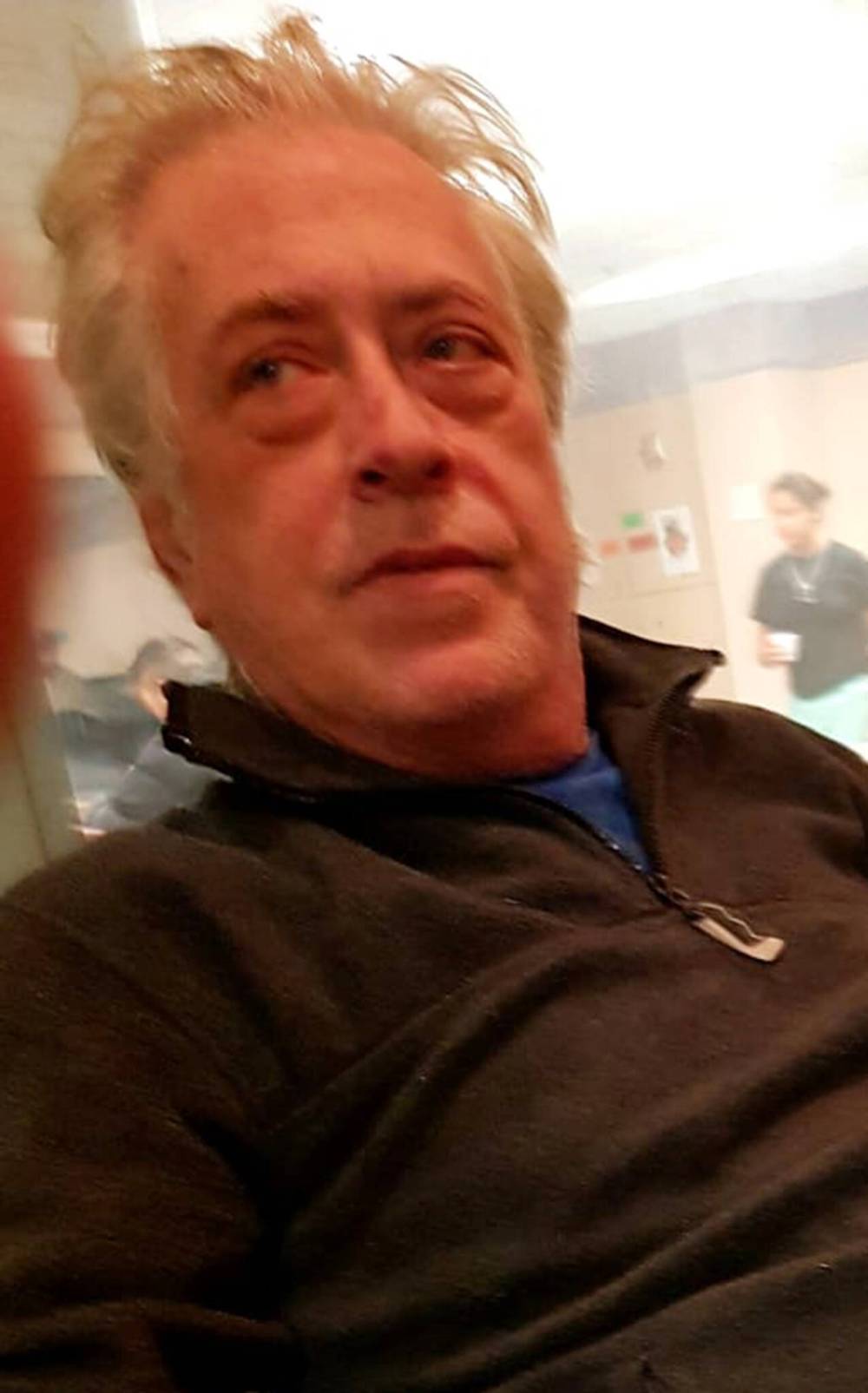

About two weeks before 59-year-old Bradley Singer was shot and killed by Winnipeg police in mid-February, heavily armed officers had surrounded his North End home while he was inside in the grip of a mental health crisis.

Bradley Singer was shot and killed by Winnipeg police in mid-February. (Supplied)

Gerry Singer, his brother, said Friday the situation was confusing and distressing for Bradley, who was sought under a Mental Health Act order.

