It’s Bombers’ game day and thousands of fans clad in Blue and Gold are descending on Princess Auto Stadium from all corners. It’s a noisy, somewhat hectic affair as the team’s faithful arrive on buses, cars, bicycles and foot.

While stadium staff direct traffic, a Winnipeg police officer stands alone amid pylons at a blocked-off roadway looking at his phone.

Inside, uniformed police are weaving their way through the sold-out crowd. Some are positioned close to the rowdy Rum Hut, while others plant themselves at the edge of the field, eyes glued to the sea of spectators in front of them.

The officers are not working a regular shift, despite how they appeared to the public.

This is “special duty” policing, a controversial practice that shows no signs of abating.

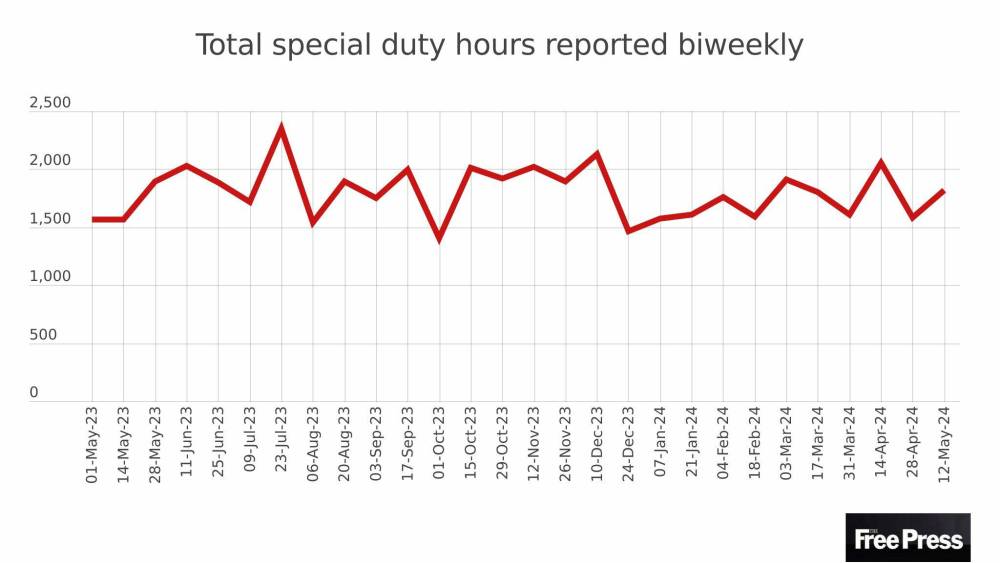

Winnipeg police officers spent more than 50,000 hours doing special duty work — racking up millions of dollars in fees in the process — over a 13-month period from May 2023 until June 2024, according to data obtained by the Free Press.

That’s equivalent to 6,393 regular eight-hour police shifts.

It is overtime work picked up on a voluntary basis and typically paid for by private companies, but also by public bodies using taxpayer dollars.

