When it came to a love of live concerts and the music of Bob Dylan, you could say Alan Small was like a rolling stone.

Or as Small himself might have said: wie ein rollender stein.

That’s because Small, who died of cardiac arrest at 56 on May 3 in Vancouver as he was returning from vacation, was not only a fan of Dylan and his music — heck, with more than 40 live shows under his belt, you could say he was a fanatic about the singer — he was also fluent in German.

While that was part of Small’s personal life, it was what he did publicly that touched many people in the community.

Small was a reporter and editor with the Free Press for 26 years. During those years, he wrote stories, covered concerts, edited copy, designed pages and even crafted editorials on the issues of the day.

And for several of those years, his colleague Jill Wilson sat at the desk right behind him.

That turned out to be a blessing for Small.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS files

In the Free Press newsroom with colleague Jill Wilson

Small started developing problems with his kidneys in 2006. For a time, dietary changes were all that was prescribed — he had to give up his favourite fast food, KFC — but dialysis eventually became necessary. He spent many hours of each week connected to his home dialysis machine. He was told by doctors it would likely be years before he received a kidney transplant.

Sitting so close to Small, Wilson said she overheard and followed his medical story for the better part of a dozen years. She realized she had two healthy kidneys and could donate one to her longtime colleague.

“It would be an understatement to say I was stunned — I couldn’t speak,” Small wrote, after receiving a kidney, of his reaction to Wilson’s offer.

“A kidney? From Jill? For me? What could I have done to deserve this kindness? It was overwhelming.”

The kidney Small received five years ago wasn’t from Wilson directly; her organ would have been rejected. But she found she could still help as a living donor in the kidney paired donation program. She and Small were added to a database with other incompatible donor pairs across Canada to find matches among them. She eventually donated to stranger in another city, while Small received a kidney from another stranger in the chain of donors and recipients.

“They said it would be three to four years before a chain would be made, but they called me a few days later,” Wilson recalled recently. “It was just something I could do to help.

“I like to think he had a better life the last few years because of this.”

Small’s brother, Dan, said the kidney illness “came from out of the blue.”

“He told me one day he was working on the computer and it looked blurry,” Dan said. “So he went to see an eye doctor, who sees nothing, but had his 100-year-old blood pressure (machine) and put it on his arm. It was on the top end, so he went to the ICU, where it took three or four days to reduce his blood pressure. By then, his eyes were back, but they found out his kidneys were the problem.”

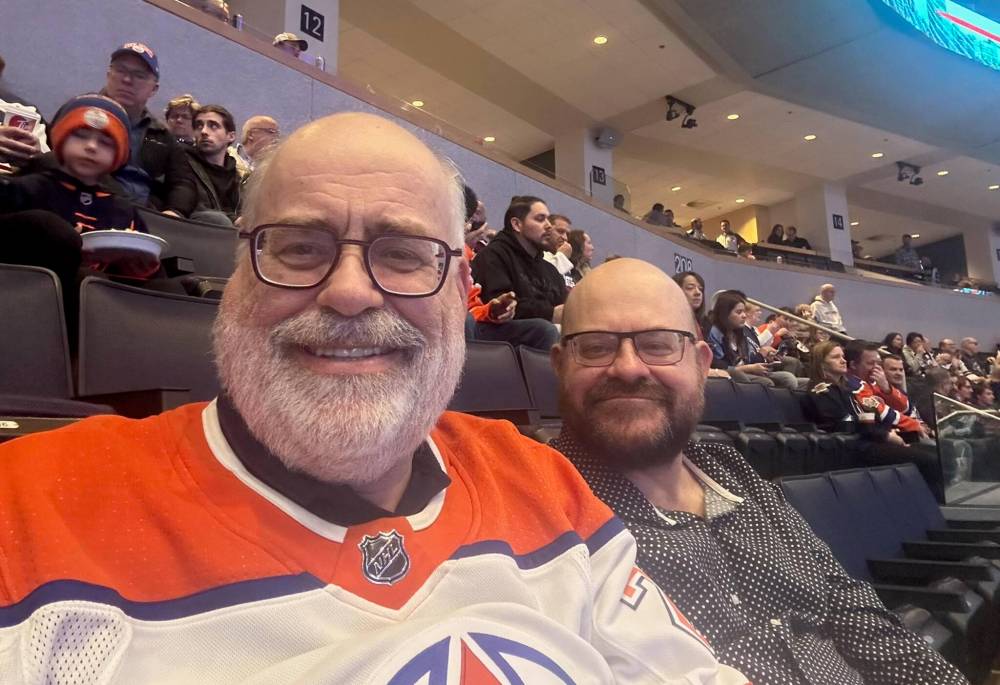

SUPPLIED

Small and his brother Dan at a recent hockey game.

Dan said when his brother went on dialysis “it was a pretty tough time for him.” He said Small may have only lived another five years with the donor kidney, but they were five years he wasn’t attached to a dialysis machine.

“He was very, very fortunate.”

“It is tragic what happened to him, but he had five great years in between. He was healthy.”

Small was raised with two older brothers on a mixed grain and livestock farm near Radway, Alta., population 231, about an hour northeast of Edmonton.

While he didn’t grow up to be a farmer, his dad did steer him to get an agriculture economics degree at the University of Alberta.

