Make the drive from Winnipeg to the Pembina Valley and radio goes on its own little adventure.

Not that far south on Highway 3, the jazz on 98.3 CBC and the protest punk on 95.9 CKUW become, like much of the FM band, staticky. Switch to AM, and you’ll find one of its best known art forms: conservative talk radio. Clipped voices with clever zingers about a “woke” curriculum distorting the public school system. Gentle voices unpacking the case for biblical creationism.

In an era of political polarization in Canada — which is “far and widening,” according to a 2023 report from the Public Policy Forum — you don’t want to exaggerate what separates city and country in Manitoba beyond geography. But, for visitors to areas like the federal riding of Portage-Lisgar, these are the first small reminders of how politically eclectic the province can be.

The voting district runs down the province’s centre, roughly from Lake Manitoba through the Pembina Valley to the U.S. border. Among the valley’s biggest communities are Altona, Morden and Winkler.

Painted with wheat and canola fields, lush greenery and winding creeks, the area is known for its close-knit, neighbourly communities, where evangelical and Mennonite Christianity are vital forces. The region sees a steady flow of immigrants from countries like Ukraine, the Philippines, India, Nigeria and Mexico.

“The community has grown in depth and obviously in scope,” says Martin Harder, who served as Winkler’s mayor for four terms until he stepped down in 2022. “(They’ve) contributed extremely well to the financial base that we have in Winkler, and our business base and employee base.”

The Pembina Valley is also notable for its strong, diversified economies, kept humming by agriculture, manufacturing and tourism. In the summer, visitors are drawn by its corn, apple, sunflower and harvest festivals. In the winter, parks are transformed into choice spots for cross-country skiing and snowshoeing. Winnipeggers also descend to the valley for the winter markets. And if you were driving on Highway 3 through the Pembina Valley in the winter of 2022, you might have encountered the slow-rolling vehicles showing solidarity for Canada’s “Freedom Convoy” protest.

“(The riding) is, arguably, the most right-of-conservative corner of Canada,” Canadian Mennonite magazine editor and Rural Municipality of Stanley resident Will Braun wrote last year in the Free Press. (The RM surrounds the communities of Winkler and Morden.)

“The COVID-19 vaccination rate here maxed out at 23 per cent, lower than any other jurisdiction in Canada.”

At first blush, the region seems like a compelling case study for Canada’s new “populism.”

It’s a term that has become one of the more fashionable — and contested — of recent history in North America and Europe.

It’s now commonly used to describe conservative currents in Canadian politics that have strong rural and western Canadian roots. Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential election south of the border in November is turning up the heat on Canada’s populist debate, and has some asking once again, “Could it happen here?”

This alarm is predictable. But what does populism mean, and is it really a good framework for making sense of Prairie politics?

For its boosters, populism is a grassroots revolt that fights for ordinary people’s basic rights and a chance to be heard against a corrupt elite.

For its detractors, it’s an illiberal style of politics on the left or right that stirs up tribalism based on culture or class.

Then there are those who see the term as misleading — a label ignoring the fact democratic politics have always involved coalitions built by scrappy appeals to common social identities, like rural or urban, western or eastern Canadian, working or professional class.

What’s certain is that a populist spectre now haunts Canadian political commentary. Check out the National Post, Economist, Hill Times, Globe and Mail, Vox, CBC, as well as scholarly publications, and the term is used to describe figures like convoy protesters, premiers like Alberta’s Danielle Smith and Saskatchewan’s Scott Moe, and federal party leaders such as the Calgary-bred Conservative Party of Canada’s Pierre Poilievre and People’s Party of Canada (PPC) head Maxime Bernier.

Poilievre, favoured to win the next federal election, polls highest on the Prairies: as of Nov. 18, he claimed 58 per cent support in Alberta and over 50 per cent in both Saskatchewan and Manitoba. In the past month alone, this figure has increased in Manitoba, and a full 68 per cent of men in the province ages 18-35 now support the Conservative leader, according to a recent Free Press/Probe poll.

