CHERNEVE, Ukraine — To this day, Darlene Clark remembers what her father, William “Gus” Wasiuta, always said when he was feeding birds in the yard, or shooing a fly out of the house. He’d always shoo, but never swat; he couldn’t bear to take a life without a reason.

“Vse khoche zhittya,” he’d say, in Ukrainian. Everything wants to live.

Wasiuta had seen enough of both life and death to know what that desire meant.

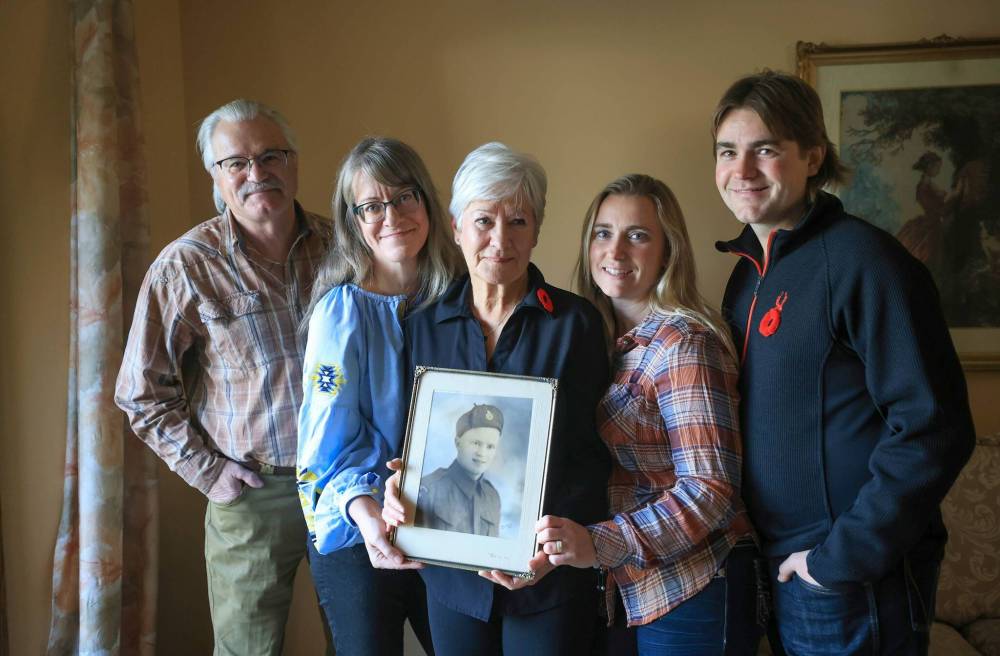

RUTH BONNEVILLE / FREE PRESS

Gus Wasiuta’s family, Steve Wasiuta (from left), Alyssa Rempel, Darlene Clark, Kylie Wasiuta, and Cole Wasiuta.

He was born in January 1923, the fourth child of a big Ukrainian family from Elma, on the shores of the pretty Whitemouth River. When he was six years old, his mother died in childbirth, leaving his father to raise six children alone.

It was a tough life, but with the help of the close-knit Ukrainian immigrant community, they got by. Wasiuta left school after Grade 9 to help on the family farm; a few years later, he travelled north to Flin Flon to work in the mines, hoping to earn money to send home.

Then the Second World War erupted in Europe, and his gaze turned across the ocean.

From the start, Wasiuta was hungry to join the fight. He was “tired of living under the ground,” he told his daughter decades later; like many young men at the time, the idea of going to war seemed a chance to not only liberate Europe from the Nazis, but also to see the world.

At just 17 years old, he enlisted in the Canadian Army. By 1943, he was stationed in Europe. The army wouldn’t send him to the front — a bad bout of frostbite as a child had left him with gnarled feet. It didn’t slow him down, though the army ruled he wasn’t fit to march.

Instead, he was assigned as a truck driver, hauling supplies across bomb-blasted Belgium, the Netherlands and France. He saw death and lost many friends. He hunkered in bunkers while warplanes shrieked overhead.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / FREE PRESS

At just 17 years old, Gus Wasiuta enlisted in the Canadian Army. By 1943, he was stationed in Europe.

But there were also moments of delight, and he wrote about them in a small pocket diary that he kept all his life. There were the kids he met in war-ravaged villages, who would squeal with glee as he handed out chocolate and hunks of bread.

“If there was anything extra he had, he’d always give it to all these little kids,” Clark says.

When Wasiuta came home from the war, the rest of his life fell neatly into place. The moment he stepped off the train in Elma, he met a young woman, Lillian, who’d come to welcome the returning soldiers. They soon married and moved to Winnipeg, where they raised two children and he built a successful career as a construction manager.