On Friday, the family shared video of the first encounter, on or about Jan. 27, which had been taken by a neighbour. Multiple officers and several police vehicles can be seen in the video, along with a drone, and officers are seen breaking a window.

“This vulnerable, mentally ill man must have been extremely frightened when confronted by a group of heavily armed police officers in what is commonly known as SWAT team gear. Who knows what role that experience with the police tactical team played in his mind on February 13, 2024, when he was shot dead by the police,” said Martin Glazer, lawyer for the Singer family, at a news conference.

After being taken into custody, Bradley was hospitalized.

On Feb. 13, about a week after he was allowed to return home, investigators with the provincial Independent Investigation Unit went to Singer’s residence and informed him Bradley had been shot multiple times by police during a mental health call to his home at 259 Magnus Ave.

Later, he was told his brother had died in hospital.

“After that statement, my life has changed forever,” Singer said Friday. “I don’t think I will ever get over my brother’s needless death or recover from it.”

At the news conference, Singer was joined by the family members of Afolabi Opaso, a 19-year-old University of Manitoba student who was shot and killed by police at an apartment on University Crescent on Dec. 31, 2023. His friends have said he was having a mental health crisis at the time

Both families demanded a joint inquest into the men’s deaths and asked that it be fast-tracked.

In Manitoba, an inquest must be held when the chief medical examiner believes a death was caused by use of force from a police officer.

Legal representation for both Singer and the Opasos say they want urgent action.

“I asked the chief medical examiner to provide… my office with a copy of the medical examiner’s report and the autopsy report as soon as possible, by law we’re entitled to both of those. So far, nothing,” Glazer said.

“You would think by now they would at least have the medical examiner’s report, the autopsy was done. Where’s the autopsy report? We’re not getting answers. We’re not getting anything.”

A spokesperson from the chief medical examiner’s office said there is no timeline for when the mandatory inquest would begin.

Joint inquests have occurred. In November, an inquest began probing the cases of five men who died following altercations with Winnipeg police.

Counsel for the Singer and Opaso families said Friday the similarities between both incidents could shed light on how police procedure can be improved to prevent such tragedies.

“Are (Winnipeg police) equipped as a police force to even be in the forefront answering these kind of calls?” said Jene-Rene Dominique Kwilu, a lawyer for Opaso’s family. “That’s why I think a joint (inquest) and the similarities will help to shed light, in terms of the practices in place.”

Afolabi Stephen Opaso, 19, was having a mental health crisis when Winnipeg police officers were called to an apartment suite at about 2:30 p.m. on New Year’s Eve. (Supplied)

Winnipeg police said Afolabi, an international student from Nigeria, was armed with two knives when officers responded to a mental health call.

Singer, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia, was carrying a crowbar and had discharged a fire extinguisher at police who had been sent to apprehend him for a non-voluntary medical exam. He was shot after confronting officers with a “large, edged weapon,” police said.

“I can’t imagine how my brother felt dying like that. I mean, it’s got to be horrific. (The police) mentioned three bullets, but, (based on) what’s left in our house, I think it was upwards of 10 bullets,” Singer said.

Both families have incurred significant costs. Singer said his brother’s burial cost about $18,000, and the house needs $15,000 in repairs from damage caused by police entering forcefully. The Opaso family had to pay to fly to Canada for the burial.

“They wished at least the government would extend some sort of cheque to help them bury their brother who was killed by the police, but nothing,” said Benjamin Nkana Bassi, who is also a lawyer for the Opaso family.

Glazer, Kwilu and Bassi are working pro bono.

When asked if the province would extend support services to families of people killed by police, Justice Minister Matt Wiebe pointed to the 2024 budget, which includes funding for additional mental health staff to work alongside law enforcement.

“We are also in the process of reviewing policing standards across Manitoba and want to ensure that incidents like these ones never happen again,” he said in an email.

Both legal teams say the Alternative Response to Citizens in Crisis, the program in which mental health workers accompany police to well-being calls, is flawed as long as police are in charge.

“We think that it’s not for the police to determine if it’s appropriate for ARCC to be deployed,” Kwilu said.

malak.abas@freepress.mb.ca