There’s a contender even further to the political right who also treats the Prairies as a stomping ground. That’s Bernier, who recently staked the future of the PPC in Portage-Lisgar, even though he doesn’t live in southern Manitoba.

Bernier — who was arrested in 2021 for violating public health orders at an anti-lockdown gathering in St. Pierre-Jolys, wants the Multiculturalism Act repealed, and told a Manitoba gathering in 2023 society had been “overtaken by evil” and “pervert ideas” — ran in the district’s 2023 byelection.

Bernier’s influence shouldn’t be exaggerated in the region. For all the online images of him giving the thumbs up and hugs to Manitobans, he came a distant second in the byelection against Conservative candidate Branden Leslie, though he vows to run again in the riding.

The byelection result may seem like a decisive rebuke of Bernier and his anti-multiculturalist politics in favour of Poilievre’s clear efforts to build a multi-ethnic coalition while nevertheless supporting hard immigration caps.

Still, there were a handful of polling stations where Bernier outperformed Leslie. Most are clustered near the U.S. border in neighbouring communities like Winkler, Rhineland, Blumenfeld and Schanzenfeld. This border proximity is a reminder of ongoing debates about the extent to which rising “populism” in Canada should be seen as an American import, echoing the patriot movement, the American Christian right and, of course, Trumpism and the MAGA movement broadly.

But rural southern Manitoba has its own uniquely regional traditions and political characters. And this factor shouldn’t be overlooked while reflecting on Manitoba’s political culture against larger backdrops, such as the rise of global populism or national polarization.

You can catch modern twists on Prairie tradition just by walking in downtown Winkler. Head east on Mountain Avenue, and just past the city’s mosque (approved unanimously by Winkler’s city council in 2017), and you’ll see Access Credit Union. Thousands of people in the area bank here. Then, turn right on Main Street, and a moment later you’ll see the Gardenland Co-op (part of the Federated Co-operatives Limited), a popular spot to buy groceries.

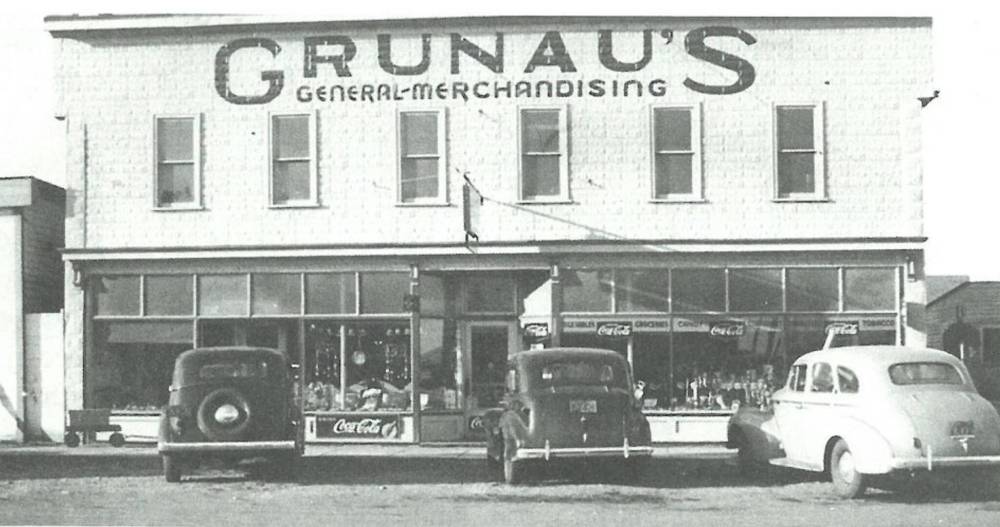

Both the modern Access Credit Union and FCL are amalgamations of many of the independent co-ops and credit unions that were once scattered across southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan. These types of organizations took off in rural communities during and following the Great Depression. They served similar needs: a way of pooling resources and creating regional self-sufficiency against a host of outside pressures.

