Ah, summer.

Beaches, porches and the great outdoors. Hot days, glorious sunsets and lazy highway drives.

As we head into the July long weekend, we asked several Free Press writers to muse on a slice of a Manitoba summer, be it a destination, a distant memory or a sensory delight. It turns out we’re big fans of ice cream and rural movie joints.

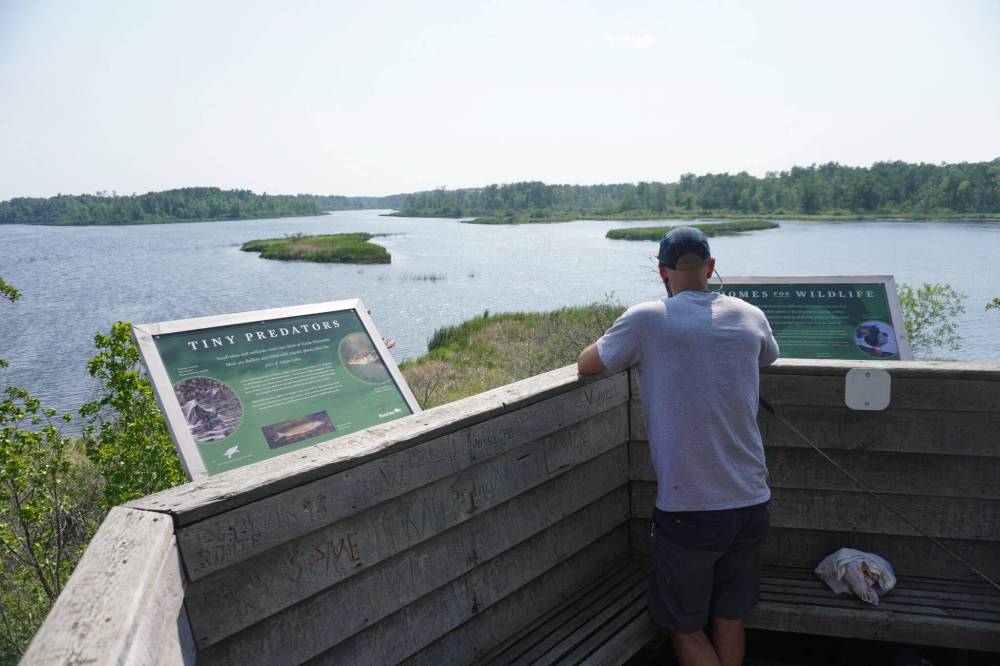

Travel west and as far south as you can without leaving the province and you’ll find a sweet little campground with a swampy swimming hole and hilarious hiking trails.

Adam Lake holds the beating heart of my summer.

Located in Turtle Mountain Provincial Park and surrounded by other anthropomorphic lakes — Katie, James, Emma — the Adam Lake recreation area opened in 1973. My partner and I found it during a game of campsite roulette in 2021 and have made a sojourn every summer since.

EVA WASNEY / FREE PRESS

Adam Lake is a peaceful getaway in the southwest corner of the province.

While the campground itself is lovely — paved roadways, large private sites — my favourite spot is a reedy strip of land at the bottom of a treacherously steep walking path, sandwiched between the lake and human-made swimming area.

Time passes slowly there. The water is always still. Birds, frogs and dragonflies make their home on the marshy shore. The benches along the small isthmus are ideal for late-night philosophizing.

The land bridge also serves as a gateway to some charming features: a lakeside trail to the unserviced and equestrian campgrounds (I have yet to see horses there, but it’s on my bucket list); a canoe launch and a wildlife observation tower.

The weirdest and most wonderful surprise, however, was the two-kilometre “fitness trail” dotted with aging wooden balance beams, log lifts and chin-up bars. I’m sure you could actually get a decent workout if you did the circuit in earnest, but I’ve only ever experienced a sore stomach from laughter.