As the years turned, he never lost touch with his roots or his extended family from Ukraine. In the 1970s, his cousin Ivan moved to Winnipeg to work as a tailor; Wasiuta took him under his wing and helped him send money and gifts to his children and grandchildren in Ukraine.

To his children and grandchildren, Wasiuta spoke often about his years in the war. Only the good things, though. He talked about the friends he’d served with and the pretty girls they’d met; he was proud to wear his medals and go through photo albums from his service years.

But when Clark once asked her dad if he’d like to visit a Royal Canadian Legion to spend time with other Second World War veterans, he declined.

“All of us who came back saw things that we will never forget,” he told her. He didn’t want to sit and talk about those things anymore.

Above all, Clark says, he was always grateful for the life he’d survived to see, which so many of his friends had not. He declared his goal to make it to a triple-digit age, and almost succeeded.

He died in June 2021, at 98 years old.

RUTH BONNEVILLE / FREE PRESS

Gus Wasiuta was proud to wear his medals and go through photo albums from his service years.

Eight months later, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

“Honestly, I remember thinking, ‘It’s a good thing he’s not here to see this,’ because I think he would just be heartbroken to see this happen again,” Clark says. “He was a very hopeful man, and a very positive man. But this would be very hard for him.”

She watched the news in horror. In the years before her father died, her side of the family had reconnected with Wasiuta’s extended relatives in Ukraine. Through social media, they got to know the family his cousin Ivan had supported while he was working in Winnipeg.

So Clark knew that one of Ivan’s grandsons, Vasyl Vasyuta, was serving in the Ukrainian army, along with three of his sons. She feared for them — especially the youngest, Dmytro, who was just 20 years old, an unusually young soldier in a war largely fought by the middle-aged.

In some ways, Dmytro Vasyuta was very much like Clark’s father. They bore the same last name, though transliterated in a different spelling. They were both gregarious boys from big families, who grew up working hard in tight-knit Ukrainian-speaking villages.

They even looked similar, though this may just be a coincidence, separated as they were by time and distance. Still, in photos of young Wasiuta from his service in the Canadian Army, and of Dmytro at nearly the same age, they bear the same broad jaw, the same mouth, the same wide bright eyes.

Above all, they were both just teenagers when they stood up to fight in the biggest war of their generations. But one’s life was long, the other far too short. One got to go home when his war was over and raise his children in the relative comfort of an enduring peace.

The other never came home again. And on Remembrance Day, as Canada pauses to honour those who served, Clark will go to pay her respects at her father’s grave — all too aware that, for his family on the other side of the ocean, the fight is still going on.

As a boy, Vasyl Vasyuta heard about his family in Canada. He knew about his grandfather Ivan, who he’d never met, but who lived in Winnipeg and sent parcels home to Ukraine — usually a bit of money and prized shawls for the women.

Those bonds held strong, despite distance. When his brother and some of his children began getting to know the Winnipeg side of the family, including Darlene Clark, it seemed natural that they should keep those connections alive.

“In Ukraine, probably everyone is so close to each other,” says Vasyl’s wife Halyna, speaking through a translator at their home in Cherneve, a cosy village on Ukraine’s western edge.

MELISSA MARTIN / FREE PRESS

At Vasyl and Halyna Vasyuta’s home in Cherneve, Ukraine, a memorial for their son Dmytro, who was just 20 years old when he was killed early in the full-scale invasion. Four members of the Vasyuta family have served in the current war.

It’s an unseasonably warm day in early November. At the family table, Vasyl pops the cork on a bottle of sparkling wine as Halyna lays out a lunch of soup and pyrih z kartopli, a hearty potato pie. Outside, a scruffy dog named Ryzyk frolics in the yard; it was Dmytro’s, Vasyl explains. He rescued it when he was in the army.

Against the wall, a framed photo of Dmytro sits surrounded by fresh white-and-yellow flowers.

“It’s been three years, but we don’t feel the time,” Halyna says, gazing at the portrait of her son. “For a long time, I could not stay alone in the house. I was waiting for him to come here and open the door.”

Once, Dmytro’s personality filled this house. He was born in the middle of the Vasyutas’ nine children, and grew into an active, friendly boy. He was a natural leader, Halyna says. He loved playing soccer and working odd jobs for pocket change, and had a big group of friends from the neighbouring villages.

He was not, she admits, the best student. But he loved history classes, and through learning history, came to love Ukraine. Shortly after graduating from high school in 2019, he announced he wanted to join the army.

Halyna was surprised — he was too young, she thought. But Dmytro was determined.

“He was very motivated,” Halyna says. “He was very patriotic.”

That November, just two weeks after his 18th birthday, he went to enlist in the military.

