precious possession — is, like all stringed instruments, susceptible to extreme cold and heat. It’s also next to impossible to transport by bicycle.

Perry faces an even bigger barrier to commuting by cycle in a wintry, windy city — he plays the double bass, one of the largest instruments in the orchestra, alongside the harp and piano. Basses are cumbersome and heavy, nearly two metres tall and extremely delicate. Like all string instruments, they are pricey and can cost as much as buying a car. Perry’s solution: use his second bass to practise at home and avoid transporting his primary bass to and from the concert hall.

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

Perry cycles eastbound on Assiniboine Avenue past the Manitoba Legislative Building. Winnipeg is traditionally a car city in which only about 0.5 per cent of the population commutes by bike.

Perry’s relationship with Winnipeg has evolved in tandem with its biking infrastructure. There are now more than 400 kilometres of bike lanes, greenways and multi-use paths. “(I discovered) how (routes) are connected to the riverside paths, they go through neighbourhoods and next to green spaces, and (I) actually got to see that side of the city,” Perry says, speaking both scenically and geographically. “I was like, ‘Oh — this is a beautiful place!’”

These days, Perry is a local fixture along Winnipeg’s bike lanes.

He has also become deeply entrenched in the city’s cycling community. As local cyclist Leslie Parisien puts it, “You can’t throw a rock around here without finding someone that knows Daniel.”

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

Perry rode to a fourth-place finish in Alaska’s fabled Iditarod Trail Invitational — a behemoth fat-bike ultra-marathon that takes place every February, covering more than 560 km.

He volunteers with organizations like The Wrench, which uses reclaimed parts to refurbish bikes and offers classes, workshops and community programming with the stated aims of “educating youth, empowering volunteers and providing people with affordable, sustainable active-transportation options.”

Perry’s infectious enthusiasm for biking has rubbed off on his colleagues at the WSO.

“I do try to celebrate that since I started, we’ll have winter days where there are between five and 10 people riding to work in the middle of winter,” Perry says. “For me, that’s where I have power … even if that’s in the smallest of ways, it’s a change, and that’s what I can do.”

The municipal government also appears to be taking notice of the growing cycling community: Baker notes the City of Winnipeg has committed to increasing its active-transportation budget. (The 2025 city capital budget for the pedestrian and cycling program is $2.2 million, and is forecast to rise to $5.4 million in 2026). Still, some cyclists feel current efforts aren’t enough.

According to Manitoba Public Insurance, every year an average of four cyclists in Winnipeg are killed in collisions with cars, with an additional 78 injured. Edmonton, by comparison, has an annual budget of $33.3 million for cycling infrastructure and plans to expand its bike network through 2026. On average, there was only one cyclist fatality per year there from 2012-22.

Few studies have been done on the impact of infrastructure design on cyclists’ safety. Those that have been done have indicated that when dedicated, bike-only infrastructure exists, the risk of crashes and injuries is significantly reduced, in addition to providing sustainable transportation options and benefits to public health.

“I do try to celebrate that since I started, we’ll have winter days where there are between five and 10 people riding to work in the middle of winter … For me, that’s where I have power … even if that’s in the smallest of ways, it’s a change, and that’s what I can do.”–Daniel Perry

Perry and others believe well-maintained, dedicated bike lanes are essential to prevent fatalities like one in June when longtime cyclist Rob Jenner was killed on Wellington Crescent while riding to work. Patty Wiens is one of those working to ensure city officials make cycling safe.

“We have to hold them to task,” Wiens, known as the “Bike Mayor of Winnipeg,” says. (Bike Mayor is a title bestowed on 141 people in dozens of countries by the Bicycle Citizen Network, an Amsterdam-based organization providing support to community-led cycling initiatives and Bike Mayors across the globe).

When Weins meets with Mayor Scott Gillingham — she calls him the “Car Mayor” — she pushes for three changes to make roads safer for cyclists: reduce residential speed limits to 30 km/h, eliminate right turns for cars at red lights and remove all slip lanes.

Weins, who rides an e-bike, finds her sense of community enriched by cycling activism: “We’re too isolated. I think that is why the bike community has become so crucial. We find these people who feel the way we do. We bond together, and then we’re outside together. I’ve added probably 200 new friends to my life that I can honestly say are friends.”

While Winnipeg’s punishing winters and fragmented bike routes scare off many cyclists, Perry remains undeterred. And his relationship to the WSO has changed for the better as well. With a deeper connection to the community, he says, “now for me, this is more of a job than an identity.”

Finding a healthier work-life balance has allowed Perry to explore the world of competitive winter marathon bike races. As he gradually increased his distance, he started to eye the 268-kilometre Toscobia Winter Ultra in Wisconsin. “It sounded kind of ridiculous, but also attainable enough that I wanted to go for it.” He thought, “If this is an actual event, and people do this all the time, why can’t I be one of those people?”

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

Perry arrives at the back stairs of the Centennial Concert Hall.

Now, Perry is not only one of those people, but he is incredibly successful. He finished first in the 2023 Tuscobia Ultra, in which he also won a spot to compete in Alaska’s fabled Iditarod Trail Invitational — a behemoth fat-bike ultra-marathon that takes place every February, covering more than 560 km. Perry, one of only a few rookies on the trail this year, rode to a fourth-place finish.

Though Perry and I have sat in close quarters on the orchestra stage for 10 years, I visited his home for only the second time about a month after that race. I found him sitting cross-legged on his sleek grey sofa, sipping a cup of black coffee. Bella, a small, elderly rescue he was dog-sitting, was curled up like a croissant at the opposite end of the couch. Sporting a mullet and trimmed beard, he was “still processing” the Iditarod experience and seemed philosophical.

“I’m not just obsessed with bikes,” he says. “I use it as a tool or an avenue for other things.”

Perry spends a lot of time on his bike in reflection, he says, doing what he calls his “inner work.” And without his bike, Perry knows his connection to his community in Winnipeg wouldn’t be as rich.

Beyond the physical benefits of cycling year-round, biking has also propelled Perry’s personal development and community activism. Cycling is no longer simply a mode of transportation.

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

After parking his bike in the storage closet, Perry tunes his bass minutes prior to hitting the stage at the Centennial Concert Hall for a performance Saturday evening.

There are many sub-zero evenings when Perry arrives at the concert hall, rosy-cheeked and refreshed from his commute. He’s already started mentally and physically preparing for his performance on his ride to work.

“I like to take time to think about my breathing and my posture and my muscle engagement while I’m riding… this helps me warm up and think about using my entire body to play bass,” he says.

He wheels his bike backstage, past colleagues already in their evening dress. Perry and the other bassists he inspired to ride to work leave their bikes in a large instrument-storage room. Fat bikes parked between instrument cases and storage lockers spark conversations about recent rides, road conditions and weather. Layers of sweaty clothing are peeled off and hung on handlebars to dry, as orchestra members change into tuxedos, dresses and other formal wear.

As the ice melts and drips from his bike tires, Perry sits on stage, just one cog in the wheel of the orchestra, anticipating his ride home after the concert amid the snow falling gently outside. Perry is thankful for the relationship he has cultivated with cycling. “I needed something that I did on my own terms, that I could have as a passion away from music,” he says. “My world is so much bigger now.”

MIKE SUDOMA / FREE PRESS

Perry warms up on stage with his fellow musicians while concert-goers file in.

Emma Quackenbush is a writer and cellist who has performed with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra for 15 years.