A voice for Japanese Canadians and a leading figure in Japanese-Canadian culture, Grace Eiko Thomson was a mother, grandmother and great-grandmother with an unstoppable commitment to justice that continued until the very end of her 90 years.

Her painful early life experiences became the catalyst for transforming outrage into action.

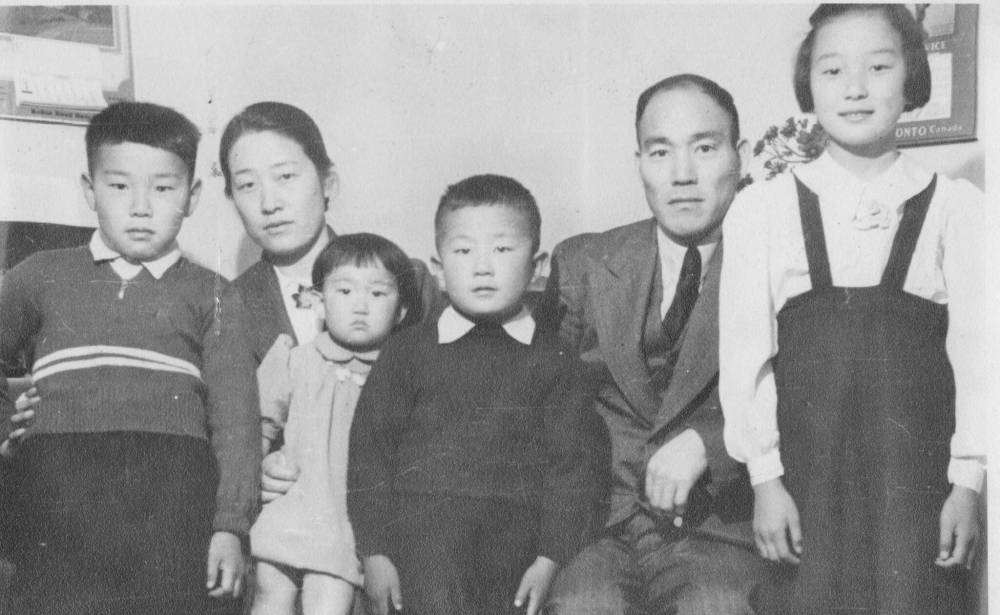

Born in Steveston, B.C., Thomson was the second oldest of five children born to Torasaburo Nishikihama and Sawae Yamamoto, who had emigrated to Canada from Japan and settled in Vancouver.

Supplied

The Nishikihamas, from left: Tom, mother Sawae, Keiko, Kenji, father Torasaburo and Grace.

When she was eight years old, everything was turned upside down. In 1942, the Order in Council under the War Measures’ Act authorized the removal of all persons of Japanese racial origin from the restricted zone on the West Coast.

The Nishikihamas lost their livelihood, had their property confiscated and were transported to an internment camp at the Minto mine in the B.C. interior, where they were forced to remain until 1945. Although they were Canadian citizens, the law prohibited them from living west of the Rockies until after 1949, coinciding with the return of their voting rights.

Unable to return to the coast, the Nishikihamas moved to Manitoba, arriving first in Middlechurch — where they lived in a barn — then in Whitemouth, before settling in Winnipeg in 1950.

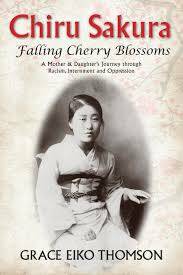

The historian, teacher and writer dedicated her life to bringing attention to this dark period in Canada’s history. Thomson documented the stories of identity, trauma and racism and her efforts to find social justice, for herself and others, in her 2021 memoir Chiru Sakura: Falling Cherry Blossoms, shortlisted for the City of Vancouver Book Award.

Thomson died on July 11, 2024, at home in Winnipeg. Though she had lived in Vancouver since 1995, in 2023 she moved back to Winnipeg to be close to her family.

In a tribute at the memorial, Thomson’s younger sister, Keiko Miki, remembered living on Isabel Street and Logan Avenue, when her sister biked to St. John’s High over the Salter Bridge, returning home to start dinner, as both parents worked.

