A growing number of wrongful convictions have come to light in Manitoba. What isn’t known is how many people in the province are still waiting to be exonerated for crimes they didn’t commit.

A new law could change that.

In February 2023, then-federal justice minister David Lametti introduced Bill C-40, which — if passed — would create an independent commission overseeing miscarriage-of-justice applications.

Called David and Joyce Milgaard’s Law, it was created to remove politics from the system, speed up reviews and eliminate barriers for populations overrepresented in the Canadian justice system.

The current approach is onerous and time-consuming.

First, applications are investigated by a Criminal Conviction Review Group before the federal justice minister decides whether to order a new trial or appeal — a process that takes years.

While many believe the proposed commission is overdue, with multiple separate inquiries into wrongful convictions recommending the need for one, even its proponents say it doesn’t go far enough. Still, they want it passed. Now that the governing Liberals under Justin Trudeau are hanging by a thread, it’s become a race against time.

A snap federal election means it could die.

Lametti is no longer an MP but remains one of Bill C-40’s biggest champions. For him, ensuring its swift passage is deeply personal.

“I try not to get emotional when I talk about this,” Lametti said in a recent interview with the Free Press.

The bill is named for David Milgaard, a Winnipeg-born man who spent 23 years in prison for a rape and murder he did not commit, and his mother, Joyce, who spent decades fighting for his freedom.

Lametti calls Milgaard his hero, and says he promised him the long-called for independent commission would see the light of day.

Joyce Milgaard and her son David are shown outside Supreme Court in Ottawa in 1999. (Fred Chartrand / The Associated Press files)

Neither Joyce nor David lived to see the bill introduced. Joyce died at age 89 on March 21, 2020 and David was 69 when he died on May 15, 2022.

The bill is now with the Senate. As of writing, signs point to it passing third reading, though it would still need royal assent and to be proclaimed.

If an election is called — the minority governing Liberals lost the support of the NDP earlier this year, meaning a confidence vote could trigger one — or if the Senate decides to send the bill back to the House for revisions, Lametti’s best laid plans could be undone.

“I’m worried right now,” Lametti acknowledged during an interview in September. “I’m worried that the government prorogues. I’m worried that somehow they get shot down on a confidence motion that could have otherwise been avoided.”

Lametti’s bill came on the heels of an in-depth consultation overseen by former Ontario Court of Appeal Justice Harry LaForme and former Court of Quebec Judge Juanita Westmoreland-Traoré.

The two sought feedback from people who suffered miscarriages of justice, and from police, prosecutors, defence lawyers, legal-aid officials, judges and forensic scientists.

The 51 recommendations in LaForme and Westmoreland-Traoré’s report were wide-ranging. They included:

- appointing between nine and 11 commissioners, including at least one Indigenous and one Black commissioner;

- implementing better data tracking of applications and their outcomes; t

- hat the commission be headquartered in Winnipeg or Toronto, rather than Ottawa;

- that it be proactive and probe systemic issues rather than be reactive;

- that it pay for applicants’ legal counsel in cases where that would speed the process;

- that it look at both miscarriages of justice and traditional cases where “factual innocence” can be proven;

- and that it provide funding and support to help applicants reintegrate into society.

Government rejected many of the recommendations.

