It’s chilly and after dark in one of the city’s reputedly most dangerous areas and kids are playing a game of pickup soccer. Relatives and friends mingle at the field’s edges, chatting and stopping balls whizzing towards the streets before anyone chases them into traffic.

Before the snow falls, it’s a scene that will play out almost daily in Winnipeg’s Central Park.

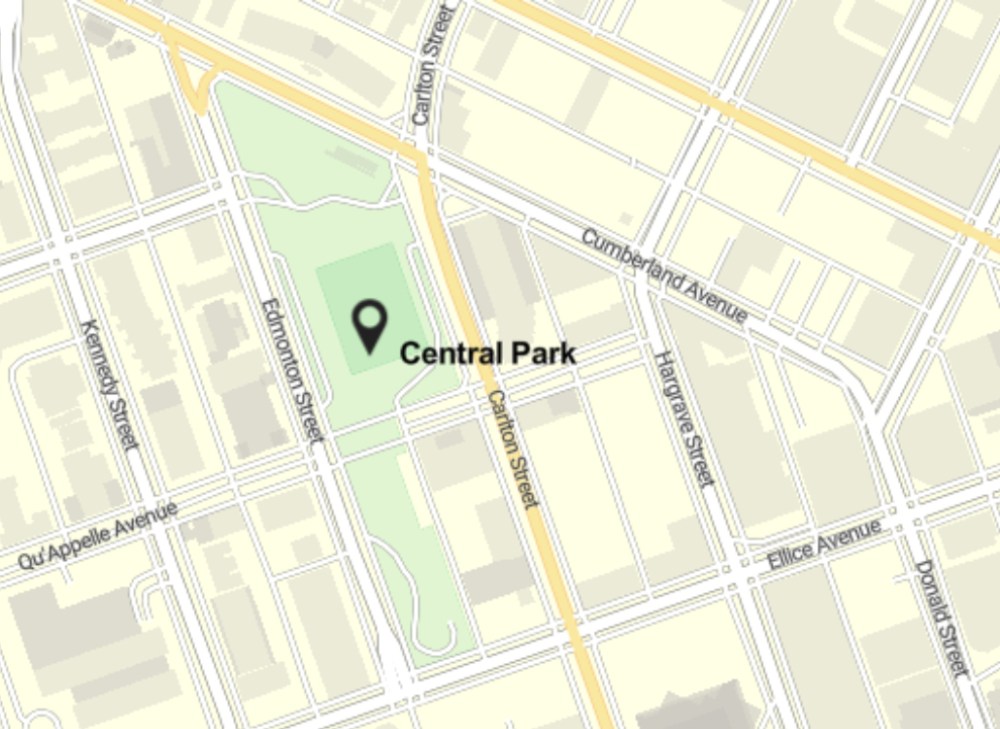

Tucked behind Portage Place — bordered by towering apartments, community outreach organizations and a 110-year-old church — the park is the social focal point in a dense neighbourhood that’s largely a port-of-entry for newcomers. A great many of them are refugees.

Among the spectators is Genet, taking a break from volunteering with Food 4 All, a multi-agency initiative that gives out free food to area residents.

She doesn’t give her last name: “Trust me, everyone knows (me)!” Genet immigrated from Ethiopia in 2006 and lives, still very happily she says, next to the park. It was once unkempt, forest-like, and a site of gang activity when she first arrived.

Now? She looks towards the soccer field and gestures.

Central Park is a social focal point in a neighbourhood that serves as a port-of-entry for newcomers.

“This helped… Youth come to play soccer, while adults sit around, exchange ideas, get information,” Genet says.

“Like, I’ll come here, and say, like, ‘Oh, did you know I never got my PR (permanent resident) card? Yeah, I never got it. I’ve been here for a year now, so where to go, what to do?’”

Because her English was strong when she arrived, Genet jumped into professional courses right away. Eventually, she assisted as a trainer in newcomer classes. She says many refugees are more reticent than her: “They come through a lot of trauma so they don’t think they have a voice.”

Newcomers in the area navigate an alphabet soup of government, housing and other social service bodies. A bridge — and sometimes refuge — is the bustling social life unfolding in the park, inside and outside Knox United Church, and at the Islamic centre that faces the greenspace.

“That’s how our communities developed, by talking to each other, by finding information from each other and showing us the way,” she says.

Genet’s insights relate in interesting ways to the idealized image of central parks.

“That’s how our communities developed, by talking to each other, by finding information from each other and showing us the way.”–Genet

Owing partially to the prestige of New York’s Central Park (designed, according to its website, as “a beautiful and democratic space for all”), this image is akin to the Greek agora: a lively, open space for people to trade ideas and goods, play and raise their voices, and weave the fabric of a healthy civic life.

It encourages a view of central parks as both a vital microcosm and vehicle for civic democracy.