Adam Lake holds the beating heart of my summer: approachable outdoor adventure, bountiful wildlife and oddball amenities.

— Eva Wasney, Arts & Life writer

There’s no food like summer food.

Flaky pickerel at a shore lunch. Mini doughnuts at the fair. Roadside-stand cherries and peaches at the beach. A hot dog at the baseball game. Buttery corn on the cob at the barbecue.

You don’t even need to travel to be transported somewhere else, so powerful is the link between flavour and memory — and summer flavours are particularly potent.

Which is why my destination is not a sleepy small town or a particularly stunning Prairie vista. It is a literal gas station.

Specifically the Brandt Street Co-op Gas Bar in Steinbach, which just so happens to serve up a treat that is both a true taste of summer and a decidedly Manitoban delicacy. And that is the Mennonite Sundae.

It’s a simple concoction: a heaping portion of vanilla soft serve topped with maple pancake syrup and shelled sunflower seeds. It’s more delicious than it has any right to be — the perfect combination of salty and sweet.

Now, sure, you could recreate this at home. But then it wouldn’t come in a Co-op-branded cup in a portion size that could feed a family, and that is part of the experience.

The Mennonite Sundae at the Brandt Street Co-op was an off-the-beaten-path reader suggestion that Erin Lebar and I received for our popular Rural Eats series we did a few years back. So not only does it remind me of summer, but it reminds me of a summer road trip discovering all the culinary delights our province has to offer.

— Jen Zoratti, columnist and feature writer

Every summer since I could sit upright, I’ve done so in a seat at the Gimli Theatre, the one and only silver screen in the beachside town one wavey creek north of Winnipeg.

Tied with the Dave Barber Cinematheque and the late, great Towne Cinema 8, it’s my favourite place to see a movie in Manitoba. Just look at the sign out front, with its unspooled reel and the diagonal red lettering spelling out “theatre,” and try to resist being charmed into buying a ticket.

My earliest movie memories take place in that house Harry Greenberg built, which showed its first flick in January 1947.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

The Gimli Theatre has been a mainstay for more than seven decades in the Interlake community. The first flick hit the screen in 1947.

The first movie I can 100 per cent confirm I saw in the theatre was 2003’s Finding Nemo, which was also my first exposure to a personal comedic hero in Albert Brooks. The auditorium was packed, with every seat sold out. Gimli being a lakeside town, patrons brought in folding beach chairs to set up at the back of the theatre, and in what might have violated occupancy and safety codes, dozens of us watched from the aisles.

I saw the movie with my dad and sister, but my mom, who never liked to sit still, also came. That was a big deal.

As someone who now writes theatre reviews, consider all this a rave. The Gimli Theatre is the place where I was first moved by motion pictures, and every summer, I thank the stewards of that institution for keeping Harry Greenberg’s cinematic dream alive nearly 80 years after the flash of its opening credits.

— Ben Waldman, Arts & Life writer

To me, a perfect Manitoba summer evening is spent cycling on gravel roads and grabbing an ice cream at The Kiln.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

A kid-sized vanilla soft-serve cone at the Kiln drive-in in Stonewall.

Located a 15-minute drive north of Winnipeg’s city limits, The Kiln Drive-In in Stonewall is where people from all corners of rural life come together. Parents bring their kids after softball games, Hutterite families travelling in big vans stop in, farmers head there for a bite and seniors bring their dogs. Everyone gets a treat — canines included.

I’m new-ish to the Prairies and there’s something that feels quintessentially “Manitoba” to bike along dusty roads at sunset, each mile bringing a new crop of golden sunflowers or purpley-blue flax or bright yellow canola. I sometimes spot a giant rabbit or ground squirrel sprinting across the road, and there are almost always deer.

The Kiln is the ideal spot to end a bike ride, beckoning you with its cheeky signage: “A balanced diet is an ice cream in both hands!”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

The Kiln Drive-In in Stonewall is where people from all corners of rural life come together.