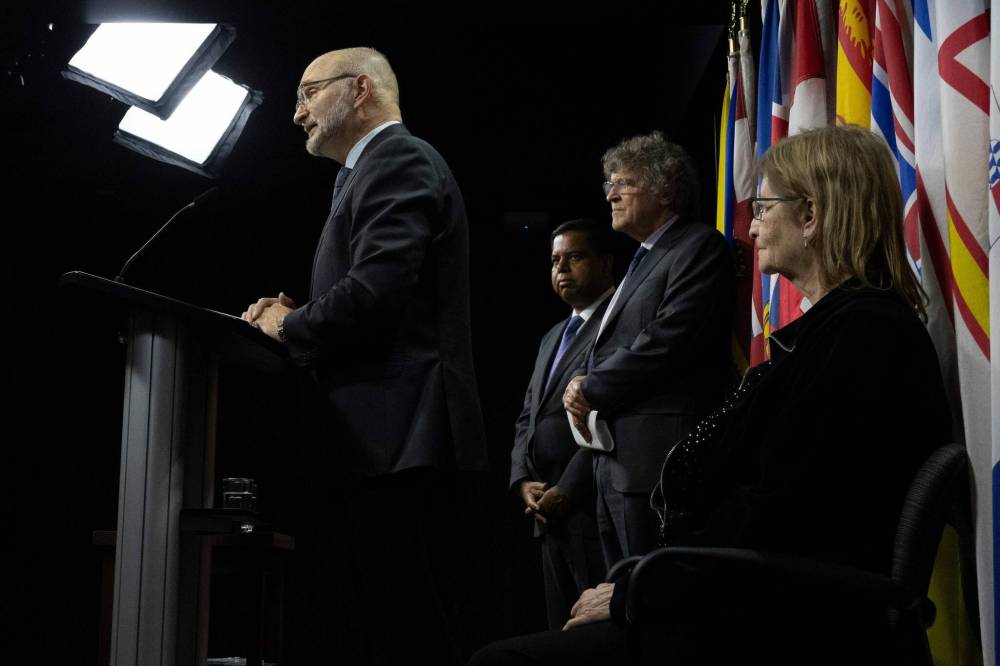

Liberal MP for Scarborough-Rouge Park Gary Anandasangaree, lawyer James Lockyer and Susan Milgaard, sister of wrongfully convicted David Milgaard listen to Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada David Lametti as he announces changes to the criminal code during a news conference on Parliament Hill in 2023 in Ottawa. (Adrian Wyld / The Canadian Press files)

Today’s bill proposes appointing five to nine commissioners with no requirement for any to be Indigenous or Black. It is not limited to probing matters of “factual innocence,” which include cases where someone can be exonerated by DNA evidence, but it’s unclear the extent to which systemic inquiries will be possible.

One major change: in the current system, the minister refers cases back to the courts only when they believe a miscarriage of justice “likely” occurred. The new standard would be that it “may” have occurred, a less stringent bar to clear.

The Liberals say the commission would speed up reviews and remove barriers to access for people who are Indigenous, Black and marginalized.

Lametti’s successor remains committed to seeing Bill C-40 through.

In a statement to the Free Press Wednesday, Chantalle Aubertin, spokesperson for Justice Minister Arif Virani, said the government’s goal is to have the bill receive royal assent before parliament rises for the holidays.

After that, government will move swiftly to create the commission and “ensure a seamless transfer of cases, allowing reviews to proceed without delay once the commission is operational,” she said.

She cast some blame on the Tories for dragging out the bill’s passage, saying they obstructed Bill C-40 at the committee stage with a filibuster.

The consensus among many who work with the wrongfully convicted is that the bill is a step in the right direction, but it doesn’t go far enough.

“Many folks are not very happy with what the government has come forward with,” said Senator Kim Pate, who advocates on behalf of incarcerated women. “They don’t see it as sufficient.”

Among Pate’s concerns:

- the bill will have a limited focus on systemic issues;

- it doesn’t allow reviews of sentences, just convictions;

- it may be underfunded;

- and cases involving marginalized populations, including people who might be more likely to have minor convictions, are still likely to be ignored.

Pate said there is “huge pressure” to make the bill law before the next election, even though sending it back for revisions could improve it.

A common refrain among wrongful-conviction advocates, including Pate, is that the bill is a watered-down version of the comprehensive report by the retired judges.

James Lockyer, a lawyer and founding director of Innocence Canada, a not-for-profit that defends people convicted of crimes they didn’t commit, calls the bill a “tremendous development.” Still, he has questions about how the commission will work in practice.

Among them: who will be on it.

“The identity of the commissioners is obviously very, very important,” Lockyer said. “

I am hesitant, for example, to think that retired judges would be good choices. The reason I say that is that retired judges tend to expect deference and will tend to expect that the other judges will do as they say. And that’s a danger — you don’t need that.”

He also stresses the need for commissioners to have experience handling wrongful convictions, which are complex matters to evaluate.

However, Lockyer remains reassured by provisions in the bill that require the commission to “reflect the diversity of Canadian society” including taking into account the overrepresentation of Indigenous and Black people in the justice system.

Lametti admits compromises were made to ensure the bill passed in the House.

“I think it’s fair to say had I gone with something closer to the Cadillac model that Justices LaForme and Westmoreland-Traoré put forward, there probably would have been more opposition,” Lametti said.