“In a lot of cases, co-ops began to provide goods and services where there were none, and in other cases as a way to keep the profits that out-of-town businesses were taking out of their smaller communities,” says Evan Toews, Gardenland Co-op’s general manager.

“The importance of Co-op today is much the same. And also, you know, right from the start, our co-op is hugely involved locally through community support,” he says. “From events that are going on, the Co-op is involved and continues to give back through donations and by sharing our profits with our members. Community support is one of our key foundations.”

In his book Living between Worlds: A History of Winkler, University of Winnipeg historian Hans Werner notes that the same people tended to appear at early meetings of the town’s co-op and credit union. People like Winkler’s legendary political maverick Jacob M. Froese.

But these two movements sometimes found natural allies in different parts of society.

“Some Mennonites, particularly those who had experienced communism in Russia, saw the co-operative movement as an early step on the way to that system,” writes Werner.

Meanwhile, businesspeople could be wary of the co-operatives, seeing them as potential competitors for entrepreneurs like themselves.

But “the credit union,” Werner adds, “had less opposition from businesspeople because it did not compete directly with them and had the potential of relieving their burden of customer credit.”

University of Winnipeg professor and Plett Foundation executive director Aileen Friesen, who specializes in Mennonite history and migration, emphasizes the enduring power of the communist experience — and, just as importantly, the way it’s popularly remembered — in shaping Pembina Valley politics.

“Mistrust of governments justified through narratives of historical persecution and vaccine hesitancy (some accurate, many inaccurate) were by far the greater factors identified as shaping responses to COVID among Mennonites,” she says in an email.

“As a historian, it was fascinating to witness how Mennonite communities, government officials, medical experts and the media deployed Mennonite history during that period.”

She describes other cultural factors that also guide the region’s politics.

“There’s all sorts of different ideas that are fusing together. It has to do with partially the history of the region, partially the Anabaptist (culture),” she says, highlighting other influences like evangelicalism, social media and the diverse impacts of modern individualism.

Attend Winkler’s annual Christmas market, and you’ll see a few signs of the city’s complex evolution. There are youths dressed like hipsters, and others in plain dresses and bonnets. Alongside the expected mix of baked goods, artisan soaps and toys for sale, there are more exotic things like a pop-up tattoo parlour and New Age sellers peddling essential oils.

I strike up a casual conversation with one friendly vendor.

“You’re from Winnipeg, aren’t you?” she asks, and seems eager to talk politics. Before long, I’m learning about her mistrust of drug companies and elite banking interests, and her admiration for Indigenous spirituality. For all the region’s changes, she tells me Winkler remains a conservative community, “rooted in faith.”

University of Winnipeg historian Christopher Adams, author of the book Politics in Manitoba, says it’s not just culture and religion, but also material factors that help to explain southern Manitoba’s right-wing leanings.

“You look at south Manitoba, and those are rich farmlands,” he says. “They’re large corporate farms, and they’re heavily capitalized with big investments into farm machinery… It’s not like the co-operative movement in the Saskatchewan politics of the CCF.”

The CCF is the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the party that became the NDP in 1961 under leader Tommy Douglas. It was originally a big-tent party for labour unions and farmers, leveraging shared discontent with economic and political elites and supporting both co-ops and credit unions. Despite its success in Saskatchewan, it never found a stronghold among Manitoba’s southern farm and rural communities.