“Grace was forced to take on responsibilities beyond her years, babysitting, making meals, interpreting. She mentioned to me more than once that she had carried me, as a baby, strapped on her back. She often spoke about her lost childhood with regret and a sense of rage at what had happened.

Supplied

Thomson, age 15, with sister Keiko in Whitemouth.

“Through hard work and determination, she powered through to fight discrimination, misogynies, narrowmindedness and criticism along the way. She was resilient. She used her own experiences to teach others it was OK to speak up.”

Soon after arriving in Winnipeg in 1950, Thomson left school and found office work to help support her family, quickly becoming a valued personal secretary and administrative assistant in business and law.

She married Alistair Thomson in 1959 and had two sons, David and Michael.

In the ’70s, Thomson continued her education and attended university as a mature student, receiving a BFA Honours in 1977 and a master’s degree in Social History of Art from the University of Leeds, U.K., in 1991.

Thus began her career as a teacher, curator, adviser and writer — at the University of Manitoba, the Burnaby Art Gallery, the Sanavik Inuit Cooperative in Nunavut and as inaugural curator and director of the Japanese Canadian National Museum. Thomson was especially proud of the exhibition Leveling the Playing Field: Legacy of Vancouver’s Asahi Baseball Team and her role in developing the Japanese-Canadian gallery at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

Thomson served the wider community in a variety of capacities for numerous organizations and as an activist and advocate for justice.

“She had a lot of impact with the younger generations and the arts community, they looked up to her as a mentor for her wisdom,” said brother-in-law Art Miki.

Supplied

Grace Eiko Thomson believed she had an obligation to stand up against injustice in the Japanese-Canadian community and beyond.

“That was really noticeable when she passed away. All these young people were indicating how much they appreciated her help and mentorship.

“Grace was really a strong person in the sense that she really believed in the history of our community. She was quite involved with the Indigenous community in B.C. She was given an honorary elder (designation) and she was very proud of that.”

“Grace marched with Indigenous peoples in reconciliation marches in Vancouver and participated in their sharing circles,” said Shelley Joseph, the daughter of Chief Robert Joseph, the ambassador for Reconciliation Canada and the Indian Residential School Survivors Society.

“Personally, she was an influence to me. I admired and modelled how passionately she showed up in all spaces that we shared and all people we had dialogue with. My most cherished memory was spending a whole day with her as we supported the Jewish community on Yom Hashoah. We stuck to each other the whole way to Victoria and back,” said the facilitator and cultural knowledge keeper.

Thomson believed passionately in the work being done to increase awareness of the impacts of intolerance and racism and shared a vision of reconciliation and healing.

“She was very much shaped by her childhood trauma and her experience as a visible minority growing up in the 1950s,” said her son, Michael Thomson. “She was driven to succeed and worked incredibly hard. She was always moved to act, to intervene where she thought that things were happening that weren’t right.

“She was uncompromising about most everything, highly principled and demanding as a parent but I respect that and understand where that came from. Each of us has an obligation, and I know that sounds cliché, to stand up and for principles, for each other, to stand up against any injustice or unfairness that exists. That’s her, her whole life was trying to do that.

In her 2021 memoir, Thomson documented the stories of identity, trauma and racism and her efforts to find social justice for herself and others.

“Initially, for her family as a kid, for her community later — and then that became the downtown East Side; it became the Indigenous community in B.C., the arts community — until the final day,” he said, noting that even as he cleaned up her books, papers and documents after her death, it was clear that she was still writing and actively involved in advocacy.

“That’s the driven part. Her expectations were always high,” he said, noting that her drive also included maintaining a healthy rapport with his father even after the marriage ended when he was in his teens.

“They continued to be supportive and respectful of us and each other. They were always together at family events, neither re-partnered. They prioritized their kids.

“My mother belonged not just to us but to the Japanese-Canadian community and to the larger community. There’s much more about what she did in the world, not just meaningful for her but meaningful for us as well. That’s the story. That’s what she was about.”