Their menu has enough options to overwhelm a newbie, but my go-to order is chicken fingers with honey dill sauce with a vanilla milkshake or Reece’s Pieces “Twister”— their take on a McFlurry or DQ Blizzard.

If you’re lucky, you’ll get to witness kids gleefully feeding their dogs The Kiln’s tiny ice-cream cones on the outdoor patio. Pooches gobble down vanilla soft-serve. Toddlers order the same size cones.

The Kiln is a spring-to-fall operation only, making summer trips there all the more sweeter.

— Katrina Clarke, investigative reporter

A line of longitude exists, even though you really can’t see it.

Ever since I was a young boy travelling along the Trans-Canada Highway, the existence of 97°, 27’28.41 west has caught my eye.

Initially, my interest was tied to the natural desire to search out my place in the world around the same time elementary lessons in geometry were introducing me to latitude and longitude. The stone cairn just off the highway west of Headingley marking the Principal or First Meridian led me to believe this Prairie boy really was where it all began. Literally.

That seemingly invisible north-south line was the very foundation of the Dominion Lands Survey System. Since 1869, every other meridian that came afterward across a quarter of the continent was numbered westerly and easterly from that line of longitude.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS

The Principal Meridian Cairn marks the foundation of the Dominion Lands Survey System.

In my young mind, where I lived mattered because that line mattered in ways that shaped the layout of our nation.

Of course, as I grew, so did my horizon. In short order, I no longer needed my proximity to an imaginary line, whose historical significance is noted on a bronze plaque, to feel important.

That Meridian, however, still has a hold on me because its path cuts through land my grandparents farmed along Highway 2, about 20 kilometres south of that stone cairn. It’s a line that reminds me of a quarter section full of memories of time spent on tractors, the thrill of being in the cockpit of a small airplane with my grandfather on flights that began and ended on a runway carved next to a wheat field and, of course, grandma’s homemade apple pie.

Whenever I drive that stretch of the Trans-Canada, I look forward to passing that stone cairn because it reminds me to look directly south toward a piece of land foundational to me, to reflect on a line linked to my lineage.

— Paul Samyn, editor

In John Cheever’s classic short story The Swimmer, middle-aged suburbanite Ned Merrill sets out on a quest to swim his way home, one backyard swimming pool at a time.

I think of Ned as I look out my front porch window into the porch of my next-door neighbour, and the porch next to that, and the porch next to that, and wonder if I could embark on a similar journey home through Wolseley.

For seven months of the year, as Winnipeg endures its annual freeze-thaw cycle, the porch is a place to pass through, not to stop.

By late spring, each morning starts with the same ritual opening of the front door and the question: is it warm enough yet to sit in the porch?

Summer is here and the answer is: Oh, yeeeeaah!

KAREN GOODRIDGE / FREE PRESS

The porch is that space where the border between house and outside world blurs or disappears altogether.

To look at it, our porch space is nothing special: a couple of comfortable chairs dusted by the street grime that blows in regularly through our porous window casings, and a thrift store-wooden chest/table to set your feet on.

But for the few precious months that allow it, our porch is the place to bookend our days, a place to share a morning coffee and newspaper with my partner or cap off the night with a candle-lit tea (or something stronger) and a light strum on the guitar.

The porch is that space where the border between the house and the world outside blurs or disappears altogether, that sweet spot where you feel part of the stream of life around you, without having to leave the comfort of your chair.

Is it time to go already?

— Dean Pritchard, courts reporter

“Guess what crop is growing in that field,” says my dad as we roll along Highway 3 toward Morden.

We play the car game every summer as we make our way to the Stardust Drive-In Theatre.

It’s a race against dusk to arrive before for showtime, but we soak in the pink Prairie sunset, and succumb to the promise of summertime nostalgia.

When the car rolls off the blacktop and onto the gravel, queuing up for the ticketing booth, someone instinctively changes the radio station to 88.5FM to tune into the movie previews.