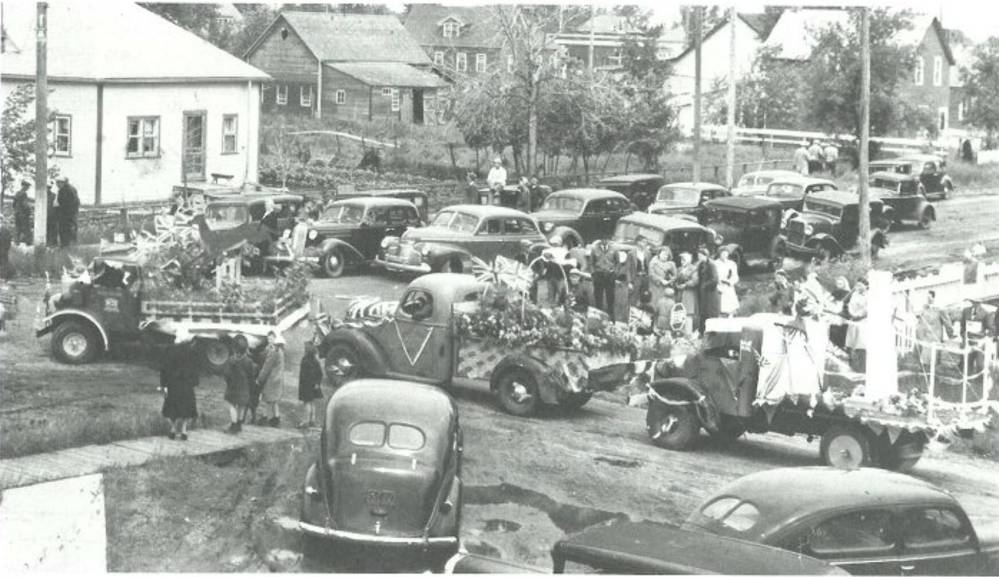

For his part, Winklerite J.M. Froese gravitated towards another party with populist associations: Social Credit. He represented the Rhineland riding as Manitoba’s sole Social Credit MLA between 1959 and 1973.

First established as the Alberta Social Credit Party (ASCP) in 1934, the Socreds were a Christian farmers’ party, strongest in Alberta, that confronted what they saw as predatory eastern Canadian bankers and the political elites serving them.

But, unlike the CCF, which they may seem to resemble, the Socreds weren’t left-wing critics of capitalism’s excesses. Political discourse in the 1930s supplied all too familiar scapegoats for anyone who wanted to decry “predatory bankers” for reasons other than being capitalist. ASCP founder William “Bible Bill” Aberhart developed this theme sharply in his radio sermons to Albertans, which blamed the Great Depression on communism and the Jews.

The ASCP later found a moderating influence in postwar leader Ernest Manning who served as Alberta’s premier from 1943-68. He kept the party’s anti-socialist and Christian emphasis but drummed out its antisemites and dropped its quirky monetary theories.

This was the spirit of the social credit movement when Froese — a devout Mennonite who advocated for lower taxes and opposed medicare as a compulsory program — delivered his first speech as a newly elected MLA in early 1960.

“I believe that extreme care must be exercised in avoiding destruction of the rights of the individual,” he announced, “which seems inevitable under the policy of centralizing.”

Froese’s “brand of populism,” as Werner explains, wed an emphasis on the rights of the individual with a view of the elite “as the people in Winnipeg who made laws and the people in Ottawa… (who) were outside of the community and threatened local control over things.”

This potent combination — where “the people” aren’t necessarily the poor or the working class, but more likely resilient farmers, entrepreneurs and contractors striving for freedom against meddlesome political elites and their cronies in capital cities — is obviously an old theme on the Prairies’ political right. And it’s one that’s continued to resonate over the decades, from Alberta PC premier Peter Lougheed’s rebellion against prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s National Energy Program and the Reform Party’s original rallying call to “Let the West In!” in the 1980s, to Saskatchewan Premier Scott Moe’s insistence a few years ago that “Saskatchewan needs to be nation within a nation” in defiance of the federal government’s interference and perceived revenue-draining policies, and the Freedom Convoy itself.

What power does this theme have now in Manitoba, that conflicted child of Eastern and Western Canada?

