There isn’t much Justin Lamoureux doesn’t know about knives.

The bladesmith has always been interested in the craft, his interest piqued after observing a blacksmith at work during childhood visits to Festival du Voyageur.

The Creators

The Creators is a series that examines the aha moment behind ideas, images and inspiration, and the people behind them. See more in the series.

Bladesmithing as a career seemed very much out of reach — until Lamoureux started watching the competitive bladesmithing TV show Forged in Fire.

It gave him the impetus to pursue his passion.

“The series removed some barriers for me because I could see how other people were doing it,” he says. “It led me to think I could do it myself. It made me do research to see what I needed to learn to take on the craft.”

Justin Lamoureux is the current president of the Manitoba Blacksmith Guild and is also featured in a streaming TV show, Fire & Slice, which documents the process involved in crafting his custom knives. (Ruth Bonneville / Free Press)

Lamoureux has come a long way since he started out eight years ago.

He is president of the Manitoba Blacksmith Guild; he’s just created and run his first craft market, Cedar & Steel; and he also has his own show, Fire & Slice on the Bell MTS Fibe TV streaming service, which documents the construction of his custom knives.

Making a custom knife can take anywhere from 15 to 80 hours.

Lamoureux’s blades are made from either high-end stainless or carbon steel. The latter requires more maintenance.

“Function also dictates a lot. Is it for the kitchen or for the field? Culinary knives are harder to make as they demand more precision. A culinary knife has a lot more nuance than something you are going to use to carve a stick or chop down branches,” he explains.

But he relishes the challenge. He sees himself crafting a full set of custom culinary knives one day.

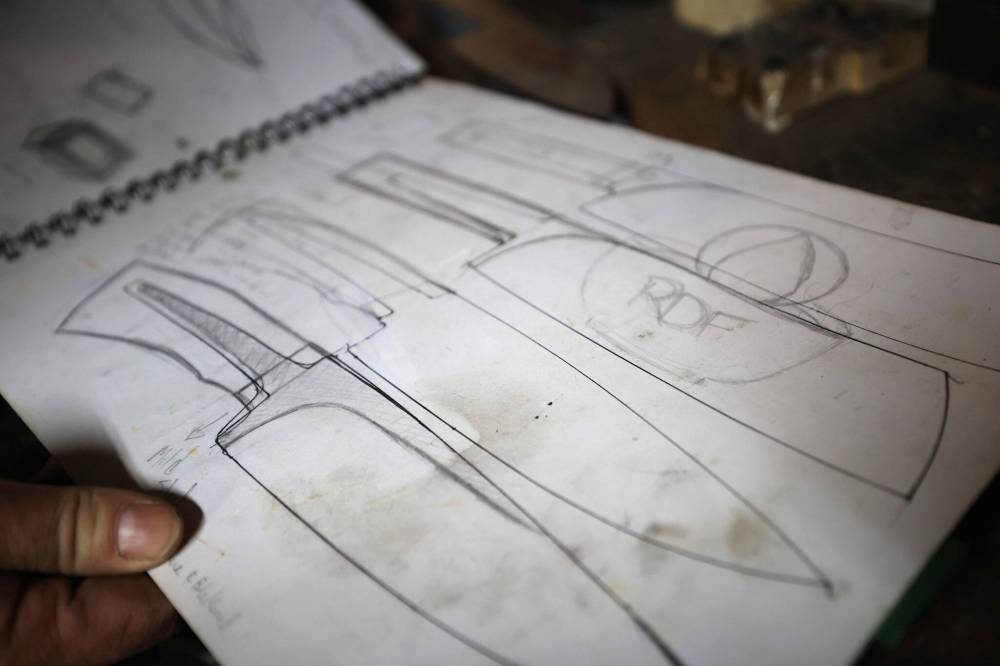

Photo of drawings and plans for each blade. (Ruth Bonneville / Free Press)

“Custom knives tend to work a lot better than what you would find in a retail environment. Retail store knives have much softer blades. They are made to be good enough to cut with but they don’t retain their edge for as long,” he says.

But whatever the steel — stainless or carbon — never use glass or stone cutting boards during kitchen prep, he warns.

Justin Lamoureux started pursuing his dream of becoming a bladesmith eight years ago. (Ruth Bonneville / Free Press)

Small hiking knives (Ruth Bonneville / Free Press)

“It will dull your knife quickly. People should use a wood cutting board and oil or wax it regularly. Quality knives should never go through a dishwasher. Use it, wash with soap and water, and then wipe dry. This is doubly important with carbon steels. Oiling the blade from time to time is recommended, too.”

Sharpening knives incorrectly can bring about even more damage. Lamoureux says natural sharpening stones are best, especially when honing a custom knife. Pull-through sharpeners should be avoided at all costs.

His knives are made in one of two ways: stock removal or traditional forging with hammer and anvil.

Working from his home shop in St Norbert, Justin Lamoureux starts the day by lighting his forge before picking up his hammer and anvil, ready to shape sheets of steel into daggers, cleavers and bowies. (Ruth Bonneville / Free Press)

Stock removal is the most efficient — and advantageous — method of knife making. It requires less processing, as sheets of metal arrive annealed and ready for heat treatment. Lamoureux draws the shape of the blade on the steel before he sends it to be water-jetted, a method where a mixture of abrasives and high-pressure water stream are used to cut precise blades.

Forging a knife the traditional way subjects the steel to molecular transformations, resulting in metal that is less effective. The steel loses its toughness, becoming more prone to breakage.

Hand forging, however, retains the artistry of the craft.

“Physically working on the steel with a hammer and anvil allows for far more creativity,” he says.

An experienced bladesmith like Lamoureux can weave textures into the steel, or laminate different steels to create a blade composed of a number of steels — each with its own contraction rates and unique qualities — welded together to make one whole piece.

Lamoureux is currently working on a blade to be given as a gift to a member of the military about to go on their first overseas posting. As well as crafting new knives, he is also able to recreate knives from photographs. He also takes on knife repairs.

He posts new works on his Rainy Day Forge website and to his Instagram account.

av.kitching@freepress.mb.ca

AV Kitching

Reporter

AV Kitching is an arts and life writer at the Free Press. She has been a journalist for more than two decades and has worked across three continents writing about people, travel, food, and fashion. Read more about AV.

Every piece of reporting AV produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.