Tickets in hand, a seasonal employee gives us a menu for the concession stand — although our order has never changed: a bucket of buttered popcorn, with two bags of peanut M&Ms dumped in.

Melissa Tait / Free Press files

The night sky is often a part of the show at Stardust Drive-In in Morden.

Below the stars on a gravel parking lot, the theatre’s commanding white screen helps you forget about the smattering of bugs on the windshield.

If the weather’s nice and the mosquitoes aren’t ravenous, we pull out the lawn chairs from the trunk and unfold them beside the open window of our car.

Sitting outside to soak up the film isn’t uncommon: other moviegoers often opt to open up the hatchback of their vehicles, load the bed of their truck with a mattress, pillows and blankets, or even bring an entire couch to lounge on.

While the theatre is known to air the occasional triple feature, a visit on a clear night during the Perseid meteor shower guarantees a double.

Now, sit back, relax and enjoy the show.

— Nadya Pankiw, multimedia producer

I come from a family of small-scale excursionists. We were not big vacation-takers, but went on long evening drives almost daily in the summer, which usually ended in ice cream and parking somewhere far from Winnipeg’s inner-city, after which my siblings and I were expected to take in whatever nature view my parents had settled on and be sufficiently moved by it.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

Skinner’s restaurant in St. Andrews touts itself as the oldest hot dog venue in Canada still running today.

I remember being immensely bored by these journeys growing up. I don’t know if I ever “got” what my parents were hoping we’d get out of those drives until we pulled up to the Skinner’s drive-in in Lockport (the one on River Road, although there is another one just a few minutes away on Highway 44), got ice cream and took in the view.

Skinner’s itself is a piece of Manitoba history — it’s 95 years old and touts itself as the oldest hot dog venue in Canada still running today — but I was amazed, both back then and today, by the dam just steps away.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

The St. Andrews Caméré Curtain Bridge Dam is an engineering marvel. It’s likely the only remaining dam of its kind in the world.

The St. Andrews Caméré Curtain Bridge Dam is a national historical site and a feat of engineering unlike anything else you can see anywhere and — according to Parks Canada — the only surviving movable dam of its kind in the world. It was opened in 1910, a time of expansion and innovation in Winnipeg, and brought to North America a unique European style of dam that used movable curtains in hopes of managing the Red River’s powerful floodwaters and making it navigable.

Today, I make the trip a few times a summer, grab Skinner’s fries (too lactose intolerant for the ice cream these days), and find a spot to watch the river move and the boaters seek catfish. It’s a small-scale excursion — maybe 20 minutes out of the city — but it’s also a stunning reminder of how we all got here, and how crucial water, be it passing through the dam or coming from Shoal Lake, is to our province.

— Malak Abas, general assignment writer

The sunroom. The porch. The veranda. The summer kitchen. The dining tent. Whatever you call a room with screens for walls, it’s the best place to enjoy a Manitoba summer.

WENDY SAWATZKY / FREE PRESS

Whatever you call a room with screens for walls, it’s the best place to enjoy a Manitoba summer.

At my house, we call it the gazebo. As soon as the snow melt permits, we’re drawn to this extension of our living space — and we continue to delight in our backyard haven well into autumn, even if it means layering up with a couple of sweaters.

In the spring, the morning sun gently warms the space, making it the perfect spot for a quiet coffee. On hot August evenings, a cool breeze offers a refreshing respite. When the weather turns inclement, the pitter-patter of a cloudburst — or even the rumble and flash of a thunderstorm — provide prime entertainment from the shelter of the gazebo.

The gazebo lets me take in the best sounds and scents of the outdoors — birdsong, barbecue, freshly mown grass, children’s laughter — while still taking advantage of the civilized benefits of the indoors. Tackle the crossword in the newspaper (without pressing it into service as a flyswatter!), sip a glass of wine (without hovering wasps!), hang out with friends (without the awkward jig of skeeter-avoidance!).