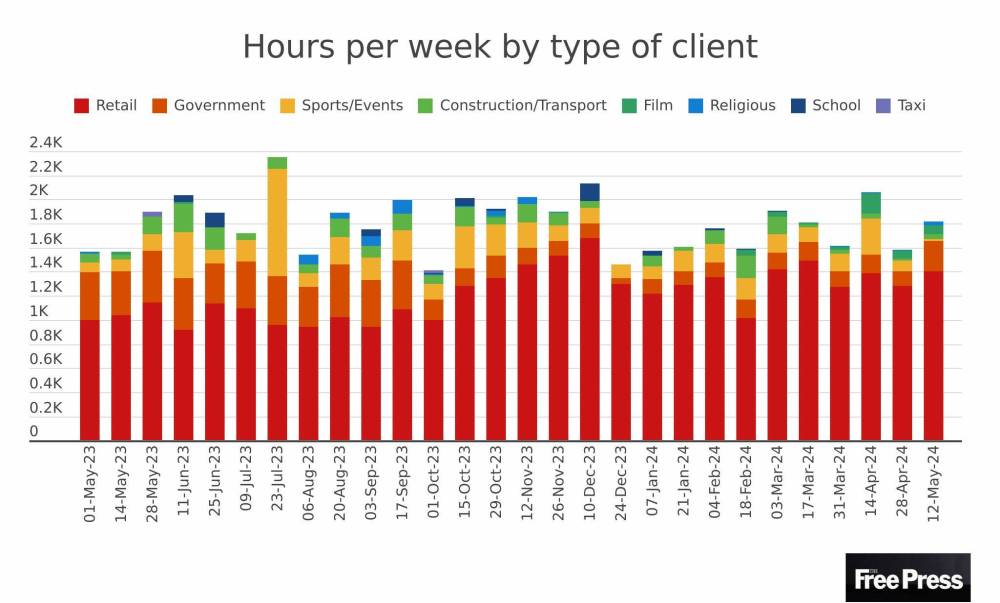

The work can include everything from directing traffic outside a church or along a marathon route, to supervising a high school grad or film set, to thwarting would-be shoplifters. Retailers were responsible for 68 per cent of the 50,000 hours tracked by the Free Press.

While special duty, also known as “paid duty” or moonlighting, has long been part of police work in Winnipeg, critics say it tarnishes police force reputations, adds to officer burnout and indirectly siphons off public dollars.

It’s also a touchy subject.

Elected officials were reluctant to weigh in when the Free Press sought comment on the 50,000 hours of overtime. Email responses to our queries were vague or delayed and were filtered through spokespeople.

Winnipeg Mayor Scott Gillingham, however, said he is “open” to changing the city’s position on hiring special duty officers. He also acknowledges there has been “a lot” of special duty policing in recent years and that he expects police management to ensure the program is administered responsibly.

Officers, meanwhile, defend the work, saying it’s a good gig that allows them to earn extra cash and perks outside the confines of an otherwise stressful job.

Debate about the practice is intensifying as Winnipeg police brass argue they desperately need more officers, saying the force is burnt out from working overtime — however, not special duty overtime.

That, the police union argues, is fine.

Kevin Walby, an associate professor in the department of criminal justice at the University of Winnipeg, calls paid duty a “cash cow.”

“This is just like having a second job, it’s so lucrative,” said Walby, who, with the University of Windsor’s Randy Lippert co-authored the 2022 book Police Funding, Dark Money, and the Greedy Institution, which looked at special duty policing across North America.

Walby said it’s enticing for officers to earn time and a half doing work that is typically less strenuous than their regular-duty responsibilities.

“Police would like to say that they’re doing important stuff when they’re on paid duty, but they’re not,” Walby contends.

To hire one constable for an hour of moonlighting, the Winnipeg Police Service charges $128 plus GST, with rates going up depending on rank. There is a three-hour minimum booking requirement. Part of the fee goes to the officer doing the work, but the police wouldn’t provide the exact breakdown, only saying that the surplus money it receives goes toward the program’s operating costs, including wages, benefits and administration.

