An estimated 30,500 Canadian women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in 2024. Approximately 5,500 will die from the disease.

On average, 84 Canadian women are expected to be diagnosed with breast cancer each day this year; 15 per day will die from it.

One in eight Canadian women will develop breast cancer during their lifetime. The disease will claim the lives of one in 36 women. Your mother, sister, wife, daughter, cousin, aunt, friend.

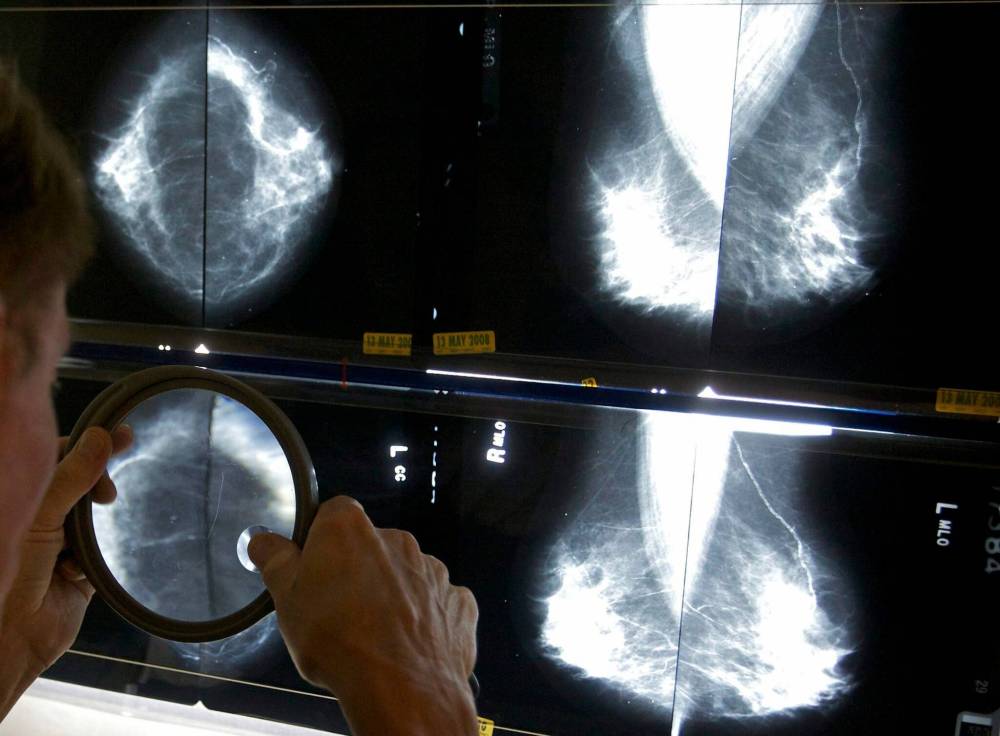

A radiologist uses a magnifying glass to check mammograms for breast cancer. (Damian Dovarganes / The Associated Press files)

The statistics are sobering.

Breast cancer is the most common form of cancer among Canadian women, with the exception of non-melanoma skin cancers, according to the Canadian Cancer Society. It is the second leading cause of death from cancer in Canadian women.

Like most forms of cancer, early detection is the key to improving outcomes from the disease. That is why most provinces in Canada have either lowered the age for routine breast cancer screening from 50 to 40 or are in the process of doing so.

Manitoba is one of the few exceptions.

The Canadian Cancer Society recently urged all provinces and territories to lower the age for mammograms to 40, citing emerging scientific evidence that shows it reduces the risk of death in women in that age group. About 13 per cent of breast cancer cases occur in women between the ages of 40 and 49.

“There’s strong enough evidence from trials, from modelling studies and from real-world data to warrant that shift to 40,” Sandra Krueckl, the cancer society’s executive vice-president of mission, information and support services, said in an interview earlier this month.

“We have been hearing for a long time now that there’s concern about (women) age 40 to 49 and their ability to access (screening).”

So why isn’t Manitoba following the lead of most other provinces on this life-saving move?

That’s a question that came up at the Manitoba legislature Wednesday as the Opposition Tories asked Health Minister Uzoma Asagwara why Manitoba is not following the advice of the Canadian Cancer Society and doing what most other provinces are doing.

The response was underwhelming.

While the province is “actively exploring” the possibility of lowering the age, government is concerned that if it does so, it may not have the resources, such as technicians, to meet the demand, said Asagwara.

“When you increase access (to breast screening), in some cases we actually see folks who need this care at older stages who are very sick not being able to access that care because of capacity challenges,” the health minister said.

“In Manitoba we are going to take a responsible, thought-out and informed approach to make sure that women not only get access to this care but we have a comprehensive strategy that meets the needs across various demographics of all backgrounds and all communities.”

So what is the plan to hire more technicians and find the resources necessary to expand this life-saving technology? There isn’t one. Asagwara would only say they’re still studying the issue.

There is nothing more to study. The evidence in Canada and the United States (where it was recently recommended that the screening age be dropped to 40, a move strongly supported by leading medical institutions, including the Mayo Clinic) is overwhelming. Reducing the screening age to 40 will detect early signs of cancer in women and will save lives. Full stop.

If there are “capacity challenges” in Manitoba’s health-care system preventing that expansion, what are those barriers, specifically, and what is government doing to address them? How many more technicians are required? The NDP government is silent on that.

In Newfoundland, where that province recently dropped the screening age to 40, health officials estimate that an additional 34,000 women will have access to mammograms. Newfoundland found a way to ensure it has the capacity to meet that demand. Why not Manitoba?

This is about life and death. Early detection of cancer is critical to improving outcomes. Governments should be doing everything possible to ensure people have the best access possible to regular screening. For women, routine breast screening between the ages of 40 and 74 is one of the most important ways to catch cancer early and reduce deaths.

If there are capacity issues preventing that from happening, government should move quickly to address them. Women’s lives are depending on it.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom Brodbeck

Columnist

Tom Brodbeck is a columnist with the Free Press and has over 30 years experience in print media. He joined the Free Press in 2019. Born and raised in Montreal, Tom graduated from the University of Manitoba in 1993 with a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and commerce. Read more about Tom.

Tom provides commentary and analysis on political and related issues at the municipal, provincial and federal level. His columns are built on research and coverage of local events. The Free Press’s editing team reviews Tom’s columns before they are posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press’s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.