Did I mention there’s no pesky insects??

At the lakeside, deep in the woods or in an urban backyard, nothing tops a screened room during a Manitoba summer. It’s a seasonal slice of heaven that can’t be beat.

— Wendy Sawatzky, associate editor — digital

It could’ve been an Agatha Christie title: Murder in the Blue Hills.

It could’ve been, if there was a murder.

It’s easy to think something nefarious took place. And one’s mind does tend to wander as the trail meanders. How else to explain the presence of a sky-blue Volkswagen Beetle — pockmarked with bullet holes and scarred with rust resembling dried splatters of blood — in the middle of nowhere? It’s a mystery, for sure.

SCOTT GIBBONS / FREE PRESS

Wander enough in the Brandon Hills and you’ll find the abandoned Volkswagen Beetle. There’s no shortage of trails to keep you occupied in the meantime.

The river valleys cut deeper on the western side of the province, the land rises and falls like a sleeping child’s chest. And the gravel roads? They tend to break from the usual square-mile precision by tossing a few curves a motorist’s way.

It’s here where the Brandon Hills are situated, about 10 kilometres south of Manitoba’s second largest city and my hometown, drawing hikers, trail runners, cyclists and skiers year-round.

They’re more evocatively known as the Blue Hills of Brandon due to their distant summertime hue. Originally formed by glaciers, the long ridge stretches for several kilometres east to west.

It is home to the Brandon Hills Wildlife Management Area where dozens of rolling single-track trails crisscross the oak and aspen forest. Nearly each junction is marked by an easy-to-follow map, making it impossible to lose your way. The wildlife management area is also where you might find the aforementioned Volkswagen.

I haven’t lived in Brandon for years, but one western Manitoba destination has been calling me back in recent summers. It’s no mystery as to why — the Blue Hills boasts one of the best networks of trails in the province.

And if you do happen upon the abandoned Beetle, feel free to let your imagination run wild.

— Scott Gibbons, associate editor — enterprise

The acrid scent of gunpowder wafts up toward the sweat on my brow, and the plate of the shotgun kicks slightly into my shoulder, before the pellets from the 12-gauge shell shatter the clay pigeon flying low ahead of the berm, across the flat ground too-often littered with the spent casings of others who came before me.

It is a summer day in Manitoba, and if the weather is right — not too windy, and ideally, hot — I’m at ranges near the ponds in the Rural Municipality of Reynolds, where friends and I have set up targets and old cans for our .22 rifles and brought out clays to toss for our shotguns.

ERIK PINDERA / FREE PRESS

The Reynolds Ponds are a little-known gem not too far from Winnipeg.

A sharp turn off the Trans-Canada at Forestry Road 13, not far from Richer, Reynolds Ponds are not quite a hidden gem — with the ponds, shooting ranges and trails too-often littered with refuse from impolite guests — but the area and its decommissioned quarries remain an oasis for those looking for an out-of-the-way but not too far place to enjoy the outdoors. The area offers a place to swim in opalescent waters, to fish the stocked ponds, target shoot at the homemade ranges or ride off-road.

But make sure to clean up — and regulate yourself — lest the ponds, which sit on Crown land, get privatized, as the RM’s reeve publicly mulled in 2022. The reeve also suggested turning the area into a provincial park to better regulate visitors.

Regardless of its future, the call of the outdoors in this corner of the province is often too much to resist as the temperature rises.

— Erik Pindera, justice reporter

There are articles about Steep Rock that list 10 reasons to visit but I only needed one: the beach. I love swimming and lazy days on the lake, so as soon as I saw photos of those limestone cliffs and dazzling turquoise waters, I knew I had to go.

Shel Zolkewich / Free Press files

Steep Rock Beach Park is a one-of-kind Manitoba destination.

I first visited in August 2020. Weren’t we all tourists in our own province that first pandemic summer? That’s part of what makes Steep Rock Beach Park so special; as someone who frequents Lake Winnipeg locales like Patricia Beach, making the journey to the northeastern shore of Lake Manitoba feels like leaving the province without actually leaving the province.