Small’s brother recalls seeing signs of a possible media career in his future — he would do play-by-play commentary for made-up curling games at home — but it was at university when the journalism bug fully bit him.

In Small’s off-time, he began volunteering at the university’s student newspaper, The Gateway. He rose to be the paper’s sports editor for two years, before joining Alberta Report as a researcher.

From there, Small worked as a reporter for three years at the Morinville and District Gazette, and then the Medicine Hat News, before moving to Winnipeg to join the Winnipeg Sun as its assistant news editor in 1997.

A year later, Small joined the Free Press as a copy editor and never left. He was most recently in the arts and life section, where one of his final assignments was a four-star review — likely written on his reliable iPad — of country superstar Luke Bryan’s appearance at Canada Life Centre. Small covered Winnipeg’s arts and music scene with care, offering equal spotlight to international touring acts and local up-and-comers.

With his team (back row, from left: Ben Wiebe, David Sanderson, Trevor Malo, Alan Small; front row, from left: Sandra Kehoe, Kyla Wiebe, Jill Wilson and Chris Carman), the trivia buff often won the Alzheimer’s Society of Manitoba’s annual trivia fundraiser.

In his off-time, Small — who never encountered a situation that couldn’t be summed up with a pithy quote from his beloved SCTV — golfed, curled, played in a trivia league and was heavily involved in Fantasy Baseball. He even enrolled at the University of Manitoba part-time and received a bachelor of arts, majoring in German studies.

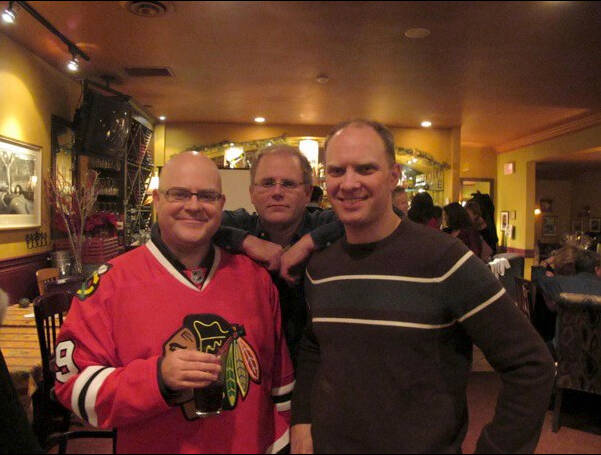

Jill Wilson photo

Small (left, with Free Press colleagues Mike Sawatzy and David Fuller) was the lucky winner of a hockey jersey at the paper’s 2010 Christmas party.

And he went to concerts.

Colleague Mike Sawatzky joined Small at many of them — often in the spur of the moment.

“One minute you were casually discussing the possibility of a Dylan show somewhere and a few hours later, Al had booked tickets and sussed out travel plans,” Sawatzky said.

“You could wonder about a 13-hour drive to Rockford, Illinois, after a Friday-night work shift to see Bob play the next night and his response would be immediate: ‘We should do that.’”

Sawatzky said the more unusual destination and venue, the better.

“It could be an amphitheatre in Cincinnati or Milwaukee, a casino parking lot in Elizabeth, Indiana, a baseball stadium in Fargo, a hockey rink in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, or a basketball gym in Cedar Falls, Iowa — preceded by a quick detour to pay respects to Buddy Holly, Richie Valens, and J.P. (The Big Bopper) Richardson in a cornfield north of Clear Lake.”

Other musical favourites Small would travel to see included Bruce Springsteen, Tom Waits, Steve Earle, the Allman Brothers Band and the Tedeschi-Trucks Band.

Sawatzky said Small had seen and heard Dylan so many times he could recognize lyric changes done on the fly, but he didn’t think he was anywhere near Dylan’s biggest fan.

“Al admitted he was an ‘amateur’ in the world of Bob, whose dedicated following includes many fans who have seen hundreds of performances.”

Dr. Leroy Storsley, the director of the Living Kidney Donor Program at HSC Winnipeg, credits Small and Wilson with bringing hope to people and raising awareness.

“Just last year, the Kidney Paired Donation program reached 1,000 kidney transplants, which included 66 Manitoba pairs like Alan and Jill,” Storsley said. “This remarkable milestone would not have been possible without this collaborative program, the kindness of living donors and recipients willing to participate.

“By being able to share their journey to living donation through the pages of the Free Press, Alan and Jill revealed the process to people in a down-to-earth manner using honesty and humour.

“Starting conversations about living donation can be difficult. Features like theirs provides a window into what living with kidney disease can be like and the wonderful gift that living kidney donation can offer.”

Wilson said the newspaper will never find a replacement for Small and his co-workers will never forget him.

“He was a colleague, but more than that, he was a friend,” she said.

“His work here will be missed, but Al himself will be so missed. We shared a special unspoken bond.”

kevin.rollason@winnipegfreepress.com

Kevin Rollason

Reporter

Kevin Rollason is one of the more versatile reporters at the Winnipeg Free Press. Whether it is covering city hall, the law courts, or general reporting, Rollason can be counted on to not only answer the 5 Ws — Who, What, When, Where and Why — but to do it in an interesting and accessible way for readers.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.