SUPPLIED

While Dmytro Vasyuta was serving in southern and eastern Ukraine, he rescued a dog, Ryzyk. After Dmytro was killed in February 2022, Ryzyk came to live with his parents in their village of Cherneve.

He did not go alone. That day, Vasyl went with him. The elder Vasyuta had first signed up for the army in 2015, shortly after Russian-backed separatists seized much of Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region. It seemed the patriotic thing to do, Vasyl says, to protect their home.

For the next several years, he held the line in the separatist war. Two of his older sons had also enlisted. Now, with Dmytro eager to join the military, Vasyl decided he would also serve another stint, hoping that, this time, the long-simmering war would finally be finished.

From the beginning, army life suited Dmytro well. When he had a break from his unit, he came back to talk to Cherneve school kids about his experience. He loved to use his small wages to help his family; he’d take his younger siblings shopping, and tell them to buy whatever they wanted. He planned birthday surprises for his mother.

“He always took care of me,” Halyna says. “He was a good boy.”

Then came Feb. 24, 2022. The day Russia invaded, and the Vasyutas’ lives changed forever.

At home in Cherneve, Halyna prayed fervently for her husband and sons, stationed in different parts of Ukraine. Dmytro’s unit was positioned in the southern city of Mykolaiv, right in the path of the Russian army’s push north. For the first few days, he called his mother to reassure her.

“He said, ‘Mom, everything is all right with me, I’ll call you later,’” she says.

But the next call never came.

MELISSA MARTIN / FREE PRESS

Vasyl Vasyuta stands beside his son Dmytro’s grave in their village of Cherneve, in Western Ukraine. Just 20 years old, Dmytro was one of the first soldiers from the Lviv region to die in combat during the full-scale invasion, and one of the youngest.

On Feb. 27, just three days into the full-scale war, Dmytro was killed as his unit fought to free other Ukrainian soldiers from an encirclement. He was one of the first soldiers from his region to fall in the broader conflict and, at the time, he was also the youngest.

Grief swept through Cherneve. Ukrainian media and even a German reporter came to cover his funeral. Hundreds of residents from the Lviv region came to mourn him, lining the narrow roads of the village for the procession, falling to one knee as his casket passed.

In Winnipeg, Clark and her daughter watched Dmytro’s funeral live-streamed online, brought to awed tears by the magnitude of the communal grief.

“I’m probably of that generation where I thought myself and my immediate family would not see another war,” Clark says. “So to have a family connection, and with the technology now being able to talk to them… it’s way closer than seeing it on the news. It’s very hard.”

Today, flags of Ukraine and the 80th Brigade flutter over Dmytro’s grave, an elaborate tomb of grey stone engraved with the white tryzub symbol of Ukraine. Nearby, there are graves of four other soldiers from the village, including a classmate of one of the Vasyutas’ older sons.

After Dmytro died, a local politician promised to name a street after him. But then so many more lost their lives, Vasyl says, that “maybe they changed their opinion.” An entire generation has been lost, he says: of the 75 soldiers Vasyl first served with in 2015, only nine are still alive.

This is the cost of the fight for independence, and for Ukraine, as it was across Europe more than 80 years before, it is unbearably heavy.

And it’s not over, not even for the Vasyuta family. Vasyl kept fighting until he was injured. Another son was injured, but survived and retired from service. Eldest son Maryan is still holding the line near Toretsk, along the brutal Donetsk front.

MELISSA MARTIN / FREE PRESS

Vasyl Vasyuta, 53, shows some of his service awards at his home in Cherneve, in Western Ukraine. Vasyl served in the Ukrainian army since 2015 and fought in some of the toughest battles of the full-scale invasion, until he was injured last year.

When Vasyl thinks about Dmytro’s sacrifice now, he is quiet for a moment, his jaw trembles. He’s proud of his son — he did a good job, he says. He stood up for his country, and what he believed. But so many Ukrainians have given so much, and the loss runs so deep.

“We’re afraid that this sacrifice, this price will be for nothing,” Vasyl says. “If we will sign some peaceful negotiations with Putin, a lot of people will recognize that all of these deaths were for nothing. People will not accept it. There will be some kind of revolution.”

Which brings us to one last question. This heavy cost, this grief — what makes it worth it? What, in other words, makes Ukraine worth fighting for?

Vasyl gives a simple answer.

“If the Russians come here for a third time, they will kill us,” he says. “You know, someone once joked that the Russians were better from 1939 to 1941 — they came and they left. The second wave of Russians was worse; they came in 1945 and left in 1991. If the third wave comes, we will be killed.”

These are “very dark days,” he adds. “But life is going on.”

Vse khoche zhittya. Everything wants to live.

Melissa Martin is the Free Press’s writer-at-large. She is currently on leave in Ukraine.

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large (currently on leave)

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.