KATRINA CLARKE / FREE PRESS

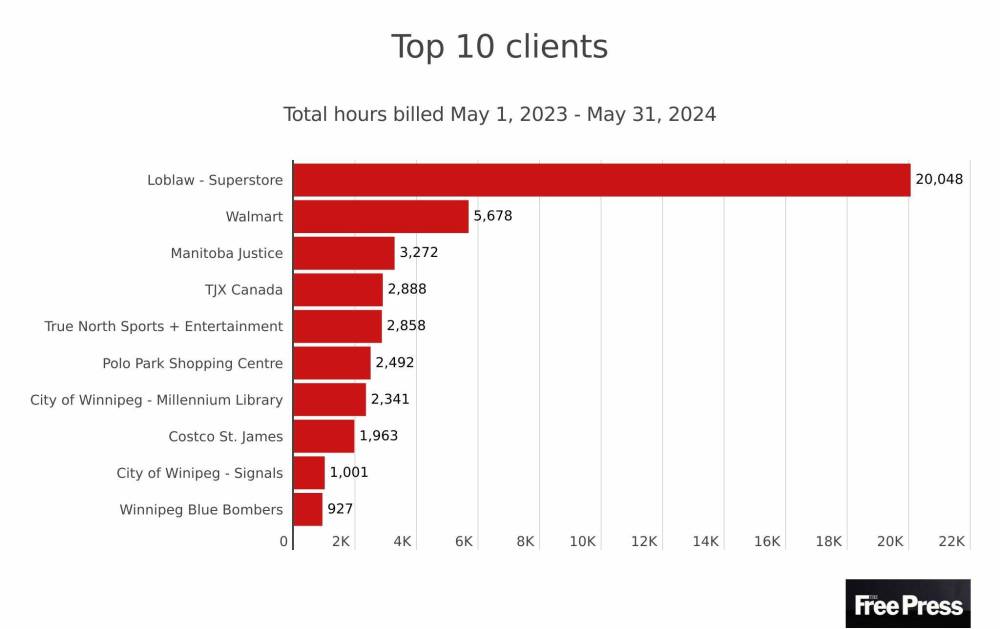

Loblaws’ Superstore was the top biller for special-duty policing in Winnipeg, racking up more than 20,000 hours — or about 40 per cent of the total tracked.

According to the collective bargaining agreement, a constable’s base salary ranges from $65,000 to $130,000 annually, or $31 to $63 an hour, meaning they earn between $46 and $94 for every hour of special duty.

The force expects to collect $7.3 million in revenue from special duty policing this year. In 2023, it was $6.7 million, police said.

Asked if there are limits to how many hours officers can work in a single shift, the police service said restrictions are in accordance with operating guidelines that reflect the collective agreement. The police denied a request by the Free Press for those operating guidelines.

The collective agreement stipulates that officers are not eligible for “extra duty” if the assignment starts or ends within eight hours of their regularly scheduled shift. Officers who want extra work put their names forward and are chosen in order of seniority.

Walby questions why police — trained at taxpayers’ expense — are needed at sporting events or on film sets. Even in grocery stores, where officers have been hired ostensibly to prevent theft, their role is murky, he said.

He regards them as “highly paid scarecrows” — perhaps deterring would-be thieves with their armed presence, though able to intervene if a crime occurs.

“It leads to public views of police as ‘cops as props,’” he said.

“It leads to public views of police as ‘cops as props.”–Kevin Walby

That’s a perspective the police want to avoid, said Winnipeg police Supt. Dave Dalal.

“All officers act only within their duties as a police officer,” Dalal told the Free Press in an email. “They are not doing store security work. One of our requirements is that the retail location has an LPO (Loss Prevention Officer) so that we are not drawn into security duties.”

So, what do special duty officers do?

Deter crime and support security guards when they believe someone has committed a crime, Dalal said.

According to the data obtained by the Free Press, Loblaw’s Superstore was the top biller, racking up more than 20,000 hours in special duty policing — or about 40 per cent of the total tracked — followed by Walmart Canada (5,700 hours) and Manitoba Justice (3,300 hours).

While the data does not include the amount charged to each customer, a Free Press analysis based on the lowest possible hourly rate — $134.40, GST included — suggests Loblaw shelled out at least $2.7 million for the service.

In a statement, Loblaw said it uses off-duty police and other “tools” to deter theft and violent encounters and to keep customers and staff safe. The company did not provide an answer when asked how much it spent on off-duty policing, nor if the amount offsets the cost of stolen merchandise.

Five of the top users of special duty policing were retailers. In addition to Loblaw, they are Walmart, Polo Park, TJX Canada (Winners/Homesense/Marshalls) and Costco St. James. Their use of special duty policing falls outside the provincial government’s current initiative targeting violent crime and retail thefts, which involves funding regular overtime for police.

At a city Superstore on a recent Sunday, a WPS police officer stood amid boxes of Halloween candy, making small talk and smiling at customers as they walked in. Another police officer was pacing in the self-checkout area, routinely scrolling on his cellphone.

“All of the staff here are relieved when we show up,” one officer said. “It’s a good gig, but it’s hard on the feet.”

She said picking up extra shifts helps pay the bills as the cost of living goes up.

Three of the top 10 billers were public bodies — Manitoba Justice with 3,300 hours and the City of Winnipeg twice, with 2,300 hours for the downtown Millennium Library and 1,000 for “signals” work.

It is unclear why the justice department hired so many special duty officers. A spokesperson said: “The province engages WPS special duty selectively for special events and when there is a need for a dedicated police presence.”

When asked to clarify what constitutes “special events,” the spokesperson said “COVID” and “security at special events.”

They also cited a dated example from 2021 that involved hiring a special duty officer during protests and a subsequent encampment at the legislature.

The province wouldn’t divulge how much was spent, but the Free Press analysis suggests it was at least $440,000.