Carrie Leonetti, an associate professor of law at the University of Auckland in New Zealand who has closely followed the issue in Canada, is among those who would have favoured a commission more reflective of the LaForme and Westmoreland-Traoré report, which she calls “visionary.”

“I think a lot of people globally are watching Canada and holding their breath because, God, it would be wonderful if you did what was in that report,” Leonetti said.

“But it’s hard for me to imagine any government, let alone a government coming up for election and behind in the polls, putting the kind of money behind this that it would take, and the proactive systemic vision.”

Commissions in New Zealand and England have also been hamstrung by underfunding at the same time as applications shot up. The New Zealand Criminal Cases Review Commission, established in 2020, received close to double the expected number of applications — 221 versus the anticipated 125 — in its first year.

In Canada, the federal department of justice expects 250 applications in the first two years. (New Zealand’s population is about 5.25 million people, whereas Canada’s is 41.25 million people — eight times larger.)

“I think a lot of people globally are watching Canada and holding their breath because, god, it would be wonderful if you did what was in that report”– Carrie Leonetti, University of Auckland in New Zealand

Leonetti says a lack of resources means commissions have to make tough choices.

“How much of your time do you spend on systemic inquiries and how much of your time and resources do you spend on individual petitions, particularly ones that raise claims of actual innocence?” Leonetti said.

Kent Roach, an expert in wrongful convictions, agrees.

“You want the commission to have enough resources and enough energy and ambition to not only deal with individual cases, but to try to prevent wrongful convictions before they happen,” said Roach, who’s a law professor at the University of Toronto.

He notes New Zealand is undertaking a systemic inquiry looking at whether cross-racial eyewitness identifications are a cause of wrongful convictions. It’s this kind of deep dive, paired with reviews of individual cases, that could prevent future wrongful convictions and rectify present-day wrongs, he said.

Lametti insists Bill C-40 leaves flexibility for systemic reviews and that the new commission will reach out to underserved communities. As for funding, the 2023 budget proposed $83.9 million over five years for the commission, beginning in 2023-24, and $18.7 million ongoing.

The exact number of wrongful conviction cases that exist is impossible to know.

“Given that it entails measuring the unknown, no Canadian studies to date have identified an accurate proportion (of wrongful conviction cases),” Ian McLeod, a spokesperson for the federal justice department, said in a statement.

McLeod said some U.S. studies estimate wrongful convictions make up three to six per cent of criminal cases in that country. By conservative estimate, if 0.5 per cent of people sentenced to custody in Canada are wrongly convicted, that’s approximately 450 cases a year.

“I don’t think any of us can say with certainty what that number is,” Roach said.

“But I think the tougher the system is to get a remedy — either to undo the conviction and/or to get compensation — the more rational it becomes for people just to (accept their fate) and say, ‘Yes, I was wrongfully convicted and I’m going to serve my time and I’m going to try to get on with my life the best I can.’

“We just don’t know how many people are out there like that.”

What is clear is that Manitoba has become a hot spot for wrongful conviction remedies in recent years. Of the 14 cases involving 16 men referred back to the courts by the federal justice minister in the last 10 years, five Manitobans were involved in four cases.

These include the recent high-profile case of Brian Anderson, Allan Woodhouse and Clarence Woodhouse, who were convicted in the 1973 death of Winnipeg restaurant worker Ting Fong Chan.

The men always maintained their innocence, testifying that police beat them and coerced them into signing confessions.

Anderson repeatedly sought to clear his name, speaking to media about his plight, but it wasn’t until Innocence Canada came forward in recent years with an application to the federal justice minister that the matter was sent back for a new trial. Manitoba’s top judge has since declared all three men “innocent.”

A fourth man convicted alongside them, Russell Woodhouse, has since died, but Innocence Canada is also seeking an exoneration for him.

Meanwhile, the federal government’s hope is that a more accessible, proactive review commission will encourage more applicants.

Roach and others welcome steps to make the application process more accessible but are concerned the new system will be overwhelmed, as happened in New Zealand. If the commission is not properly funded and staffed, it won’t be able to keep up, he said.

The current Criminal Conviction Review Group has received approximately 220 applications since 2003. Of those, 30 have resulted in legal remedies.

McLeod said the justice department anticipates 250 applications in the first two years “based on increased awareness of the review process, the independent nature of the review body and the new two-pronged test for referral — a miscarriage of justice may have occurred and it is in the interest of justice to make a referral.”