My wife, our siblings and I made the 230-kilometre trek up Highway 6 with a picnic lunch and a pizza slice-shaped floatie packed in the trunk. It was a flawless summer day, full of laughter, sunshine and swimming — the perfect escape from whatever COVID-19 anxiety we were feeling at the time.

I’ve become a Steep Rock evangelist since then, spreading the good news about this fantastic place whenever I can. Often when I mention it to people, they’ve never heard about it — even if they’re lifelong Manitobans. Maybe they’re homebodies like me who don’t get out much. In any case, that’s another thing that makes Steep Rock special: it feels like a secret I need to share. So go, and I hope you enjoy it as much as I do.

— Aaron Epp, business writer

Every year when my parents would pick up me on the last day of summer camp, there was always one thing for certain: we would stop at Syl’s Drive Inn.

By the time we arrived, there was already a packed parking lot and a line of other families wrapped around the red-and-white building. The chatter of campers eager for a greasy cheeseburger or an ice-cold milkshake could be heard from the street as the Prairie sun would set on Carman.

TERESA GIBBONS / FREE PRESS

For kids heading home from summer camp, a stop at Syl’s Drive Inn in Carman was always a must.

While waiting in line, I would spot my favourite camp counsellor, grabbing their own order of delicious Syl’s goodness, and chase them down for one more emotional goodbye. Parents would laugh and joke as they compared notes on how they spent their week child-free.

Somehow my week-long camp sunburn made the vanilla ice-cream cone I ordered taste even sweeter and cooler.

Campers exchanged phone numbers, mailing addresses and emails so they could stay in touch during the months before reuniting at next year’s summer camp. Everyone waited in anticipation for their number to be called over the loudspeaker, bringing them one digit closer to the food they craved.

Syl’s served as the last summer camp stop where the memories of friendships made were relived one last time.

After clambering into our family minivan, with sticky hands from melted ice cream, I would fall asleep on the drive back to Winnipeg, dreaming about next year’s camp and the ice cream cone that would surely follow.

— Matt Frank, Free Press intern

There’s nothing seemingly remarkable about a last-stop gas station before cottage country, but one seems to be on the radar of many weekend warriors without realizing it.

The Wavers of Brokenhead convenience store gas station in Scanterbury, located about 60 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg at the southern edge of Lake Winnipeg, may be a passive stop on Highway 59 for cheap gas to some, but to others it signals the beginning and end to a weekend spent at the cabin, and a memory of a beloved pair of men.

There’s something both nostalgic and brand-new about the warm smiles of attendants, grabbing a slice of greasy pizza from the gas station’s adjoining Chicken Delight or a scoop of bubblegum ice cream, all while resisting the urge to hop next door to the Miami-esque South Beach Casino and try your luck.

Marc Gallant / Free Press files

For years, brothers James (left) and Nelson Starr waved to families heading to and from the cottage as they passed through Brokenhead First Nation.

A stop at Wavers, located within Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, wouldn’t be complete without a visit to the big red-and-white Adirondack chair dedicated to beloved locals James (Jimmy) Starr and Nelson Starr, the two men who spent decades waving to cabin-goers from their lawn chairs parked right off the highway (and for whom the fuel station is named in honour).

As the youngest in a family of six who spent summers in Lester Beach, my core memories from summer weekends don’t drift to splashing around in lake water (pre-algae and zebra mussels), but rather to my rag-tag group of siblings and me in the back of our family’s cherry-red Ford Aerostar, waiting to hit Scanterbury.

When the men appeared on the horizon, my siblings and I would get as close as we could to the front windows without falling out, feverishly wave our arms to the unknown, yet all-too-familiar men, before continuing our journey down the highway like we always did, and would continue to do, long after they were gone.

—Nicole Buffie, multimedia producer