The city, meanwhile, confirmed it spent approximately $450,000 on special duty officers at the downtown library between January and September 2023. The police presence was initiated amid concerns about violence and safety following the stabbing death of 28-year-old Tyree Cayer on Dec. 11, 2022.

The city initially directed questions about “signals” to the WPS before providing a response.

City spokesperson Kalen Qually said the traffic signals division calls in police when they need help directing traffic, such as in cases when lights are out due to repair, replacement or installation.

When asked why a city flag worker couldn’t perform those duties, Qually cited a section of the Highway Traffic Act, stating that while a flagperson, or even a sign, can be utilized, police can also be used.

“It is standard and reliable practice to employ the skills and training of peace officers to do traffic control, whether it’s for an emergency or to ensure the safe uninterrupted flow of traffic,” he said.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS FILES

Special-duty assignments alone are not causing officer burnout, the police union says.

Gillingham, however, says he’s “open” to change.

“While I’m open to other options, I think it’s important though that we have people with traffic control training to do the work,” he said in an interview.

He also said he would speak with the traffic signals department about alternatives.

Lippert, the professor of criminology at the University of Windsor who co-authored the book on special duty policing with Walby, questions why the city wouldn’t employ flag people at a fraction of the cost.

“What are they actually doing at these sites?” Lippert asked.

Walby, meanwhile, says the city should conduct an audit of special duty policing. When the City of Toronto audited its police force’s program more than a decade ago, it found it was wasting millions of taxpayer dollars annually.

Gillingham said it’s important to make sure taxpayer dollars are being properly spent but did not commit to an audit.

The city referred questions about bylaws requiring special duty officers to be on site at events or locations to WPS. The police service, in turn, cited bylaws relating to parades.

The Free Press asked several of the private entities hiring special duty officers if there were rules or laws requiring them to have police present, as opposed to security guards, but none could point to any.

Kenny Boyce, the City of Winnipeg’s manager of film and special events, said in an email that if a film shoot requires traffic closures or limiting pedestrian access to an area, police are hired “to direct traffic and support filming sequences as needed and required.”

The Pembina Trails School Division said one high school hired special duty police for a basketball playoff game, while some parent committees hire them for safe grads, though the division does not have a specific policy on the practice.

The police, however, have rules outlining when they can’t be hired. Those circumstances include:

- a labour dispute; a requirement to perform non-police duties;

- an unacceptable risk or threat of injury, such as an insufficient number of police personnel requested;

- an event where those affiliated with the event have criminal associations;

- an event that promotes confrontation between groups; and

- liquor license establishments or where alcohol is the predominant source of income, excluding events such as concerts or socials assessed as “high risk.”

Special duty police are often visible at large sporting events, such as Bombers’ games.

At a recent home game, at least eight police were present, with four stationed on the edges of the field, staring intently at the packed crowd for the full three hours. One broke concentration only when the team’s mascot started waving at him. Others walked around the stadium, speaking with attendees and occasionally watching the game.

“Every job has its perks,” said one police officer.

He said the police’s role is to “augment” security, stepping in when needed.

Kelly Keith, director of security for the Bombers and a former Winnipeg police officer, said around 16 special duty police are on site at sold-out games, which have 32,000-plus people in attendance. They do crowd control inside, possibly direct traffic outside, and take over any matters that might rise to the level of criminal activity — drunken brawls included.

It’s not so much that the Bombers are required to have police on site, but more of a responsible safety move, he said.

Keith recalls picking up special duty shifts when he was an officer. If there was something he was interested in, he’d sign up. It was a good gig getting paid to do your job while attending an event you enjoyed, he said.

Approximately 125 clients are included in the 13 months of data tracked by the Free Press, including more than a dozen high schools, the Manitoba Marathon, eight film-related events and upwards of 30 construction or transportation companies.

Walby takes particular issue with one top biller: the World Police and Fire Games.

The event attracted 10,000 police and fire members from around the world to compete in an Olympic-style event in Winnipeg in late July and early August 2023. According to the data, the event billed for 781 hours of special duty work at a cost of roughly $100,000, according to the Free Press analysis.

“Why do you need a bunch of police standing around to protect a bunch of police?” Walby asks.

His concerns are heightened knowing how many public dollars were involved.