U of M historian Adams says Manitoba’s populism today is “anti-establishment… libertarian and it’s right-of-centre.” But he acknowledges this doesn’t mean it’s an overwhelming force. After all, Manitoba is the one Prairie province where the Conservatives still stand tall federally, a big-umbrella party for urban and rural conservatives alike. Unlike in Alberta and Saskatchewan, there are no effective parties further to the right here, at least not yet.

Meanwhile, Manitoba NDP Premier Wab Kinew — who “eschews left-wing populism,” writes the National Post approvingly — enjoys the highest approval rating of all Canadian premiers and governs from the centre-left. The CCF is seemingly a long way off in the party’s rearview mirror.

Manitoba appears to be an island of relative consensus. How much does plucky Portage-Lisgar stand apart?

Let’s return to the federal riding’s 2023 byelection.

Branden Leslie — a warm but sharp communicator, with farm roots south of Portage la Prairie — speaks frequently of defending “our rural way of life.” This means getting rid of the carbon tax, with its burden on farmers and producers who rely on propane and natural gas. It also means advocating for conservative values on issues like abortion — nothing out of the ordinary for the Prairie right. But his campaign also tapped into a larger zeitgeist. When he attacked Maxime Bernier’s authenticity, it wasn’t just because of his parachute campaigning. He circulated a flyer of Bernier wearing an LGBTTQ+ Pride T-shirt and criticized him for attending the World Economic Forum.

The WEF — the annual conference in Geneva that brings together a highly select group of business, political and academic leaders — is a lightning rod for attacks from the nationalist right.

Leslie’s message seemed clear: Bernier was a fair-weather rightist, content when it suited him to throw in with the “globalist Davos elites,” to borrow Poilievre’s decidedly populist lingo.

This may seem like a case of Leslie competing with the People’s Party leader over who’s the better populist. Nevertheless, Winkler’s former mayor Martin Harder is skeptical about using that label for someone like Leslie, whom he endorsed.

“(Populism) is a flash in the pan… if you hit the right button, you can get the majority of the people on your side for one term,” he says. “But if you look at the long term, you look at quality candidates, you look at somebody who has a better-rounded approach.”

The comment is a reminder that labelling someone a populist is hardly a neutral matter.

Perhaps there’s danger in throwing around the populist label too fast and loose as a way of caricaturing other Prairie conservatives and leftists. Couldn’t that perpetuate exactly what populists are accused of — intolerant “us-versus-them” thinking?

According to Gerald Friesen, a professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba who’s spent his career writing on western Canadian politics and history, the term “populism” obscures more than it reveals.

“This range of meanings (associated with populism) tells us that the term encapsulates a grievance, a cultural style and a campaign tactic,” he says. “Who is making the calculations about how to unite disparate groups under the banner of ‘the exploited’ or ‘the outsiders?’ Whose interests are being served when a political party fuels the people’s grievances? What will a new administration do?”

Canada may — as the Public Policy Forum and others report — be undergoing a period of polarization. It’s possible the country could see more watershed moments like the Freedom Convoy. Moments where there’s an almost overwhelming sense of disagreement between Canadians over basic rights and the rules of political fair play.

The term populism will no doubt continue to be used by many to make sense of the forces in Western Canada and elsewhere that stoke such polarization.

But none of this should mean that either populism or polarization are always threats to a liberal democracy.

Sometimes, they might represent messy, but still democratic, attempts to work through questions about what kind of Canadian liberalism we’re pursuing, touching on all the slippery meanings of “core values” like freedom, equality and pluralism.

A trip through the Pembina Valley can help to remind us of some of the winding paths by which Canadians have arrived at these values.

conrad.sweatman@freepress.mb.ca

Conrad Sweatman

Reporter

Conrad Sweatman is an arts reporter and feature writer. Before joining the Free Press full-time in 2024, he worked in the U.K. and Canadian cultural sectors, freelanced for outlets including The Walrus, VICE and Prairie Fire. Read more about Conrad.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.