This all sounds nice, but there’s one problem: who but the well-heeled can most comfortably root themselves in the upscale neighbourhoods that usually border the lushest of public parks, such as Stanley Park in Vancouver or High Park in Toronto? These parks may belong to the public but by fate of proximity and wealth, not everyone enjoys the same access.

Winnipeg’s Central Park, born at the turn of 20th century, is following a different path. The rectangular space is an island within an archipelago of public housing complexes.

These apartments help make up the downtown neighbourhood — also known as Central Park — which reportedly has a crime rate about 50 per cent higher than the rest of the city. The area is a triangle inside the intersections of Colony, Cumberland and Ellice. The park is in the middle of it all.

The park, small and humbly beautiful, is a gathering place for those perceived by many to be marginalized in the broader public arena, the big agora. As a space for self-determination something complex has clearly been happening here.

Central Park consistently has one of the lowest voter turnouts in the city. This fits within a well-established trend correlated with low-income neighbourhoods.

Central Park is also one of Winnipeg’s most diverse neighourhoods — according to the 2021 census, about 15 per cent Filipino, 17 per cent of Indigenous ancestry, 18 per cent of Indigenous identity, and 38 per cent Black; blocs segmented further by internal linguistic and cultural differences, especially dizzying in the case of African newcomers.

Such diversity reminds us that Central Park is hardly univocal, a community as eclectic in viewpoints as peoples; something one tries to bear in mind while speaking to its residents.

And it’s hard not to wonder if the English language barriers to which this diversity points also have something to do with low voter turnout.

Yet democracy takes many forms, some subtle, even sneaky. And weak voter turnout doesn’t mean there aren’t spirited grassroots efforts in Central Park to steer the big decisions critically affecting the neighbourhood and its residents.

Central park is a gathering place for many.

Take the park itself. Its current incarnation is the fruit of a $5.6-million revitalization project, bankrolled by all three levels of government, that began in 2008. Today it’s hard to imagine it without its hockey, volleyball, and especially soccer games, but the idea for the pitch was almost punted aside.

The CentreVenture Development Corporation, an arm’s length agency of the municipal government, put Central Park advocates in charge of the project’s consultation process.

They found the community seemed unanimous in wanting one thing: a soccer pitch. Reportedly, the landscape architects first pushed back, citing cost and practicality.

So, residents brainstormed and proposed the artificial turf field serve as a hockey rink in the winter, a soccer pitch in the summer. This settled the matter and construction began. By 2012, workers had left the upgraded park and people had flooded its new pavilion, waterpark and soccer pitch.

“It’s nice to see a plan that conforms with the people’s wishes,” said Bill Millar, former reverand of Knox United, during the construction. The planners “engaged the community… were able to incorporate their not-so-simple needs in a vibrant development.”

Luxton Komaransky (then 1) takes a drink from a water feature at the splash pad in Central Park in June 2023.

But then there’s the failed experiments in participatory design. Take Centre Village, a few minutes’ walk from the park. The visually elegant 25-unit complex, designed by 5468796 Architecture and Cohlmeyer Architecture Limited, opened in 2010 amid much fanfare.

But it was criticized by some residents for being unlivable and reportedly descended into a haven for crime.

After multiple fires, the tragic, long-vacant Centre Village faced the wrecking ball in September, a mere 14 years since it opened.

Fingers point in every direction. Colin Neufeld, a partner at 5468796 Architecture, defended the design in 2016, saying the “focus group saw the project every step of the way.”

Ross McGowan — the former head of CentreVenture, which developed the project with Manitoba Housing — says the initiative was inherently flawed, even inattentive to community needs. “Maybe that’s part of the issue… (we thought) ‘Well, it’s just affordable housing, let’s not get too wound up about it.’”

What’s certain is that this wasn’t the neighbourhood’s finest hour in participatory decision-making.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

Volunteers Elaine Dukuly (left) and Raymond Ngarboui distribute free food for Food 4 All adjacent to Central Park, where fellowship and vital information are also shared freely.

Back to Central Park: not far from Genet, works Raymond Ngarboui, an organizer at Food 4 All. As well as having helped co-ordinate grassroots input into projects like Centre Village and Central Park’s upgrade, Ngarboui is a project co-ordinator at Community Education Development Association and has a long CV relating to the park.

The 2022 Queen Elizabeth II Jubilee Medal recipient, who came to Canada by way of Cameroon as a refugee in 2005, is shuffling big boxes of food and chatting chipperly in French and English.

He introduces me to Mariama Mahamadou, a Central Park resident for the past few years. My questions start awkwardly, in a heavy-handed way. “Do you feel heard by local government and decision-makers?” I ask in broken French. Mahamadou smiles and smoothly changes the subject.

We talk about the market, where she’s a vendor, that pops up weekly in the summer. She describes the ginger and roselle juices she preps, and the flow of crowds between market and park, where her children play. “(The park) is good for the kids, they play soccer, they go wash themselves when it’s hot,” she says.