The city contributed $1.5 million and nearly $1 million in the form of a “value-in-kind” grant — police say the cost of paid duty came from this grant. The former provincial Tory government put $4.9 million towards the event and the feds chipped in $2 million.

“It’s an abuse of public funds,” Walby said.

Meanwhile, Winnipeg police leaders are sounding the alarm about traditional overtime.

A September budget update reveals overtime costs for regular policing are expected to hit $11.8 million this year, a 50 per cent increase over last year.

“(It’s) not (sustainable) from a cost perspective, nor from a mental health perspective for the officers … It does have an impact on their mental health, it does have an impact on their work-life balance, and we’ve got to be mindful of that,” police board chair Coun. Markus Chambers recently said.

The police service’s interim chief Art Stannard has said that amid increasing demands on the service he’d like to see 78 more officers hired.

“We worry about their well-being. They’re overwhelmed,” he said.

But where does special duty fit in? Doesn’t it also lead to burnout?

“It is not special duty assignments alone that could result in increased levels of burnout,” said Cory Wiles, president of the Winnipeg Police Association, in an email.

“I say that because most often the special duty assignments are on officers’ days off as opposed to the more immediate concern, the unwanted overtime at the tail end of an already lengthy shift.”

“Most often the special duty assignments are on officers’ days off as opposed to the more immediate concern, the unwanted overtime at the tail end of an already lengthy shift.”–Cory Wiles

Walby pushes back on the union’s position.

“I think it’s disingenuous to say the force is so tired (but not from special duty),” he said. “I personally think that these are games that police executives play.”

Chambers refused to comment for this story, saying special duty policing is an “operational” matter.

As for who sets the wage rates, it’s police.

In September 2020, the city’s executive policy committee recommended that authority to increase fees for special duty policing above inflation be delegated to the Winnipeg police chief. Council approved the motion.

Analysis shows special duty rates went up more than 40 per cent over the past decade. In 2014, it cost $90 per hour to hire a special duty constable, up to $128 today, according to city documents.

“That’s nice, I wish we all had those kinds of raises,” said Lippert.

Gillingham defends the increases, saying prior to 2020, the rates didn’t cover all costs including benefits and pension. Taxpayers were therefore subsidizing special duty, he said, but that is no longer the case.

However, he added: “I’ve asked about special duty policing since 2020 because there have been a lot of hours of special duty policing. I expect the police management to keep an eye on the special duty assignments to ensure there’s good work-life balance for officers and that officers are not becoming exhausted working this special overtime.”

The rates are comparable with those of police forces in similar-sized cities across Canada.

Like Walby, Lippert is concerned about the cost to taxpayers.

He said police are highly trained professionals whose expertise and salaries are paid for by the public. When a private entity hires them, that business is benefiting from investments the taxpayer has made — which can be seen as the public subsidizing private-sector security, he said.

And when the city or province is the client, the public is paying higher rates for services they’ve already invested in, Lippert added.

And there’s another matter: pensions.

Winnipeg police overtime — be it special duty or regular duty work — counts as pensionable hours.

In Winnipeg, the city’s share of pension contributions for Winnipeg Police Association members is around 20 per cent.

“It’s outrageous,” Walby said of the pensionable time for special duty policing. “There is no public benefit at all, but there is a public cost.”

Gillingham disputes this, saying the current rates cover all costs — pension included.

In other large cities, such as Toronto and Calgary, special duty overtime does not count toward pensionable hours.

Former Winnipeg mayor Brian Bowman waged a losing battle trying to adjust police pensions. In 2018, Bowman vocally opposed allowing overtime to count towards pensionable police wages. He estimated that ending the practice could save $1.5 million a year, funds that could be used to hire 10 to 15 more officers.

But when city council voted to change the police pension plan in December 2019, the police union fought back. An arbitrator ruled against the city, finding the action breached the police’s collective agreement.

katrina.clarke@freepress.mb.ca

Katrina Clarke

Investigative reporter

Katrina Clarke is an investigative reporter at the Winnipeg Free Press. Katrina holds a bachelor’s degree in politics from Queen’s University and a master’s degree in journalism from Western University. She has worked at newspapers across Canada, including the National Post and the Toronto Star. She joined the Free Press in 2022. Read more about Katrina.

Every piece of reporting Katrina produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.