Murray Sinclair, the groundbreaking Indigenous lawyer who led inquiries that exposed racial injustice and redefined how Canadians see Indian residential schools, has died. He was 73.

Sinclair, whose spirit name is Mizhana Gheezhik (The One Who Speaks of Pictures in the Sky), died early Monday morning at St. Boniface Hospital surrounded by family.

A sacred fire will be lit in his honour on the grounds of the Manitoba legislature, ironically on the spot where the Queen Victoria statue once stood.

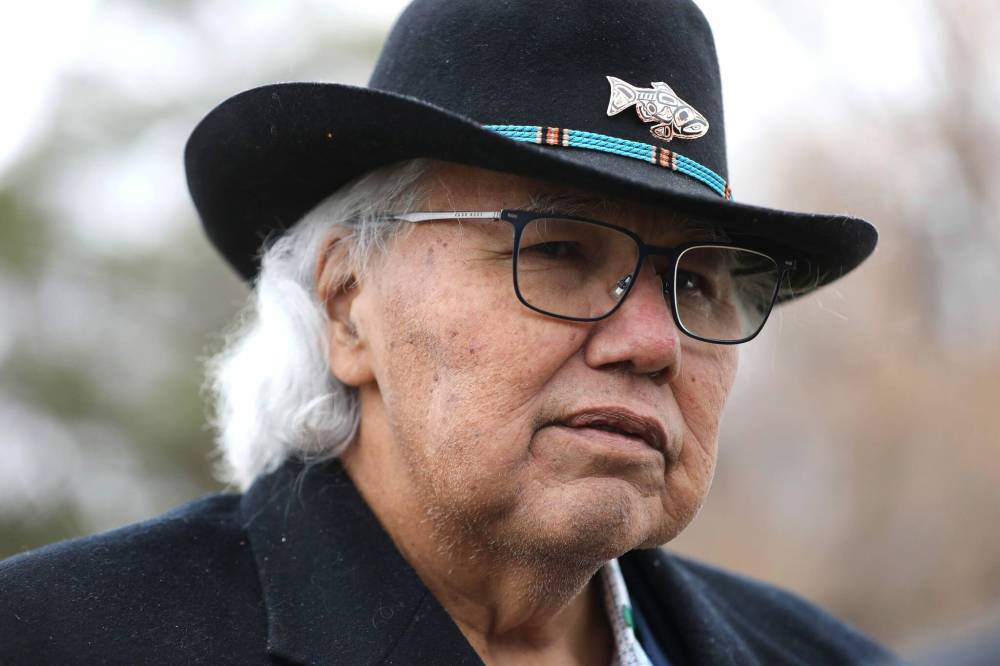

The Hon. Murray Sinclair, Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, in 2022. (Ruth Bonneville / Free Press files)

Sinclair’s long and distinguished career of public service extended from the legal system to politics as he also served as one of Manitoba’s senators from 2016-2021.

Raised on the former St. Peter’s Indian Reserve near Selkirk, Sinclair earned accolades early as he was his high school’s class valedictorian and athlete of the year in 1968.

He graduated from the University of Manitoba’s law school in 1979, setting him on a course to become the province’s first Indigenous judge and only the second named to the bench in Canada.

In 1988, Sinclair rose to prominence when he was appointed co-commissioner of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry. The three-year inquiry, triggered by the police shooting of Indigenous leader J.J. Harper and the murder of Helen Betty Osborne, a Cree teen in The Pas, laid bare the systemic racism that still plagues the criminal justice system.

Sinclair and co-commissioner Judge Alvin Hamilton made nearly 300 recommendations. In 2013, on the 25th anniversary of the start of the inquiry, Sinclair said some progress had been made but expressed concern he wouldn’t see tangible movement on some of the more sweeping recommendations, such as the creation of a separate aboriginal justice system, in his lifetime.

“The same factors that spoke to over-incarceration in 1991 when we did our analysis — the systemic discrimination, the lack of employment, the lack of social programs that address crime and misbehaviour, the poor educational attainment, higher suicide rates — are still present,” he said at the time. “But I think we’re also now beginning to see and understand the intergenerational implications of residential schools.”

In 1994, Sinclair led the Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Inquest that reviewed the deaths of 12 children at the Health Sciences Centre.

He often said the inquest, which spanned five years, exacted a profound emotional toll and was one of the reasons why he initially refused to lead the country’s reconciliation process.

“Hardly a week goes by that I don’t think about those kids,” Sinclair told the Free Press on the 20th anniversary of the inquest.

In 2009, however, Sinclair moved to the national stage as he began a six-year journey as chair of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. That cross-country odyssey exploring the devastating impact of the residential school system resulted in 94 calls to action, which are helping reshape Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples.

“My view and my comment is that being in charge of the TRC and being involved in all of those hearings, and listening to all those survivors, profoundly changed my way of thinking about the government, thinking about Canadian society, and thinking about how far we have to go in order to restore Indigenous peoples’ self-respect,” Sinclair wrote in his autobiography published shortly before his death. “Because we will never achieve reconciliation without self-respect. Reconciliation is about mutual respect.”

The honours and accolades for Sinclair speak to the depth and breadth of his service to the province and country. He is a companion of the Order of Canada and a member of the Order of Manitoba. He lists scores of honorary degrees and a bronze bust of him stands in Assiniboine Park as part of the Citizens Hall of Fame.

“The city has to see itself as a city that includes Indigenous people in prominent ways, not just as a problem in part of the city,” Sinclair said in 2022 when he became the first Indigenous member of the roll of luminaries.