Mahamadou is talking about the park’s wading pool, fitted with water fountains and cannons that become a stage for children’s play and parents’ mingling in summer, with neighbourhood audiences in the overlooking apartments.

Children playing, like Amani (left) and Aisha Jama, is also anchoring adults to Central Park.

Urbanist Jane Jacobs’ school of thought has it that highrises, by taking eyes off the street, leave crime to creep below. But I wonder if the park’s “insularity” — a circular arena of sorts, always watching itself even from a height — helps ease that risk.

So, what’s next for the Central Park area, and what role will the residents play in shaping its future?

Back in 2012, Ngarboui was involved in the new park’s ribbon-cutting events and already voicing concerns improvements might stop there. “It’s meaningless to have people with nice infrastructure but with empty stomachs,” he pointedly told the Free Press at the time.

Today, he doesn’t hesitate to say he doesn’t feel the big decision-makers are listening or doing much for the neighbourhood anymore.

“The residents’ voices are not sufficiently heard as they are not consulted (by city planners),” he says, and highlights the lack of “initiative(s) that aims at enhancing the housing, economic and sociocultural development of the Central Park area.”

“The residents’ voices are not sufficiently heard as they are not consulted (by city planners).”–Raymond Ngarboui

For their skeptics, community consultations can be rubber-stamping exercises or side shows that give a megaphone to know-nothings. For their boosters, they’re vital, if imperfect, avenues for community self-determination.

Ngarboui highlights a lack of recent development and consultation in the neighbourhood. But there are big things in the works just beyond Central Park, on Portage Avenue where residents flow; projects trumpeting “public consultation” but with contrasting connections to local communities.

One is at the Hudson’s Bay Company, the other, catty-corner, at Portage Place. The first project, under the name Wehwehneh Bahgahkinahgohn, will see the shuttered retail outlet of the former fur trading company transformed into an Indigenous-led affordable housing, cultural, and service hub.

The other will see a struggling mall — known for its tense relations with downtown residents — overhauled, under new ownership, to erect health-care and housing towers. Among the other planned additions to the $650-million redevelopment is a grocery store, sorely needed downtown, and a health facility.

So far, the Southern Chiefs’ Organization and True North Real Estate Development, these buildings’ new respective owners, project an air of alignment, and they are co-operating on certain initiatives.

“Together,” says TNRED president Jim Ludlow, “we will bring forward thinking solutions to our collective pursuit of market and affordable housing, health care, Indigenous relations and reconciliation, and downtown revitalization.”

“Together, we will bring forward thinking solutions to our collective pursuit of market and affordable housing, health care, Indigenous relations and reconciliation, and downtown revitalization.”–TNRED president Jim Ludlow

In this spirit, TNRED say they’ve mounted two consultations, involving “a working group of several dozen stakeholders,” hundreds of surveys, and pop-up events at the mall drawing hundreds of participants. They also say that this process’ resulting reports “prioritized” some of the new Portage Place’s planned features, like the grocery store and health facility.

“I’ll be happy if I see it,” says Elena, an Indigenous woman who takes her daughter to play in Central Park, about the mall’s new social priorities. “There’s a lot of broken promises to Native people.”

All this scrutiny over community consultation, and I can’t help but face how basically bumbling my own efforts in this area are.

Before meeting Genet and Raymond, I trace the park’s edges, as I have before. I’m anxious to talk to those with no institutional affiliation, anxious I won’t talk to enough people across demographics, anxious that in talking my voice will carry too loudly.

Today, I make conversation mostly with Eritreans and Ethiopians. I hear frustrations that, language barriers aside, are clearly about labyrinthian public institutions and unpleasant housing. But sooner or later things come back to the park.

“I love the place,” says Rediet, who no longer lives nearby but came directly from his construction shift to see old friends.

“It’s beautiful,” says Mohamed, a local resident, in a separate conversation. He later shows me a photo of his soccer team. “We are mixed, we are from any country.”

In a particularly un-fun mood, Noam Chomsky, the linguist of Universal Grammar, once said: “sports, that’s another crucial example of the indoctrination system”; a deliberate distraction apparently from organizing, activism, education. The sentiment seems out of touch and I’m pretty sure he didn’t have something like Central Park’s soccer life in mind.

No one’s making the mistake of thinking the park’s recreations are the perfect melting pot.

Still: who can’t admire the way they bring together the neighbourhood’s residents, separated by who knows how many cultures and languages? Universal Grammar, indeed.

“Youth come to play soccer, while adults sit around, exchange ideas, get information,” to repeat Genet’s remark. “That’s how our communities develop.”

Idealistic talk of the Greek agora may be too caught up in an old sort of democracy that told the non-propertied to shove off. But isn’t it realistic to see in the picture Genet paints the workings of self-determination?

conrad.sweatman@freepress.mb.ca