He added that the ability to appoint up to nine full-time commissioners “is intended to provide the flexibility needed to ramp up the commission’s capacity in accordance with the actual volume of applications it receives.”

Leonetti, the New Zealand professor, is a strong proponent of better data tracking, something LaForme and Westmoreland-Traoré called for, but it remains unclear whether Bill C-40 will follow through on it.

“In an ideal world, I’d want people whose job it was just to go through the applications and code for hundreds of factors that may or may not be an active issue in a referral back to a court of appeal,” she said.

“You’d want to collect data on geography, socio-economic status … the prosecutors, on the defence lawyers, on the trial judge.”

Analysis of this data could reveal trends that have previously gone unnoticed and root out potential wrongful convictions, she said.

Substantial work on this front is being done by a group of volunteers responsible for the first Canadian Wrongful Conviction Registry, unveiled in 2023. The comprehensive website and accompanying database was compiled over five years by a team including Roach and co-founder Amanda Carling, a Métis lawyer.

The registry currently includes 89 cases of recent and historic wrongful convictions in Canada, dating as far back as the hanging of Louis Riel in 1885. Among the revelations made public through their work: just 13 of the 89 wrongful-conviction victims were women, five were Black and 18 were Indigenous.

“We like to hang our hats on the fact that … at least we’re not that bad, at least our human rights violations aren’t that bad. And I don’t know that that’s true.”–Amanda Carling

The database lists information about each case, naming the prosecutors, police and judges involved, and gives details about the victims, including socioeconomic status, occupation, age, whether they were a survivor of residential schools or racialized.

It also lists factors that contributed to the wrongful conviction, including the circumstances of the crime or so-called crime.

It reveals that false guilty pleas occurred in 16 cases — 18 per cent of all cases — and that in 32 cases, or 36 per cent, no crime actually occurred, such as instances where someone was charged with murder but the person died from natural causes.

Carling said she hopes the registry is a wake-up call to Canadians who think we don’t perpetrate injustices in the same way as other countries, such as the United States.

“We like to hang our hats on the fact that … at least we’re not that bad, at least our human rights violations aren’t that bad,” she said. “And I don’t know that that’s true.”

She said Canadians should recognize the legacy of colonialism, residential schools and anti-Black racism within the judicial system and the disproportionate impact wrongful convictions have on Black, Indigenous and racialized Canadians, even if statistics don’t reflect it yet.

While the registry is only the tip of the iceberg, Carling hopes it forces governments to accept cases are not just “one-offs” but are representative of broader issues.

“Canada needs to reckon with its own history of human rights abuses — and that’s what miscarriages of justice are,” Carling said.

The Bill C-40 commission is expected to offer one approach to addressing wrongful convictions, but legal experts point to other steps that could improve the system.

Brandon Trask, an assistant professor of law at the University of Manitoba who runs the university’s Rights Clinic, says his major concern is political influence creeping into the justice system and impacting wrongful convictions.

“When we have politicians who are quick to comment on cases or just the environment more generally — ‘Oh, we can’t have people being released on bail’ — and all these political talking points that are meant to get votes, (they) create some real liabilities in the justice system,” Trask said, noting those liabilities include keeping people behind bars or shortcuts with rules of evidence.

“All of those things come with risks.”

The worry with issues such as making it harder for someone to get bail, Trask said, is that people will decide to plead guilty, whether they committed a crime or not, simply because they will have already racked up enough time served to get out rather than facing a drawn-out trial.

“So, if we move to essentially a fast-food model for the criminal justice system, we massively increase the risk of wrongful convictions,” he said. “Cutting corners is very dangerous, as we’ve seen time and time again.”

He has similar concerns with mandatory minimum sentences, in that someone might take a plea deal and plead guilty to a lesser crime they didn’t commit rather than face an even longer sentence if the case goes to trial.

Trask fears some will view the proposed commission as a safety net, arguing that if wrongful convictions occur, they can be dealt with through the system.

“Well, no, we need to work on preventing them in the first place,” he said.

katrina.clarke@freepress.mb.ca

Katrina Clarke

Investigative reporter

Katrina Clarke is an investigative reporter with the Winnipeg Free Press.

Dan Lett

Columnist

Born and raised in and around Toronto, Dan Lett came to Winnipeg in 1986, less than a year out of journalism school with a lifelong dream to be a newspaper reporter.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.