The National Hockey League announced Friday that Rick Bowness is one of the three finalists for the Jack Adams Award, which goes to the coach of the year.

It’s the first time Bowness has been up for the award and a fitting honour for the Winnipeg Jets bench boss, who announced his retirement three days later, after 2,726 NHL games as a head coach and assistant for eight franchises over 38 seasons and five decades.

I don’t have to wait for the NHL awards on June 27 to know who wins, though.

It’s been well documented what “Bones” did since being hired by the Winnipeg Jets two seasons ago and how he changed the culture of the team.

Bowness intervened in what had been described as a toxic locker room. He rebuilt the team’s identity and fostered an atmosphere of accountability and interdependence. He empowered a team that finished fourth overall and had the best defensive stats in the league.

I could go on, but I’d rather let my sports colleagues do that.

When I recall the 2023-24 season, though, I won’t remember any of that.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS FILES

Jets head coach Rick Bowness is one of the three finalists for the Jack Adams Award.

I’ll remember this.

As in the past six seasons, True North Sports and Entertainment held its annual WASAC Winnipeg Jets game in February honouring First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities. Partnering with the Winnipeg Aboriginal Sport Achievement Centre, the evening puts the spotlight on Indigenous cultures, leaders and contributions.

This year my father Murray and daughter Sarah were recognized at centre ice in the ceremonial puck drop alongside other accomplished Indigenous athletes, elders and leaders.

Dad is, of course, Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge, the former head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and a former Canadian senator. Sarah is an activist, a musician and an emerging public speaker and leader in her own right.

It was a beautiful moment for my family, highlighted by the standing ovation the sold-out crowd gave to my father when he walked onto the ice.

Dad is getting older and it’s increasingly difficult for him to appear publicly. He has spent a lifetime loving his home and witnessing it love him back was, in a word, emotional.

“Sir, have you got a moment?”–Rick Bowness

This story, though, begins when he and my daughter came off the ice.

At Canada Life Centre, people who make their way to centre ice have to walk through the home team bench gate via a small, cramped hallway under the stands.

There’s not a lot of room and security keeps people moving through the area quickly. According to league rules, no one else is really allowed to get near the ice. Even Manitoba Premier Wab Kinew, who was there to offer greetings, wasn’t permitted to get close.

When Dad and Sarah finished the ceremony and made their way back through the gate at the Jets’ bench, they were quickly whisked away down the hallway to the spot where I was waiting for them.

According to NHL rules, a small amount of time is allotted after the ceremony — about 90 seconds — for TV commercials before the game begins.

So, as the three of us were being rushed away, I saw a man in a suit walking quickly down the hallway.

“Sir, have you got a moment?”

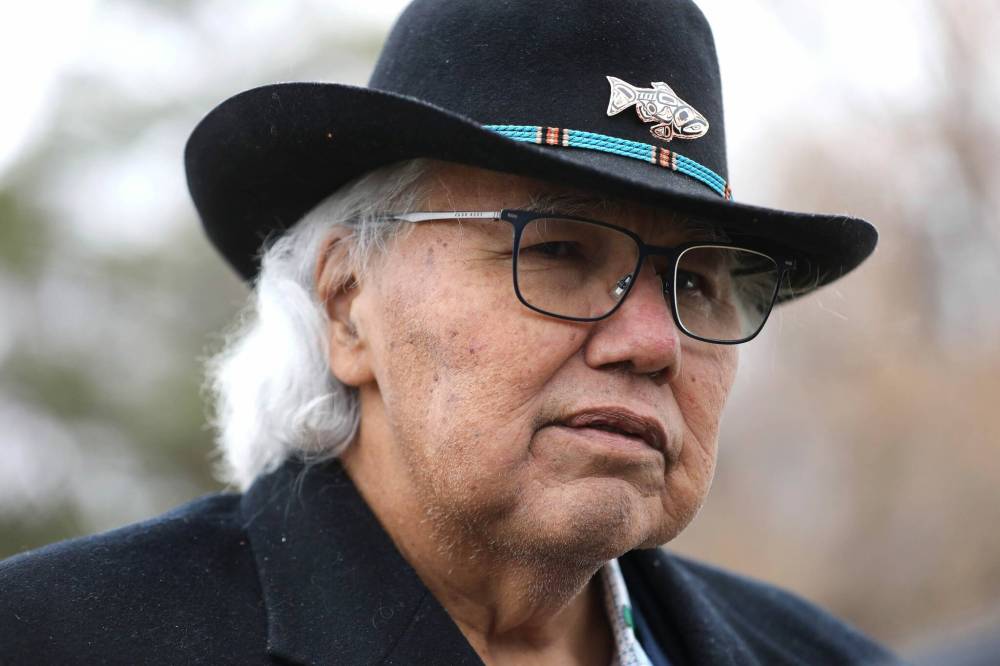

RUTH BONNEVILLE / FREE PRESS FILES

Murray Sinclair was recognized at centre ice in the ceremonial puck drop alongside other accomplished Indigenous athletes, elders and leaders at the Winnipeg Jets annual WASAC game in February.

It was Rick Bowness, offering his hand.

My father turned and, seeing who it was, held out his hand.

“Sir, I want to tell you how much you mean to me and to all of us,” Bowness told him. “What you have done for this community and this country is incredible. I thank you.”

The two men then stood together and talked. The crowd above us started to cheer so I couldn’t hear what was being said. I remember, though, how they both laughed at something and Bowness put his other hand on my father’s shoulder.

They had never met before, but the warm exchange suggested they were old friends.

I admit to feeling a bit star-struck. I remember when Bowness became the coach of the original edition of the Jets in 1988, when I was a hockey playing 12-year-old.

Miigwech, Bones

Someone called out from down the hallway.

“Coach, we started!”

Bowness apologized, said hello to me and my daughter, and rushed back down the hallway to take his spot behind the bench.

The NHL season was frustrating for various reasons. I particularly hated how the league took a big step backwards with Indigenous communities — banning the presence of Indigenous-artist created jerseys, helmets and logos in pre-game ceremonies while continuing to allow divisive, racist and stereotypical images throughout games.

It’s almost as if the NHL forgot whose lands their teams play on and the relationships every single franchise, arena and fan shares with the first peoples of this place and so, what happens to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples happens to all.

I know one coach, though, who didn’t forget. He made it a part of his job.

Miigwech, Bones. Even if it was just for a little while, you gave us all a lot.

You’re my coach of the year.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair

Columnist

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.